Highlights

- If remote work arrangements inadvertently lead young adults to spend more time alone, they may amplify conditions that feed into poorer mental health. Post This

- A fully remote or highly isolated work style can subtly undermine developmental milestones like social scaffolding, romantic relationships, and community ties. Post This

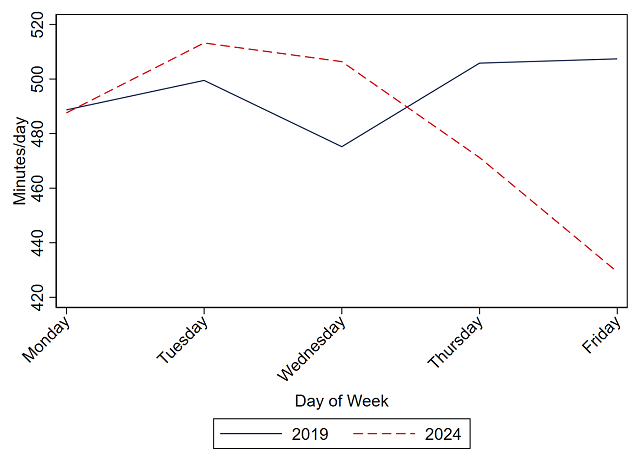

- From 2019 to 2024, average minutes worked on Fridays fell by about 90 minutes remote jobs, whereas on-site jobs saw little change. This “Friday effect” is largest among younger and childless workers. Post This

The rise of remote and hybrid work has reshaped the workweek, especially for younger professionals, according to a recent working paper of mine. Using the American Time Use Survey, I found that Fridays have effectively become the new weekend for remote-capable workers, especially those without children.

From 2019 to 2024, average minutes worked on Fridays fell by about 90 minutes in jobs that can be done from home, whereas on-site jobs saw little change. This pronounced “Friday effect” is largest among younger workers and those without children. One analysis finds that childless employees cut nearly two hours off their Friday work time (from ~542 minutes in 2019 to 427 in 2024), compared to only a half-hour drop for workers with kids. In other words, many 20- and 30-somethings with remote setups are seizing the chance to log off early, especially at week’s end, enjoying a taste of the weekend before it even starts.

Figure 1. Time Allocated to Work Among Remote-Intensive Jobs, By Day

The newfound flexibility goes beyond Fridays. Low-coordination, remote-intensive jobs—roles where tasks do not require constant real-time teamwork— have seen a broad decline in hours worked per day. By 2022–2023, employees in such positions were working 65–92 fewer minutes per day than in 2019, allocating a comparable 65–92 minutes more to leisure instead. This suggests that many young remote workers are using the time saved from commuting or the slack of lighter supervision to relax or attend to personal activities. Prior work of mine has also shown that most of the cutback in work time has flowed straight into leisure (with only a small portion diverted to extra household chores). In effect, the short-term benefit of remote work for these individuals is clear: more free time and autonomy in managing their day.

Less Work, More Leisure — But More Time Alone

What are young adults doing with their newfound “free” time? A closer look reveals a concerning pattern: the extra leisure tends to be solitary. Among remote-heavy workers ages 30-33, the share of leisure time spent with others has declined from 70% to 55%, relative to 2019. In contrast, those in jobs requiring in-person presence saw no significant change—and they still spend the bulk of their leisure hours with friends or family.

Fridays have effectively become the new weekend for remote-capable workers, especially those without children.

Why might this be happening? One reason is asynchronous schedules. A 28-year-old who signs off early Friday afternoon may find that many friends or family are still working or are geographically scattered. The once-common ritual of coworkers grabbing happy-hour drinks or young professionals unwinding together at week’s end has become rarer for those fully remote. In its place might be a Netflix session, solo gym visit, or just additional screen time at home. What at first sounds like work–life balance—trading an hour of work for an hour of “me time”—can morph into social isolation if that leisure time isn’t shared with others.

Isolation and Young Adult Well-Being

Emerging data on the well-being of young adults raise red flags about this isolation. Even before remote work became widespread, researchers noted a decline in the mental and social health of Millennials and Gen Z. The expansive Global Flourishing Study finds that in many countries—including the United States—mental health is a significant “flourishing deficit” for young adults. In the U.S., for instance, the average self-reported mental health score is only about 5.7 (out of 10) among 18–29-year-olds, versus 8.1 for those in their 60s. In 2025, around 83% of young adults said they had experienced feelings of depression in the past two weeks, a rate nearly two-and-a-half times that of senior citizens. Similarly, about 34% of young adults report feeling lonely frequently, far higher than older groups.

