Highlights

- For a typical family, the difference between the OBBB and our proposal is almost $500 per child. Most of those benefits flow to working-class and middle-income families. Post This

- Modest changes to the current legislative language in OBBB could generate large benefits for American families and fix the failure to keep family benefits on par with recent inflation. Post This

- Our proposed changes would reduce the number of families facing discrimination in the CDCTC from 60-70% to under 10%. Post This

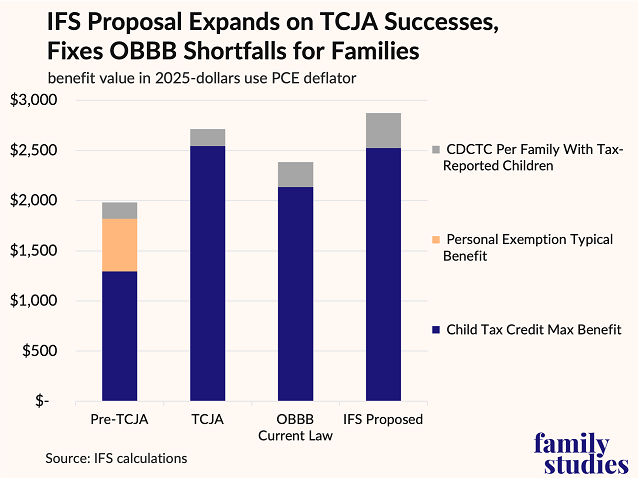

The “One Big, Beautiful Bill” (OBBB), enacted in July 2025, included numerous changes to child-related policies. Most notably, the Child Tax Credit (CTC) maximum benefit was increased from $2000 to $2200, that new value was indexed for inflation going forward, new “Trump Account” investments were established for children born 2025 and later, caps on employer-provided dependent care assistance were raised from $5,000 to $7,500, and the claimable percentage of expenses for the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC) was increased for many filers. Nonetheless, modest changes to the current legislative language could generate large benefits for American families and fix the failure to keep family benefits on par with recent inflation.

In a new policy brief released today, we outline three suggested changes to family policies in the OBBB that could appreciably strengthen and support American family life.

Suggested Changes to the OBBB

- The inflation-adjusted value of the 2017 CTC in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act should be restored by raising the CTC to $2,600.

- The phase-in of the CTC’s refundable value should begin at the first dollar of income, creating stronger work incentives for low-income families.

- The CDCTC’s eligibility rules should be changed to eliminate discrimination based on family status: one-earner families should be allowed to claim it, and generosity should scale with the third child rather than capping at the second child.

Taken together, these differences would result in the average American working family receiving $500 per child more per year—and ultimately getting slightly bigger benefits than they received under the TCJA.

The first two proposals are relatively straightforward. Increasing the CTC to $2,600 merely defends the real, inflation-adjusted value set in President Trump’s landmark 2017 legislation. Allowing the credit to phase in at the first dollar, rather than the 2,501st dollar, increases work incentives for currently nonworking families, as we have written previously. Both of these fixes to the CTC amount to slightly tweaking the CTC, mostly to protect its previously-established value and its intended purpose of supporting childrearing in working families.

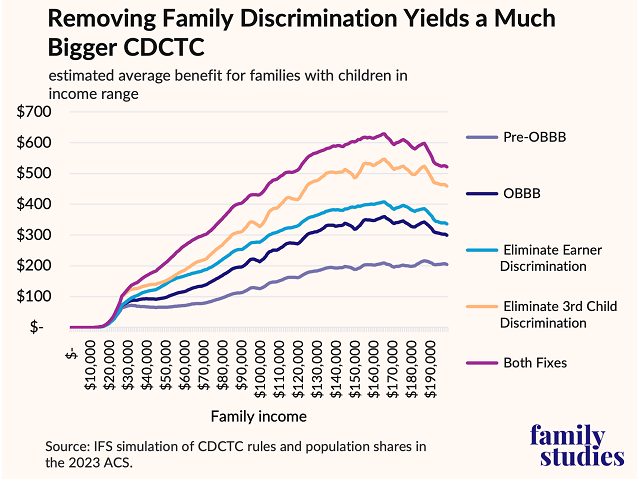

Our proposed fixes to the CDCTC are more complex. As it stands, the CDCTC discriminates against about 60-70% of American families with young children. The CDCTC does not allow two-parent, one-earner families to claim it at all, by calculating eligibility based on the lowest income of any spouse. Second, the CDCTC’s value doubles from the first child under age 13 to the second, but it does not increase again for third or higher children. Since many families do have three or more children under age 13, or have one nonworking spouse, huge shares of families are denied equivalent per-child benefits received by the lowest-poverty, two-worker, 1-or-2-children households. It is absurd to provide a working single parent with the CDCTC, but then deny that CDCTC to the same parent if he or she marries a nonworking spouse. Data from the National Survey of Early Childhood Education suggest that the 60-70% of families facing discrimination due to the current CDCTC average around $2,000 to $3,000 in what would otherwise be claimable expenses, so denying this credit is a substantial loss.

What is the effect of our proposed change to the CDCTC? The figure below uses data from the American Community Survey to simulate the average credit value families at each income level could get under various policy counterfactuals, based on their income, children, and other eligibility criteria, and assuming they have enough claimable expenses.

The OBBB already increased the generosity of the CDCTC, especially for higher-income families. Eliminating earner discrimination increases generosity by fairly similar amounts across the income spectrum, which means a bigger relative benefit for working-class families, though the nonrefundable nature of the credit curtails benefit for low-income families. Allowing the maximum benefit size to increase for third children mostly benefits richer families because poorer families hit the various caps in the CDCTC before third-child benefits fully phase in.

These changes would reduce the number of families facing discrimination in the CDCTC from 60-70% to under 10 percent. The CDCTC would change from being a narrow subsidy for a few higher-income families, to a broad-based child care subsidy available with equality to a vastly broader number of families, and these changes would push per-child family supports above their TCJA levels.

The fixes we have proposed pencil out to around $11-$25 billion in additional budgetary costs per year. This is a not a small sum in principle, but it is a drop in the bucket compared to federal revenues. We have sensible suggestions in the full brief on how the money could be raised without raising income taxes or cutting other family programs.

The benefits to families of these changes would be vast. For a typical family, the difference between the OBBB and our proposal is almost $500 per child. Most of those benefits flow to working-class and middle-income families, since the first-dollar phase in, one-earner discrimination fix, and third-child discrimination fix all disproportionately benefit these families. At a time when falling birth and marriage rates show that American families are clearly struggling, it is advantageous for Congress to at least ensure families get as good a deal as President Trump delivered for them in the TCJA. The OBBB did not fully deliver that. But with a few enhancements, Congress can.

Read the full IFS policy brief, Beyond OBBB: Three Fixes for American Families, here.