Introduction

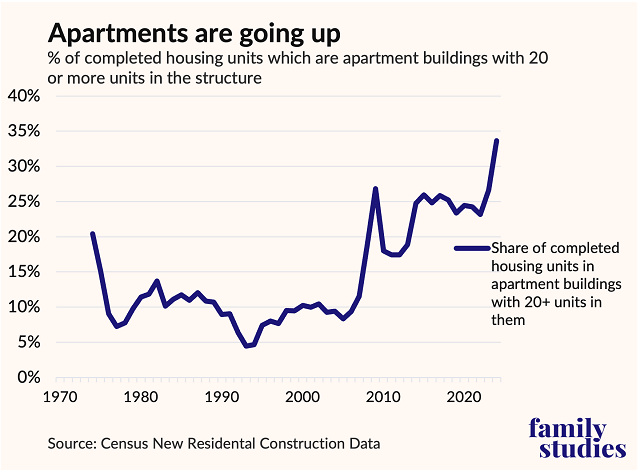

Since the Great Recession, there has been a massive change in the American housing market: more new housing is in the form of apartment buildings instead of single-family homes. In 2024, over one-third of new housing units were in buildings with 20 or more units; the first time since 1974 that such a high share has been reached.

If people want to live in apartments, that is their prerogative. But the rise in apartment construction is worrisome because prior IFS research has shown that very few Americans ideally want to live in apartments. More importantly, when most Americans think about starting a family, they overwhelmingly prefer not to live in an apartment. And yet, apartments keep being built. There are many reasons for this increase: delayed fertility and marriage have created a bigger market for small housing units; slower asset accumulation for younger generations has limited their housing options; apartment buildings yield more marketable floor area compared to the cost of land for developers; and the increasing bind of urban growth barriers and other limits to expansion have nudged developers to pursue more density inside cities rather than building entire new neighborhoods.

These factors are not going to disappear overnight. At the city, state, and federal levels, bi-partisan politicians are passing bills with the specific intent to open up more land for apartments. Multiple cities have passed laws eliminating parking minimums. The states of Texas and California have both passed multiple laws this year to specifically open up more land to build apartment buildings. The “One Big Beautiful Bill” included a re-authorization and expansion of the Opportunity Zone program, which only funds the construction of rental housing and predominantly includes apartments.

As a result, we should expect apartment construction to be a significant, if not an increasing, percentage of new US housing stock. As such, for those who care about helping American families reach their fertility goals, it’s important to ask: could we make this wave of apartment construction more family friendly? Although we know that Americans generally do not prefer apartments when it comes to family life, are there some apartment designs that are less obstructive to family formation? What about apartments for specific types of families, like a newlywed couple living in their first home together? Or what about a family with only one child?

To answer these questions, we fielded a survey of over 6,000 Americans ages 18 to 54, providing them with a range of questions about family and housing, and asking them to rate specific buildable floorplans, architectural renderings, and apartment building amenities. What we found is striking: among apartments with a similar square footage, some apartment layouts are systematically better for family life than others. More open floorplans with fewer rooms per square footage had lower ratings from Americans interested in starting a family than identical-square-footage apartments with more division into rooms, and those ratings translate into a willingness to pay higher rent for more bedrooms.

Family-friendly apartments are in short supply around the country, not least because almost none are being built. But we do not believe this is due to market efficiencies: family-friendly apartments have low vacancy rates, pointing to high demand, low turnover, and an undersupply that may arguably come from a mixture of regulatory barriers and genuine market perception failure among builders and investors. The takeaway is clear: if obstacles to family-friendly apartments can be removed, more such apartments will be built, and as a result, more young couples could have their first or second child earlier in life, raising fertility rates nationwide. Besides changes in private-sector practices, policymakers could especially consider ensuring that parking rules are per-unit rather than per-bedroom, and that public housing trusts have a mandate to produce family-friendly units.

Key Findings

- People who live in small apartments are less likely to have children. Building more family-friendly apartments would likely increase birth rates for young Americans.

- Apartments are a growing share of new housing but are getting less family friendly: smaller, with fewer bedrooms.

- Americans are willing to pay more per square foot for an apartment with more bedrooms, and these units with more bedrooms are strongly associated with more openness to having children.

- Family-friendly units are more cost-effective than developers and investors realize. One reason these units are underprovided is that developers use erroneous assumptions about vacancy rates that ignore the fact that smaller units have higher vacancy rates, higher turnover, and higher rates of budget-constrained residents who may miss payments.

- Exempting family-friendly units from floor area ratios, setting parking requirements per-unit instead of per-bedroom, accelerating permitting time for small projects, mandating that public housing trusts provide family-friendly units, and expanding Opportunity Zone-like rules for development could all increase the number of family-friendly apartments on the market.

The Rise of Apartments

There has been an explosion in apartment and condominium construction in recent years. The figure below shows the share of new housing units in America that are in apartment buildings with 20 or more units. After the subprime mortgage collapse of 2007-2008, apartments rocketed upwards as a share of home construction.

Figure 1. Share of completed housing units that are apartment buildings with 20+ units

The main reason for this was that single-family housing construction cratered. In 2006, 1.65 million single-family homes were completed, according to Census Bureau data. In 2009, just 520,000 were. But it was not only a decline in single-family homes. In 2006, 185,000 apartments in large buildings were completed. In 2009, 213,000 were completed. By 2019, there were 293,000 apartments finished even as single-family housing completions remained below a million. In 2024, 548,000 apartments were completed in large buildings, while single-family completions languished at just a million.

This boom in apartment construction has many sources beyond the scope of this paper, and it is not our goal to disparage or discourage apartment living or apartment building. Both authors of this brief started their families while living in apartments in big cities, and one of the authors (Bobby) has spent his career as a developer putting up apartment buildings during the very wave of construction we are discussing here.

But in the long run, the American people don’t want to raise their families in apartments. Prior research by the Institute for Family Studies found that about two-thirds of people in every state prefer detached single-family homes, and most of the remainder prefer townhouses or other options, not apartments. We also found that when it comes to raising a family, Americans reject apartments (vs. single-family homes) almost as much as they reject the idea of an extra hour of commuting, or hundreds of dollars of housing cost increases.

