Highlights

- The “ROAD to Housing Act” does a lot of good work to encourage more housing, but it inadvertently continues the trend towards replacing family-friendly housing with studio apartments. Post This

- With a few adjustments, the “ROAD to Housing Act” can be become a bill that really advances family-friendly housing. Post This

- If barriers are removed to building small apartments but not for family neighborhoods, the result is the bulldozing of family homes for apartments and falling fertility, which is what we’ve seen nationwide. Post This

- The best housing policies include: repealing urban growth barriers, reducing green space requirements, reducing minimum lot sizes, and exempting 3+ bedroom apartments from floor area ratio rules. Post This

America has a housing affordability problem, and it’s hurting family formation. At IFS, we’ve written extensively about this issue, documenting worsening affordability for young families, the demand for starter homes, and options for making multi-family housing more family friendly. Broadly speaking, the agenda we’ve laid out has a lot in common with many “YIMBY” proposals: reduce obstacles to permitting of new housing, reduce minimum lot sizes and parking requirements, raise floor-area ratios, reward jurisdictions that add more housing, etc. Thus, on its face, we should be happy that Congress has stapled a sweeping housing reform act to the National Defense Authorization Act, which just passed the Senate last week. The bill seems to implement many of the priorities we have advocated.

But while the “ROAD to Housing Act” has much to commend it, it would benefit from some improvements. Advanced by Senator Tim Scott (R-South Carolina) but supported by both parties, the Act does a lot of fine work to encourage more housing, but—like other in-vogue housing policies—it inadvertently continues the trend towards replacing family-friendly housing with studio apartments.

In this article, I lay out some problems with the “ROAD to Housing Act,” and how it can be improved. Crucially, these problems can be easily fixed in conference by House and Senate staffers in the next few weeks. With a few adjustments, the “ROAD to Housing Act” can be become a bill that really advances family-friendly housing.

What Housing Is Missing from the Act?

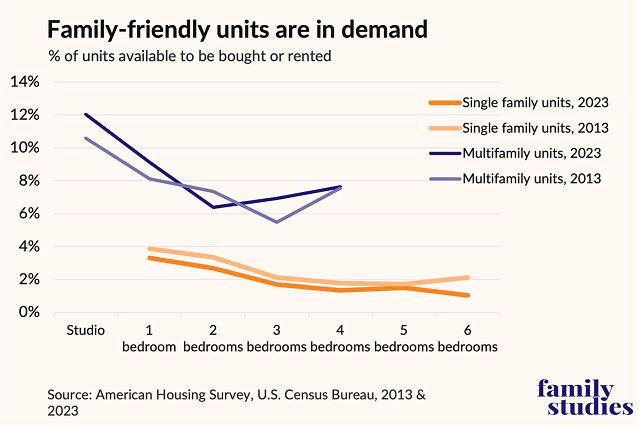

The first thing to ask in any housing conversation is: What kind of housing do people actually need and want? We’ve studied this extensively at IFS. What Americans want, where demand vastly outstrips supply, are modestly-sized single-family houses on modestly-sized lots. That’s where the demand is, and we can prove it. We’ve shown it using survey data on preferences already, but we can show it in actual market data, too. The figure below illustrates the share of housing units by unit bedroom count and type that were currently on the market to be owned or rented in the 2013 and 2023 American Housing Surveys. Vacancies are important because they show what kinds of units are simply not “moving” very fast on the market vs. what kinds of units tend to be hard-to-find.

To begin with, single-family homes are lower vacancy. This is because single-family homes are more desirable for most Americans. That tells us that, for the most part, housing policy should be aimed at removing obstacles to the construction of single-family homes. Moreover, vacancy rates for single-family homes declined between 2013 and 2023: those looking for a single-family home today are facing a tighter market with fewer units available compared to a decade ago.

The story is reversed for multi-family units. First, among these units, studio- and 1-bedroom units have the highest vacancy rates. Small apartments are widely available on the market already: studio apartments are available for move-in tomorrow in every city in America at competitive prices. And indeed, between 2013 and 2023, vacancy rates have risen appreciably for studio- and 1-bedroom apartments. Meanwhile, vacancy rates have fallen for 2-bedroom apartments, risen for 3-bedroom, and been stable for 4-bedroom. But, since 3+ bedroom units are rather uncommon, if we simply lump together all 2+ bedroom units as “all possibly family-friendly apartments,” we find their vacancy rates fell from 7% in 2013 to 6.5% in 2023.