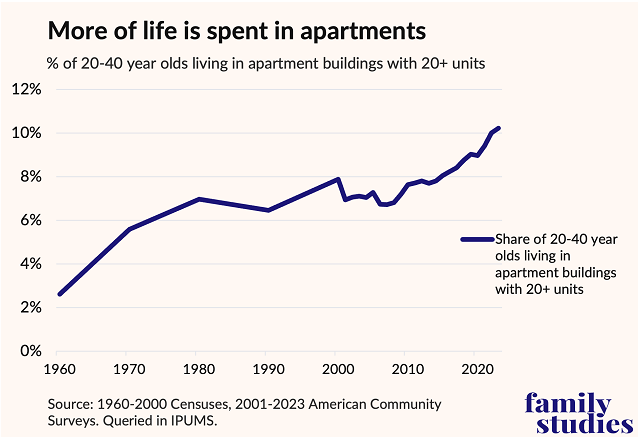

Thus, the future for American families will not be found in widespread apartment construction. Even so, young Americans are spending more of their lives in apartments. Whereas in 1960, under 3% of Americans ages 20 to 40 lived in apartments, today that share is over 10 percent. The huge runup is fairly recent, occurring mostly since 2010.

Figure 2. Share of 20- to 40-year-olds living in apartment buildings with 20+ units

Given that Americans are spending more of their prime years for family formation living in apartments, even though most Americans don’t envision raising a family in an apartment in the long run, it is important to make apartments as family friendly as possible. The fact is that large shares of Americans will spend their young adult years in an apartment, and maybe even get married while living in one, and may still be in an apartment when they have their first child. And since apartments are a large share of new construction, a lot of young Americans ultimately have no other option: either an apartment—or mom and dad’s basement.

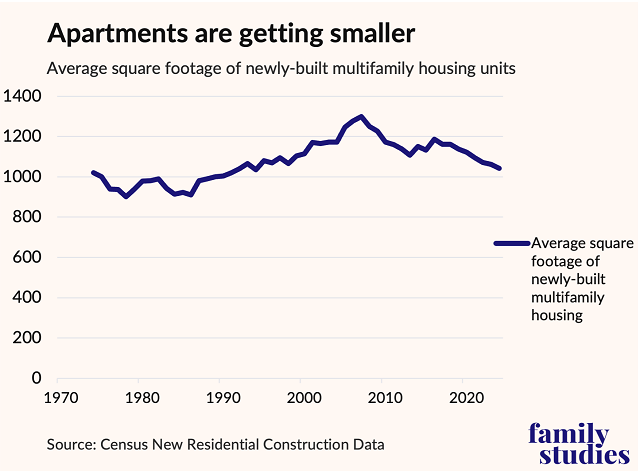

Apartments are also getting smaller over time and less suitable for families. Sizes of new multifamily housing peaked in 2007 at 1,300 square feet on average—a figure which has fallen to 1,043 as of 2024, a 20% decline in under 20 years.

Figure 3. Average square footage of newly-built apartments

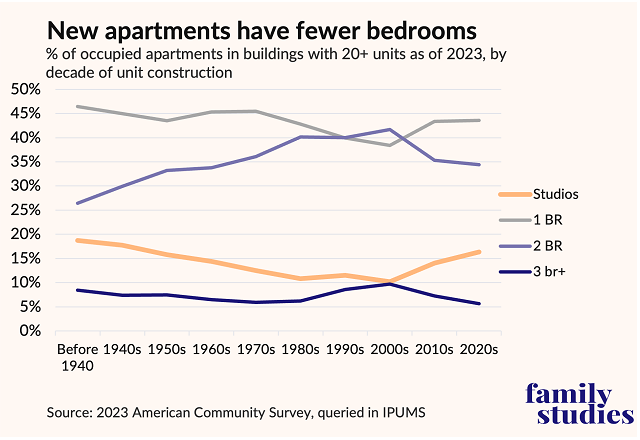

The number of bedrooms in new apartments has fallen as well. Apartments built since the 2010s are far likelier to be studios and one-bedrooms than two+ bedroom units that are more suitable for family life. Whereas three+ bedroom units represented 7-11% of construction in the 1990s and 2000s, they are just 5% today. On the other hand, studio apartments were just 10-12% of construction in the 1990s and 2000s, but account for over 15% today. There has been a similar shift away from two-bedroom units in favor of one-bedroom units.

Thus, there is an ongoing seismic shift in American housing. Apartment-dwelling for younger Americans has continued to increase, even as the apartments they live in have gotten smaller. Moreover, a growing share of that reduced square footage is devoted, not to common areas, dens, or offices, but bathrooms—the ratio of bathrooms to bedrooms in apartments is rising steadily over time. As a result, young Americans today are vastly more likely to be living in housing environments they themselves see as unsuitable for family formation, and probably designed for roommates rather than a family, according to their own survey responses.

Figure 4. Share of occupied apartments in buildings with 20+ units as of 2023, by decade of unit construction

Previous work at IFS outlined how America could unleash more construction of the starter-homes young families need. But in the meantime, apartments are still going to be built. This report explores how to make those apartments more family friendly and specifically explores whether there is any reason to think young Americans would actually pay the rent on family-friendly apartments. While there may be hard-to-change economic reasons why apartment construction is booming, it seems reasonable to think that the average size of new apartments could be nudged back upwards, or that bedrooms-per-unit could be pushed back nearer 1.5 vs. the current 1.3. These changes would help more young families get started having that first child, even if they may still eventually move to a single-family home as their kids get older.

Data & Methods

In May 2025, the Institute for Family Studies, in partnership with Demographic Intelligence, completed the Multifamily Housing Survey of 6,288 Americans ages 18 to 54 on the survey platform Alchemer.

We aimed to sample 6,000 respondents; ultimately, to achieve specified quotas for representativeness by age and marital status, 6,288 completed responses were collected. To get these 6,288 completions, 13,200 respondents were recruited to begin the survey. Of these, 5,660 were disqualified due to age, geography, or failure of basic attentional screeners. An additional 1,236 failed to complete the survey. Finally, 738 completions were disqualified due to failing speed checks or checks for straight lining of responses. Of the remaining 6,288 responses, 5,117 passed all quality-control benchmarks related to illogical question responses, response timing, and open-text responses, per quality-control advice articulated by the Pew Research Center. Respondents were sampled to ensure approximate representativeness for the United States population by age, sex, and marital status. Respondents were then weighted by age, sex, race, marital status, number of children in the home, geographic region, employment status, and education, to ensure a close fit to the April 2024 Annual Social and Economic Supplement to the Current Population Survey.

Within the survey, respondents faced several questions asking them to identify which of several apartment floorplans they preferred. Apartment floorplans and 3-D renders were provided by The American Housing Corporation.