Put bluntly, demand for studio- and 1-bedroom apartments is not robust. The U.S. probably has an oversupply of these units (hence, rising vacancy rates) even as we face a general crisis of affordability in the wider market. That’s because no amount of studio units will ever make a 4-bedroom house affordable for a family. Markets are interlinked and changes in one type of housing do impact others. But markets are not perfectly interlinked, and changes in studio- and 1-bedroom housing supply take a long time to produce very muted effects on market conditions for other types of housing.

The “Road to Housing Act” Ignores Family Housing

Now that we understand that the housing crisis in the United States is specifically a crisis of family housing, we can ask what the “ROAD to Housing Act” does. It has a lot of moving parts; rather than being just one bill, it contains a stack of housing provisions all bundled together. But two exemplary sections of the legislation are worth highlighting as examples of how the law will work.

Innovation Fund

The “ROAD to Housing Act” correctly recognizes that local governments need incentives to adopt policies that yield more housing. As such, it sets up a modestly-sized fund to award grants to localities that add more houses or adopt policies likely to add more houses. That’s a good idea.

But the devil is in the details. When outlining the housing added, the act tells the program manager to ensure housing has been added for a range of incomes (which is fine) but without giving any direction about family status. This matters for a simple reason: if we want to add housing units that are affordable for lower incomes, the easiest way to do that is just to build tons of small studio units. This is often how developers achieve affordability goals. By setting rules based on income levels rather than family appropriateness, the Innovation Fund is implicitly set up to generate more cheap studio units and not increased supply of the units that are in demand.

The statute also outlines policies that could satisfy grantmaking requirements. It lists some good policies, such as: allowing by-right development of duplexes in more areas, reducing parking requirements, adjusting minimum lot sizes and floor area ratios, providing incentives to promote dense development, allowing accessory dwelling units, and more. It’s fine for the federal government to incentivize these policies.

For the most part, housing policy should be aimed at removing obstacles to the construction of single-family homes.

But this is mostly just the wish list of apartment developers. For those of us who want more family-friendly housing, the best policies include: repealing urban growth barriers, reducing green space requirements, reducing minimum lot sizes (which does get mentioned in the bill), and exempting 3+ bedroom apartments from floor area ratio rules. These policies go unnamed.

Raising the height limit for apartment buildings but not chipping away at urban growth barriers (as this bill proposes to do) will yield more studio apartments, but no new family houses. By removing regulatory barriers, the Innovation Fund makes it easier for developers to convert single-family properties into denser multi-unit structures; but in those structures, units tend to be smaller and less family friendly. While this kind of neighborhood change is a natural part of population growth, the fact that the Innovation Fund does not contain incentives to open more land for single-family housing means that family-friendly homes lost to new apartment construction are unlikely to be replaced. As it is written, the Innovation Fund gives money toward bulldozing single-family homes and erecting apartment buildings where comparably few families will live. But with just a few revisions to the text (such as including the items named in the paragraph above in recommended reforms), the Innovation Fund could be a program that truly adds the houses Americans prefer for raising families.

The “Build Now Act”

The “Build Now Act,” like the Innovation Fund, is a great-in-principle provision. It creates a system to slightly reduce federal funding for localities that don’t add new housing and to provide extra funding to localities that do. This is a good idea for many reasons, not least that localities adding more housing have more future service needs, so it makes sense to prioritize funding for them.

But again, the details matter. The Build Now Act specifically rewards localities for adding postal addresses. This makes sense in terms of administrative simplicity, but it has bad side effects. If a rowhome that currently houses a married couple and three children (1 unit for 5 people) gets converted into two apartments for a married couple and a single person each with no children (2 units for 3 people), that would show up as added housing supply, even though population declined and the resulting units are each individually less conducive to future population growth, and even though the units added are unit types where there was already less of a housing shortage (smaller apartments).

Likewise, if a block with eight single-family homes containing 32 residents were bulldozed to add a single apartment building with 60 studio and 1-bedroom units containing 100 residents, the Build Now Act sees that as a huge success: a net increase of 52 homes! And yet, the average people-per-home declined from 4 to ~1.7, and the number of children likely fell from 10-16 to 0-5. This would be fine if new land were opened elsewhere for new family-friendly homes, but since nothing in the “ROAD to Housing Act” encourages this type of approach, such an increase cannot be assumed. Worse, because accessory dwelling units often don’t get their own addresses, localities adding housing this way would get no benefit.