Houses Americans Value

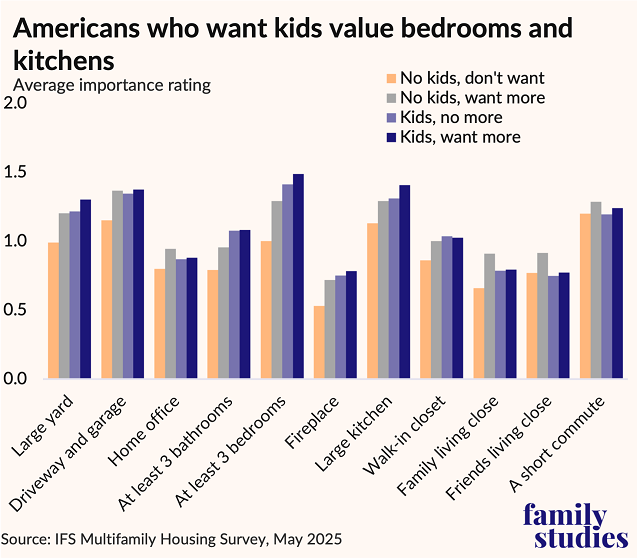

Different people naturally want different things from a house. We started out by simply asking respondents if a range of features of a house were “Very important,” “Somewhat important,” or “Not important,” and then we converted these answers to an index from 0 (not important) to 2 (very important). This gives us a baseline of what people want. We then segmented those responses into four groups by parenting status: childless people who don’t want any kids, childless people who want kids, people with kids who don’t want any more, and people with kids who want more. This figure shows how valuations of specific features varied across parenting status.

Figure 5. Average importance ranking of household trait

For some features, there are not big differences across groups: all groups placed a fairly low value on home offices and proximity to family or friends. Likewise, all groups valued a short commute. But for some features, there are large differences. The most important feature for families with kids is that a house has at least three bedrooms. For childless respondents who do not want kids, the most important feature is a short commute. In general, the biggest gaps are observed for bedrooms, yard size, bathrooms, kitchen size, fireplaces, and walk-in closet space. This all makes sense—families need space.

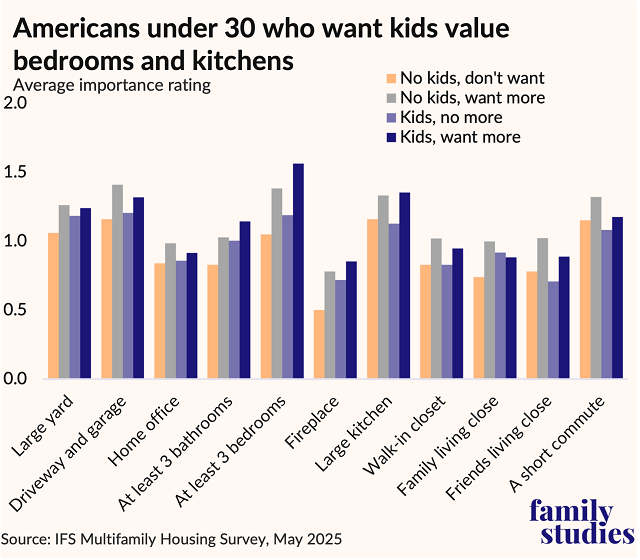

However, it is worth asking if this is true for young Americans. Maybe younger generations have different values and therefore do not really care about the same things. The figure below shows the same figures, but now just for Americans under age 30.

Figure 6. Average importance ranking of household trait for respondents under 30

When it comes to younger Americans, the gaps seem just as large. Those who want more kids value bedrooms, large kitchens, more bathrooms, and fireplaces. This all supports the notion that the decline in apartment size and bedroom count probably matters a lot for shaping family life.

How Americans Rank Apartments

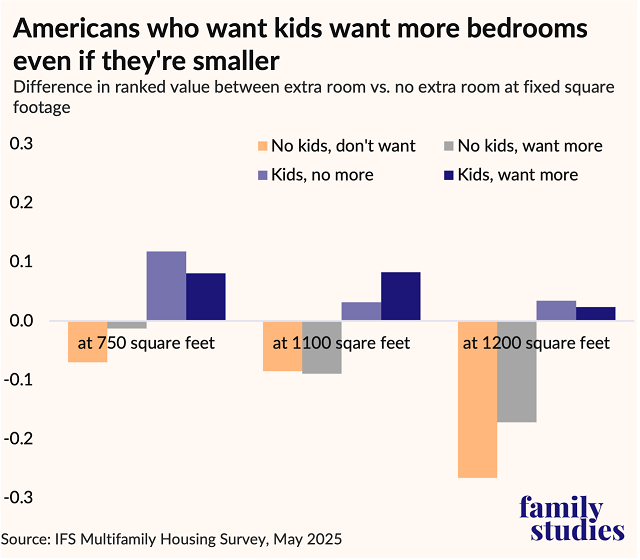

To better understand how Americans think about starting a family in an apartment, we provided them with a range of comparisons of apartments. To begin with, respondents were given six apartments to rank: two were 750 square feet, two were 1,100 square feet, and two were 1,200 square feet. Within each size band, apartments varied by number of rooms: one bedroom with a large common area vs. one bedroom with a normal common area, and a separate den at 750 square feet; two bedrooms and large common area vs. two bedrooms and a spare den at 1,100 square feet; and two bedrooms vs. three bedrooms at 1,200 square feet. Respondents also saw floorplans of the six apartments to help them visualize the choice.

We then asked respondents to rank the six apartments from the one that would make them feel most comfortable having a(nother) child, to the one that would make them least comfortable. For each of the four parenting categories, we were interested in how they would rate subdividing the fixed square footage into more rooms. Do most people want a few rooms and a big open layout? Or is slicing an apartment up into more bedrooms better?

The figure below shows the difference in average rating (1-6) between the “extra room” version of each apartment size vs. the “no extra room” version.

Figure 7. Difference in ranked value between extra room vs. no extra room

In every case, the “no kids, don’t want” respondents have a clear preference for the more open layout. Yet also in every case, people with kids have a clear preference for more bedrooms.

The fact that people who do not have kids but want them do not have such a preference probably attests to two facts: first, the base case of a two-bedroom apartment at 1,100 or 1,200 square feet probably is enough for many people to feel confident having a first baby; second, once you actually have kids, you may realize they take up more space than you realized, or that you’d really like another bedroom for family to come and visit and help with your child. Regardless, it is clear that the shift towards more open apartment layouts is uniquely tailored for the interests of childless people who don’t want kids.

Floorplans Americans Choose

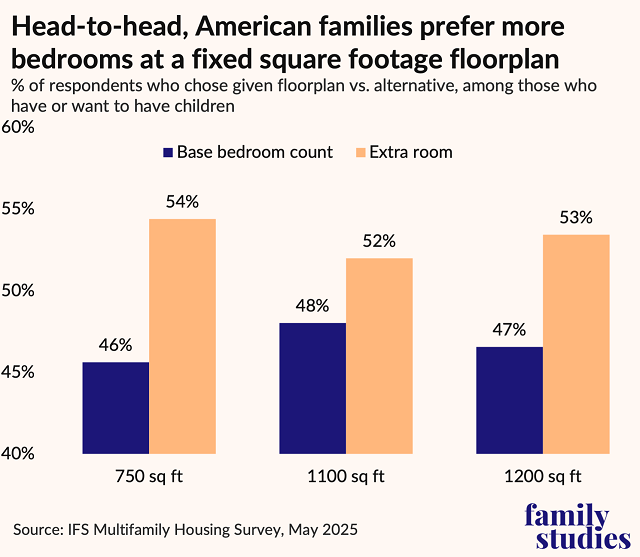

Ranking a lot of options, however, may not be the best way to capture preferences, especially since it’s hard for respondents to keep a mental picture of six different apartments at once. So, to further illuminate differences, we next showed each respondent a random pair of two floor plans alongside a furnished rendering of the common area of the apartment. All apartment renders had similar furnishings and lighting to the extent possible. Respondents were asked to rate which of the two apartments would make them feel most confident about having a(nother) baby. The next figure shows the relative “win percentages” for each apartment pairing, among respondents who ever wanted any (more) children.

For simplicity, we show just the head-to-head selection rates for apartments of the same square footage. When asked to choose between a 750 square foot unit with one bedroom vs. a bedroom and a separated den, 47% chose the one-bedroom, while 53% chose the room with the den. These effects are not enormous, but their persistence across unit sizes, and the fact that these effects are observed even in a survey question where we did not explicitly highlight that units varied only on bedroom count suggest that Americans interested in having children really do want and need more rooms, not just more square footage.

Figure 8. Share of respondents who chose given floorplan and apartment render vs. alternative

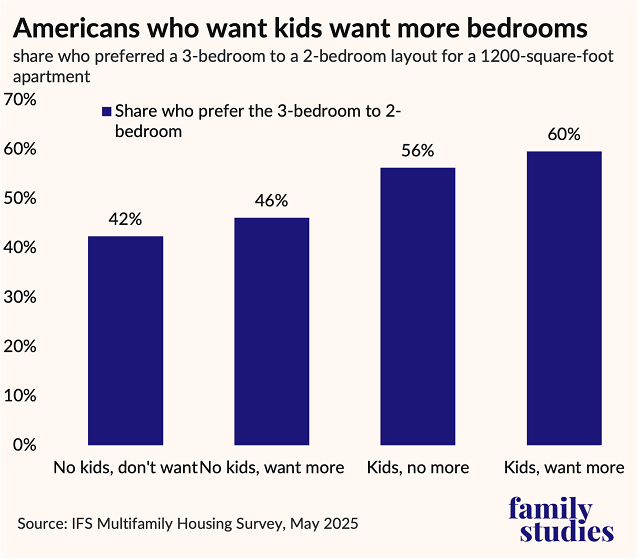

Focusing just on the 1,200-square-foot apartment comparison, it’s worth seeing how preferences shake out by parenting status: preferences for more bedrooms scale directly with actual or desired family size. Among the childless, there is a net preference for fewer bedrooms—but among those who have children, there is a net preference for more bedrooms. Bedroom counts simply are the sine qua non of family-friendly housing.

Figure 9. Share of each parenting status group who preferred a 3-bedroom over a 2-bedroom layout for a 1200-square-foot apartment

Tradeoffs Americans Will Make

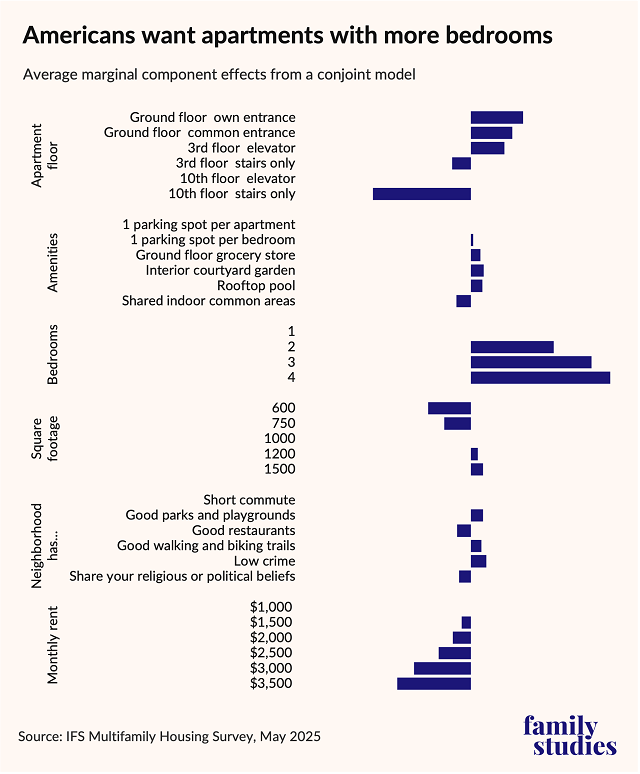

It’s clear that Americans value more bedrooms in apartments: but will they pay for it? What tradeoffs will Americans actually make? To assess this, we used a conjoint framework, where respondents were asked to choose between two different apartments and select the one that would make them feel more confident in having a(nother) child.

But in this case, the apartments varied across several traits: apartments were randomly assigned a floor/degree of access, a number of bedrooms, a square footage, a monthly rent, a description of neighborhood amenities, and a description of apartment building amenities. The next figure essentially presents the extent to which seeing a given trait altered the odds that respondents selected the apartment scenario containing that trait value. Positive values indicate that a trait was appealing to respondents; negative values show that it was unappealing.

By far, the most important feature of an apartment is the number of bedrooms in a unit. The difference between two and four bedrooms is about as influential for respondents in their apartment selection as a difference of 600-900 square feet or an extra $1,500 in monthly rent.

The way conjoint surveys work, this does not literally mean that respondents would pay $1,500 more for two extra bedrooms: they may not have that much money available. Rather, it means that at a given budget constraint, extra bedrooms would give them as much expected value as that kind of change in rent.

Other features matter too, of course. Respondents vigorously reject 10th-floor walkups, for obvious reasons. They also prefer ground-floor units. Plenty of other features of the neighborhood matter, but nothing matters quite like bedrooms. The fact that bedrooms matter so much more than square footage is consistent with the previous results: at a given square footage, Americans would prefer more bedrooms. There is more variance in bedroom count preferences than square footage preferences.