Additionally, for a variety of complex formulaic reasons, the "Build Now Act" mostly subsidizes big-city apartment construction: its calculations make it easier for bigger cities to claim they added lots of housing, give more money to big cities than their housing additions actually justify, and give cities ways to game their allocations through annexations.1 None of this is likely to yield a lot of family-friendly housing, but all of it incentivizes knocking down single-family neighborhoods.

The "Build Now Act" could be fixed easily: a few technical changes to its funding formula would be a good start, and, crucially, localities should have their “housing growth rate” calculated as the lesser of increase in housing or increase in population. Localities adding houses but shedding people should not be rewarded.

The “ROAD to Housing Act’s” family blind spot affects other components as well. For example, the “Build More Housing Near Transit Act” has the same deficiencies in imagining family-friendly housing as the Innovation Fund. That act’s inclusion alongside a few other provisions aimed at urban infill and urban renovations—without including one word about urban growth boundaries—is just another sign this act will add more studio apartments, not family houses. The bill drafters probably do not even entirely intend for this; however, if barriers are removed to building small apartments but not for building family neighborhoods, the result is the bulldozing of family homes for apartments and falling fertility, which is what we’ve seen nationwide.

Lawmakers could push back, in the conferencing process between the House and Senate, with a few small modifications to the “ROAD to Housing Act.” Or, they could leave the draft text as it is now and continue the trend whereby American cities are transformed a bit more every year into forests of skyscrapers where the sounds of children are rarely heard.

Lyman Stone is Senior Fellow and Director of the Pronatalism Initiative at the Institute for Family Studies.

1. The "Build Now Act" also has a very complex multi-step formula for allocating its funds. First, localities are identified as eligible or ineligible to be included in its funding allocation scheme: localities with very low housing costs or high local vacancy rates or recent disasters are excluded from the program. Among the remaining localities, a “housing growth improvement rate” is calculated through the following formula: ( % Change in USPS Addresses Over the Prior 5 Years - % Change in USPS Addresses Over the 6th-10th Years Ago ) / ( Absolute Value of % Change in USPS Addresses Over the Prior 5 Years + Absolute Value of % Change in USPS Addresses Over the 6th-10th Years Ago ). This calculation is odd, because, first, if the housing change 6-10 years ago was zero or near to zero, this calculation will create very extreme and possibly even impossible “divide-by-zero” type results. Moreover, this calculation has the strange effect of treating a locality that goes from 0.002% growth to 0.004% growth as similar to a locality that goes from 2% growth to 4% growth. The apparent reason for this is to avoid disfavoring bigger localities: it’s simply much harder for a bigger locality to boost its growth by 2% than a smaller locality. Or, at least, it may be assumed that this is the case—but the net effect proves to be quite peculiar, namely, that places with very low prior growth in housing have the easiest time qualifying for bonuses. A locality which saw zero or negative growth in the past and which simply adds a handful of houses could actually show up as adding more housing than a locality that aggressively sought to open up to more housing in the present period. Regardless, localities that have above-median housing growth improvement rates then undergo a second calculation assessing how much their funding allocations will be adjusted, and that assessment divides a pot of money between housing-improvement localities by dividing each locality’s total housing stock by the number of bonus-receiving housing units in total. In other words, while adding housing qualifies a locality to get funding, it is already having housing that determines how much they get. But this, again, seems designed to favor bigger cities: bigger cities could qualify for funds with smaller percentage increases in housing, but then receive bonuses based on their total scale, instead of housing added. Both hands of the calculation are designed to shift funding, on net, towards bigger cities that build more apartments. And finally, the rules stipulate that housing unit counts are based on a jurisdiction’s borders at the last date. This means that if a city bans new construction, but a county allows new construction, and then the city recurrently annexes the land where new construction occurs, the city will be rewarded, not the county! This, yet again, seems like a way to provide mechanisms for larger municipalities to capture more benefits. A more intuitive approach would simply be to take the simple difference of USPS address changes in the most recent 5 years vs. the prior 5 years. This approach avoids division-by-zero, avoids extreme values near zero, and is considerably simpler and more intuitive. Furthermore, when funding is to be allocated, it should be allocated based on a locality’s share of gross new address additions, not its share of existing addresses. Finally, localities should have their housing changes calculated using their land area as of the oldest period (i.e. 10 years prior), not the newest, to limit the ability of cities to game their stats through annexations.