Figure 10. Conjoint survey results on apartment preferences, all respondents

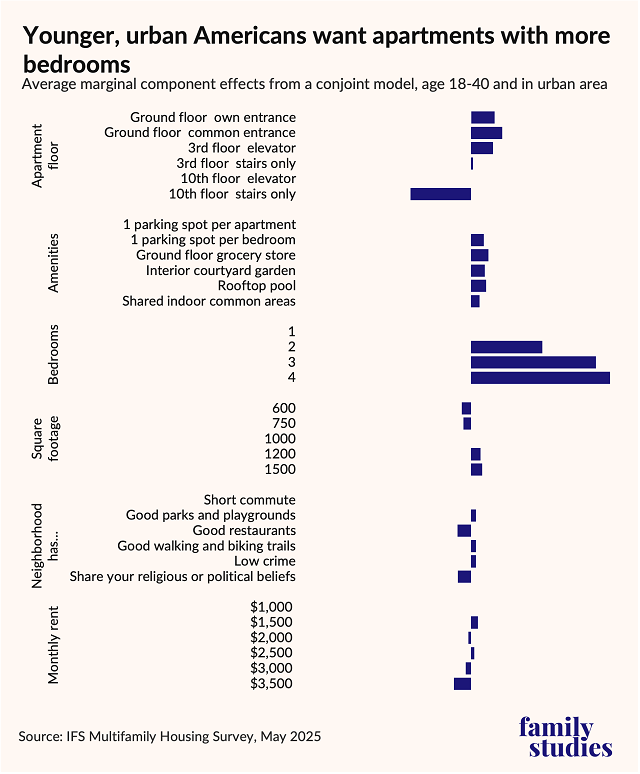

But, of course, apartment builders are not marketing apartments to “Americans generally.” Below, we re-estimate the same conjoint model, but this time, we limit it to Americans under age 40 who reported living in urban areas.

Figure 11. Conjoint survey results on apartment preferences, urban respondents under 40

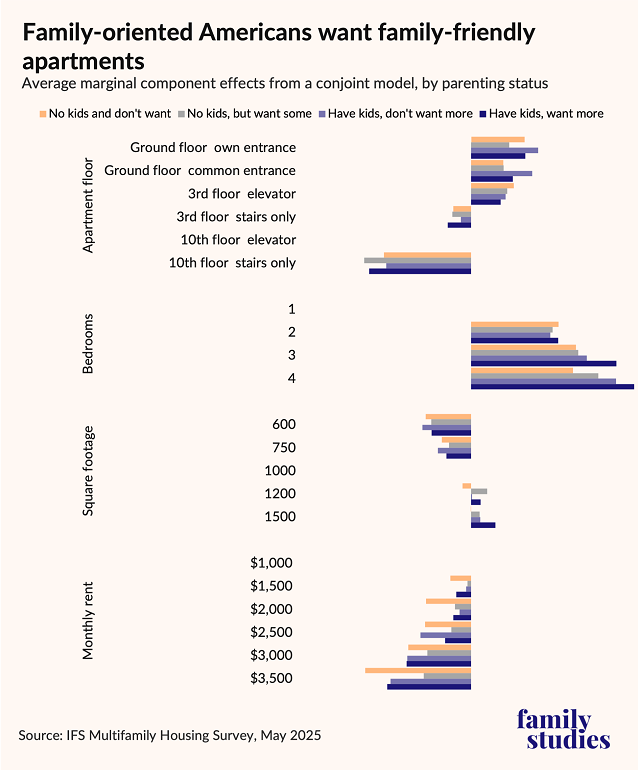

Next, we compare how a willingness to make tradeoffs varies across the parenting statuses used throughout this report. For ease of reading and because effect sizes are small, we do not present results for apartment amenities and neighborhood traits in the figure below.

Figure 12. Conjoint survey results on apartment preferences, by parenting status

The exact same pattern is clear: bedrooms are more salient than virtually any other feature of an apartment, even for younger, more urban respondents who are the target market.

By and large, across parenting statuses, Americans have similar pricing constraints, preferences around building access, and square footage preferences. But when it comes to bedrooms, there are large differences. For the childless-by-choice, there is little difference between two, three, or four bedrooms. But for those with children who want more, there is an enormous difference: more bedrooms make all the difference.

Family-Friendly Apartments Are In Demand

The survey evidence shows that there is enormous pent-up demand for family-friendly apartments, yet apartments keep getting smaller. On its face, this would seem to point to a gap between individuals’ “stated” and actual “revealed” preferences. Perhaps people say they want bigger apartments, but they do not want them in reality.

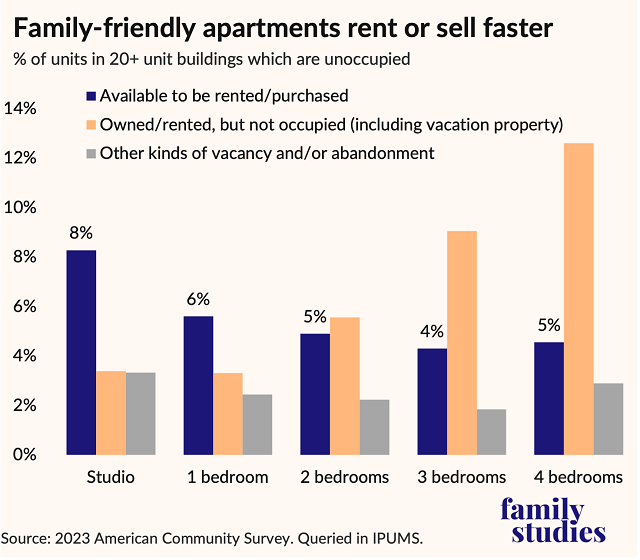

However, the data on apartment demand confirms that units with more bedrooms are indeed in high demand. The American Community Survey provides data on the vacancy status of housing units. In the figure below, we show, among apartments in buildings with 20 or more units, what share of those units are vacant, by the type of vacancy and number of bedrooms.

For property managers, builders, or landlords, the most important kind of vacancy is the bar in dark blue: units which, in principle, could be rented or purchased, but have not been. That kind of vacancy accounts for about 8% of studio apartments, but only 4 to 5% of three- and four-bedroom apartments. Much of this vacancy is a result of smaller units having greater turnover. Since it is uncommon for leases to end and then begin on the same day, this results in an increase in the vacancy percentage.

Figure 13. Vacancy rates by bedroom count in apartments in buildings with 20+ units

Some three- or four-bedroom apartments are indeed unoccupied, but their rent is still being paid—these larger vacant apartments tend to be seasonal use for snowbirds, vacation properties, beach condos for rental, timeshares, or units under contract but not yet occupied. As far as a builder is concerned, that kind of vacancy is no problem, since the unit is being paid for. But it should be noted that for society on the whole, large numbers of seasonally vacant units that could house families may not be a highly desirable outcome. Other vacancies, largely due to property abandonment, are similar across unit types.

Two facts immediately emerge from the figure. First, it really is the case that family-friendly units are in demand. Vacancy rates for these units are about 40% lower than for studio apartments, and about 20% lower than one-bedroom apartments. Because vacancies are lost money for landlords, that means that smaller apartments would need to rent for appreciably more per square foot to compete with family-sized apartments. Increased turnover leading to vacancy also meaningfully increases the operating expenses of the property: carpets are replaced, walls are repainted, and marketing dollars and staff time are spent on finding new tenants.

The second fact that emerges is that many family-sized apartments are sitting unoccupied. But rather than proving these units are not in demand, this actually shows that these units are in demand: the fact that nearly 13% of four-bedroom apartments in America have absentee residents paying rent, of which 7% are specifically for vacation usage, tells us that these units are so valuable that people will buy or rent them—even if they can’t actually live in them. For many people, “vacation” ends up meaning a three- or four-bedroom apartment (perhaps by a beach or near the ski slopes)—and yet these clearly highly desirable units are rarely built for living. Again, it should be noted that “seasonal use vacancy” is not a vacancy at all from a builder’s perspective: seasonal use vacancies still pay rent. Instead, seasonal use vacancies reveal what kind of apartments people see as highly desirable. And those seasonal use vacancies are overwhelmingly big apartments.

Do Family-Friendly Apartments Boost Fertility?

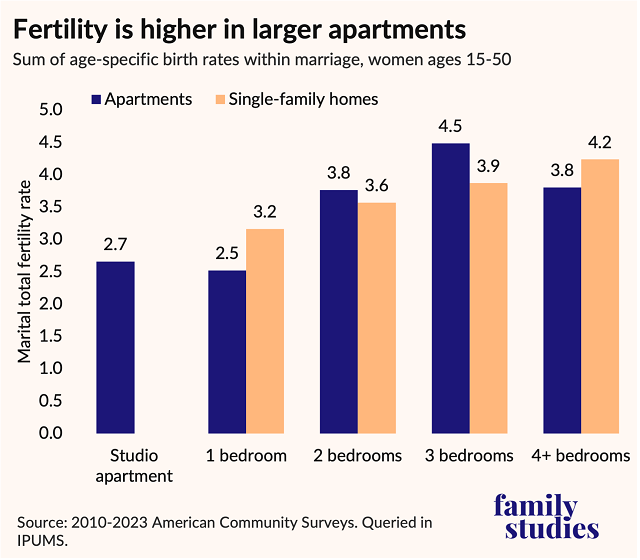

Finally, it must be asked: are fertility rates higher when families have access to larger apartments? The figure below, showing marital total fertility rates (to control for the fact that women in small apartments might simply not be partnered), answers that question in the affirmative. While fertility rates are low for married women in smaller apartments, they are high in larger apartments—in fact, married women in two- or three-bedroom apartments have somewhat higher birth rates than married women in two- or three-bedroom single-family homes.

Figure 14. Marital total fertility rates for U.S. apartment-residing women by bedroom count

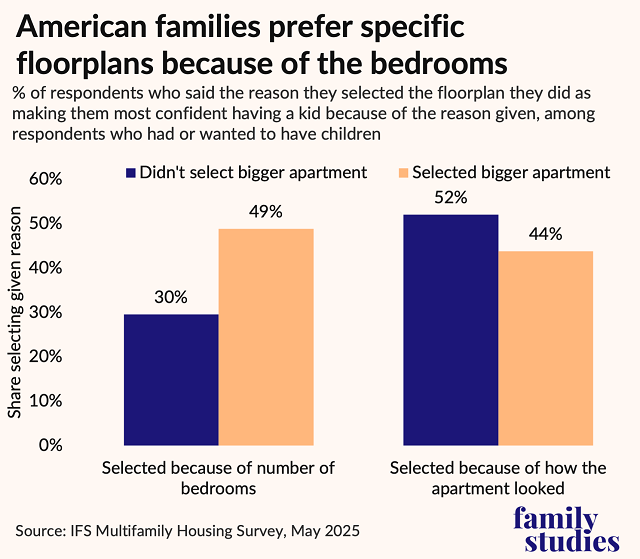

Moreover, when we asked respondents in the survey to select the floorplan images that would make them feel most confident having another child, we also asked why they selected those images. Of respondents who selected the apartment floorplan with more bedrooms, the figure below shows the reasons they reported.

Figure 15. Share of respondents who said the reason they selected the floorplan they identified as making them most confident having a(nother) child because of the reason given, by apartment size selection, among respondents who have or want to have children

Among family-minded respondents who prefer the floorplan with more bedrooms, almost 50% say that the additional bedrooms are in fact the reason they selected that floorplan. Our respondents explicitly identified higher-bedroom-count apartments as making them likelier to have children and then re-affirmed in a follow-up question that the bedroom counts were the motivating factor for their apartment-floorplan selection.

Respondents who chose the lower-bedroom-count floorplans are far less likely to say bedroom counts were their motivation. On the other hand, lower-bedroom-count floorplans overperformed in respondents’ aesthetic judgments, probably because their common spaces were larger, and the images provided to respondents focused on common spaces.

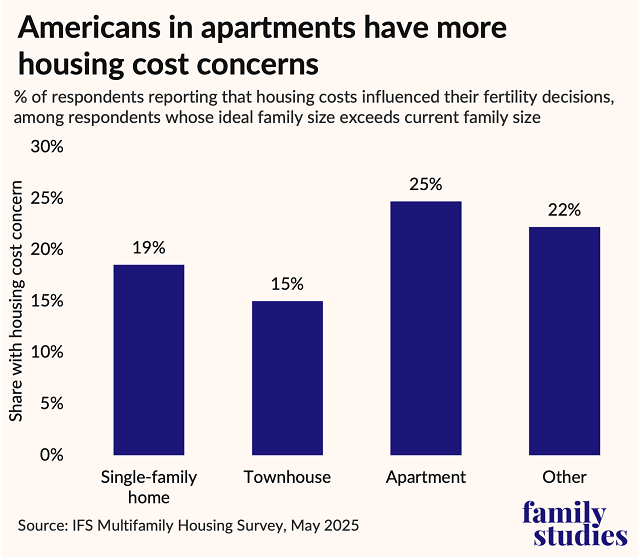

Moreover, while our survey did not ask respondents about the number of bedrooms in their current home, we did ask the kind of home they live in. We also asked if housing costs had recently influenced their fertility decisions. The figure below shows the share of respondents who said housing had influenced their family plans, among respondents whose ideal family size exceeded their current child numbers (i.e., among respondents who might be considering more children).

Figure 16. Share of respondents reporting that housing costs influenced their fertility decisions, among respondents whose ideal family size exceeds current family size

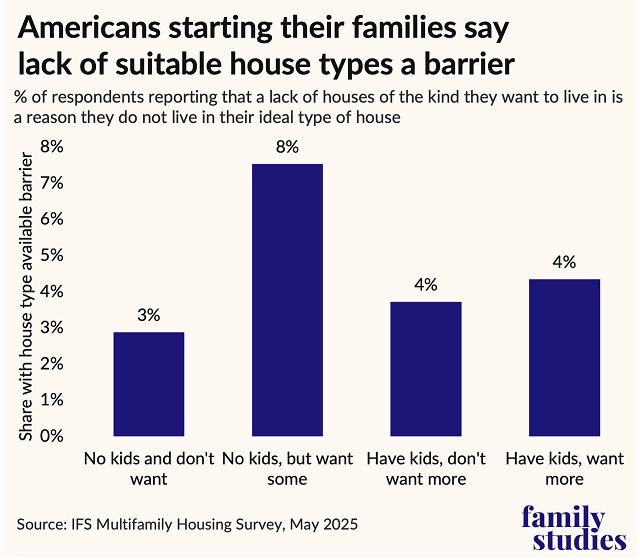

And finally, we asked respondents about the ideal type of home they would prefer. Then, among those who did not yet live in their ideal home (mostly respondents living in apartments), we asked why that gap exists. The figure below shows that Americans not living in their ideal home type are uniquely likely to say the reason for this gap is a lack of suitable home options if they are childless but want kids. Lack of diversity in home types is a particular barrier to people just starting out on family life: these people disproportionately need modest starter homes, as we have previously written, or, failing that, more family-friendly apartments.

Figure 17. Share of respondents reporting that a lack of houses of the kind they want to live in is a reason they do not live in their ideal type of house, by parenting status

Fertility rates are low for couples who live in small apartments—but not for couples who live in family-friendly apartments. That correlation probably isn’t spurious: across numerous question types, our respondents repeatedly articulated that more bedrooms would make them more willing to have desired children, and respondents in predominantly small apartments are far more likely to report housing-related constraints on fertility. There may be many reasons for this, but the obvious jump in birth rates at two-bedrooms strongly suggests that the main driver is simply the desire for a child to have their own nursery or room, a desire that is widespread in American society.

Therefore, the dearth of family-friendly apartments amidst a massive boom in apartment construction is a significant headwind for American family formation. If builders built more family-sized apartments, it is very likely that more Americans would have children.

Why Haven’t Developers Delivered More Family-Friendly Apartments?

As shown above, new supply of family-sized apartments has not kept up with the wider apartment boom: just 5% of recent apartment construction is for three+ bedroom units, versus over 15% for studio apartments. This presents a conundrum: if family-sized units are as in demand as these findings suggest, why aren’t developers building them?

One key reason is that large-scale housing investments represent a uniquely cautious industry focused on delivering risk-adjusted returns. These projects are almost always financed by investors who want a demonstration that units are leasable and can achieve a market rent. Builders can save on design and construction costs by building the same or similar structures multiple times across multiple projects, and investors can see that similar projects are widely available for comparison elsewhere to establish expectations about rents.

This being the case, builders, buyers, and lenders all have strong incentives to repeatedly build highly similar projects and, in particular, to repeatedly build any kind of structure that has already been shown to satisfy common building code rules and deliver minimally satisfactory profits. That a different building design might increase profits 1% is less important to developers than the fact that an untested building design could result in a massive, virtually unrecoverable loss.

Construction of speculative new configurations of units would, therefore, be confined to small structures—but very few small apartment structures are actually built. Of the 4.5 million occupied, rented apartment units built since 2010 in buildings with five or more units and estimated in the 2023 American Community Survey, 51% were in buildings with 50 or more units, and another 19% in buildings with 20 to 49 units. Moreover, even if buildings have under 50 units, a housing development may have multiple buildings: a recent report suggested that the average apartment-building project has over 230 units.

Apartment developments tend to be large investments, and thus unsuitable for risky bets on new housing configurations. Developments may require hundreds of units or more to procure cost-competitive insurance, and a single site may need well over 100 and as much as 200 units for an on-site property manager to be cost-effective. Large institutional investors may prefer not to purchase large numbers of small ($5-$30 million) apartment buildings due to the costs associated with managing numerous properties, and thus small projects can be starved of investors.

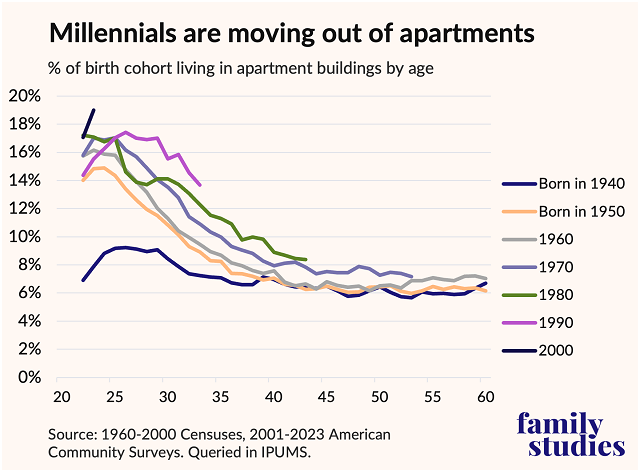

Finally, developers and investors are mostly backward-looking in terms of demographics rather than forward-looking. Enormous investments in apartment-style housing have been based on the assumption that younger generations prefer to live in apartments. Yet, apartment-dwelling is a life-cycle phenomenon, and the large “Millennial” cohort born around 1980-1990 is now aging out of its likely years of peak apartment-dwelling.

The figure below shows, for individuals born in the given year, what share lived in apartments at their various ages.

Figure 18. Share of birth cohort living in buildings with 10+ units by age

Developers have rightly sensed growing demand for apartments—but are likely not correctly anticipating the incoming life-cycle effect. As birth rates fall, each cohort is smaller, and thus while each cohort may have greater preference for apartments, that preference will increasingly be offset by larger, older cohorts aging out of peak-apartment ages. Apartment developments will likely face oversupply and vacancy issues within the next decade due to these effects, especially apartment developments that are incompatible with the life cycle factors that drive this dynamic: marriage and childbearing. In fact, family-friendly apartments really are less sensitive to these life cycle effects: whereas people in three+ bedroom units represent under 10% of all apartment-dwellers ages 25-34, they represent almost 15% of 40-year-olds. As apartment-dwellers age, they need more bedrooms for their kids, and as such, family-friendly units are better positioned to absorb ongoing cohort changes than other units. Failure to account for this ongoing demographic change likely accounts for some undersupply of family-friendly units.

Thus, the market segment (known as the “Missing Middle”), which might be expected to innovate in providing more family-friendly housing, simply does not operate at a scale to provide much housing at all. Infamously, the construction industry has seen a decline in the marginal productivity per worker over the past half century, due to increased regulations, and a lack of technological innovation relative to other industries. This effect is magnified in smaller projects where even the builder’s administrative efficiencies vanish. Despite the fragmentation of the housing development industry, each individual player in it operates at a scale and with a risk-management strategy that makes it hard to justify building anything other than the kinds of buildings that have been built a thousand times already.

Why Don’t Developers Add Family Units to Large Developments?

The second main reason family friendly units are not being built relates to why they represent such a low share of even larger projects. Developers could add a few more three-bedroom units in large projects yet often do not. Why?

To begin, smaller apartments do command a higher contract rent per square foot, and builders anticipate selling the development at a calculation conducted per rentable square foot. While smaller apartments can be more expensive to construct per square foot due to higher prevalence of bathrooms and kitchens, the reality is that land, overhead, planning, financing, and regulatory costs are such an enormous share of apartment construction costs that this kind of variance might not change cost factors as much as might be expected. Moreover, whereas in the past, a three-bedroom apartment might have just one bathroom, today even many families who want to rent a three-bedroom unit may prefer two or even three bathrooms. Thus, builders and managers buy and sell apartment buildings at rent-per-square foot.

In most cases, buildings are priced and sold on fairly conventional assumptions about vacancy rates, rates of rental nonpayment, and costs to find tenants. Individual builders and property managers may vary in their assumptions, but industry experts suggest that builders and managers do not generally assume that vacancy rates and credit collection losses systematically or dramatically vary by bedroom count. Yet as we showed above, vacancy rates do vary across bedroom types. Smaller units spend more time unrented: studios spend 12% of their time unowned and unrented, one-bedrooms 8%, two-bedrooms 7%, and three-bedrooms 6%.

But it turns out that payment risks vary, too. Residents of studio apartments pay an average of 32% of their income in rents vs. 25-26% for residents of larger apartments. Moreover, tenant tenure varies: in the 2023 ACS—again just looking at units rented in large apartment buildings and built since 2010—the average tenant had lived in their unit for 23.5 months for studio apartments vs. 29.2 months for three-bedroom apartments. All of this adds up to very real cost differences as buildings with more studio and one-bedroom units will have more vacant time without rent being paid, more costs repainting and relisting apartments due to turnover, and a larger share of tenants missing their rent because they are budget-constrained. Buildings full of small apartments are more expensive to operate.

To demonstrate this, we calculated effective rents for different bedroom counts using realistic data. In July 2025, Zillow estimated that asking rates were $1,429 for an average studio apartment, $1,333 for a one-bedroom, $1,555 for a two-bedroom, and $1,976 for a three-bedroom. In 2023, the ACS found values of $1,795, $1,800, $2,172, and $2,139, respectively. Thus, according to Zillow, three-bedroom apartments rented for 38% more than studios, and 48% more than one-bedrooms, while according to the ACS, they rented for 19% more in both cases.

But accounting for differential vacancies and losses, the story changes considerably: using the Zillow data, three-bedrooms have a true net rental return of 50% higher than studios, and 52% higher than one-bedrooms, while using the ACS data, it is 29% and 22%, respectively. To the extent builders adopt “industry standard” assumptions about stable vacancy rates (i.e., to the extent buildings are priced on contract rent per square foot), builders are leaving money on the table.

Additionally, as we demonstrated in the survey above, a large cohort of American renters value the extra bedroom for an apartment given the same square footage. A simple solution to builders thus directly presents itself: to build apartments with three bedrooms in apartments that they currently only designed for two bedrooms, which is likely to increase the demand—and therefore the rent—of those units.

It may not seem obvious why builders are fixated on rents per square foot: the whole point of building an apartment building is that additional square footage can be added by building additional stories. Square footage should not be the primary constraint on such structures, yet it is, for reasons we elaborate on below.

What Can Be Done?

The real estate industry is not about to reinvent itself overnight, shedding a wide range of structural characteristics that make it hard to build family-friendly apartments. But there are areas where changes could be made. We divide those changes into two categories: private sector practices and government policies.

Private Sector Practices

- Incorporate evidence provided from the survey in this report on pent-up demand and willingness to pay for family-friendly units by adding more such units to large projects: specifically, by increasing the total number of bedrooms in their buildings

- Lenders, builders, buyers, and managers alike should insist that investment return metrics incorporate variable vacancy rates, nonpayment rates, and tenant turnover rates appropriate for units of the given bedroom count, thus implicitly assuming higher occupancy and higher payment rates for buildings with more two- and three-bedroom units. Buildings with lower ratios of bedrooms to units should be seen as having systematically higher operating costs.

- Invest in innovation in technology or construction techniques, which can reduce the construction cost for small- and medium-scale buildings, making it more likely for builders to take risks on family-friendly projects.

Government Policies

- Accelerate the pace at which permits are issued for building projects in general, but especially for projects with under 50 units. Smaller projects have less community impact and should benefit from expedited permitting to enable builders to experiment with new building configurations in a more cost-effective manner.

- Ensure that any parking requirements for buildings are set per unit, not per bedroom. Because land costs for parking (or, alternatively, underground parking) are a significant share of development costs, builders have strong incentives to design apartments in such a way as to minimize parking required. As a result, per-bedroom parking rules directly discourage multi-bedroom units and favor studio apartments.

- Allow single-stair buildings up to four stories. Single-stair layouts are more amenable to multi-bedroom apartment floorplans, and allowing single-stair for smaller buildings will further open new avenues for small multifamily developments and, thus, for more experimentation in form and function.

- Housing trust funds that finance or build apartments at public expense, whether state, federal, or local, should be given explicit, statutory guidance to prioritize housing the largest number of people, and producing the largest possible number of bedrooms, not simply the largest possible number of units.

Conclusion

Apartment-building is booming in America, and that’s not likely to change in the near future. This boom is both cause and a consequence of declining family formation in America. Yet, there are places where market players such as builders and investors could possibly make more money building more family-friendly apartments. Sometimes, the barriers to doing this are institutional or informational—but government policy matters as well. As long as apartments make up such a large share of new housing, it behooves policymakers, developers, and the public at large to take every possible measure to build apartments that are more functional for families.