Gallup data likewise show that globally 20% of employees feel lonely, with younger and fully remote workers feeling it most. In fact, Gallup’s workplace research calls Gen Z the “loneliest generation”: Gen Z employees are almost three times as likely as Baby Boomers to say they experienced “a lot” of loneliness the previous day. This loneliness has a direct connection to remote work preferences. Notably, Gen Z is the least interested in fully remote roles, with many young workers actively craving more in-person interaction on the job to combat isolation.

All of this suggests that social connection is not a luxury but a lifeline for flourishing in early adulthood. Psychologists have long known that strong relationships are critical for mental health and life satisfaction. The Global Flourishing data further reinforce this: those in romantic partnerships score significantly higher on well-being than those who are single, largely thanks to the support and sense of belonging that close relationships provide. Conversely, when young people feel adrift or alone, their overall life satisfaction and purpose tend to falter. If remote work arrangements inadvertently lead young adults to spend more time alone, they may amplify exactly those conditions—isolation and disconnection—that feed into poorer mental health.

As we embrace the convenience of remote work, we must also count its cost—not just in economic terms, but in human terms. The experiences of younger workers serve as an early warning.

The consequences of prolonged social isolation in one’s 20s and 30s extend beyond immediate mental health. These years are a formative period for building the foundations of adult life—careers, skills, friendships, and families. A fully remote or highly isolated work style can subtly undermine these developmental milestones in several ways:

- Loss of “Social Scaffolding” at Work. In traditional offices, young employees benefit from informal interactions that help them grow. Think of chatting with a senior colleague who offers career advice, or observing how seasoned professionals handle challenges. In a remote setting, much of this osmosis is lost. Unlike older workers who already have established networks and confidence, newcomers depend on guidance and encouragement from managers and mentors. Over time, this could slow their career development and even sap their engagement.

-

Fewer Pathways to Meet Partners. Young adulthood is also when people tend to form long-term romantic relationships. Historically, the workplace has been one common venue to meet a significant other. In the 1980s, nearly 1 in 5 couples in the U.S. met through work. Today, that figure is just around 10%, a decline driven partly by the rise of online dating but likely to be exacerbated by remote work. Fewer days in the office mean fewer casual conversations that spark a friendship or more. Of course, meeting a partner is increasingly moving to dating apps and social media, but those digital avenues do not fully replace the trust and context that can come from getting to know someone in person over time.

-

Weakening Community Ties. Beyond the workplace, a fully remote lifestyle can encourage geographical drifting. On one hand, remote jobs enable young adults to move anywhere—often away from hometowns or high-cost cities— which can be positive for affordability. On the other hand, this freedom can also mean that young workers end up living in new locales where they have no built-in community. They might find themselves working from a small apartment in a city where they do not know anyone, or bouncing to a new location every year. The decline in daily in-person interaction may not immediately register as a problem—until one day, the remote worker looks up and realizes he hasn't felt truly known or supported by a community in a long time.

Counting the Cost of Flexibility

None of this is to suggest that we should revert to the 9-to-5, five-days-in-office grind of old. Remote and hybrid work offer genuine benefits: greater flexibility for family needs, less time wasted on commuting, the ability to hire and work from anywhere, and often higher productivity for focused tasks. For example, many parents, especially mothers, who would otherwise have to drop out of the labor force, are able to continue working, even if part-time. But as we embrace the convenience of remote work, we must also count its cost—not just in economic terms, but in human terms. The experiences of younger workers serve as an early warning. They are reporting record-high loneliness, declining mental health, and fewer close relationships.

How might today’s work-from-home norms reshape the social and emotional development of young adults in the long run? Will the 30-year-old of 2030 be more likely to struggle with anxiety and loneliness because they spent their formative work years isolated in a bedroom office? Could the trends we see now —later marriages, fewer friendships, weaker professional networks—accelerate under a regime of minimal in-person engagement? These are not just individual concerns, but societal ones. Fewer connections and lower flourishing among young adults can have ripple effects on community life, civic engagement, and family stability in the years ahead.

To avoid drifting into a future where flexibility comes at the expense of fulfillment, employers and families alike should take these trade-offs seriously, experimenting with initiatives like:

- Establishing “in-office anchor days,” targeting especially younger staff for mentoring sessions and team-building activities.

- Crafting “team charters” that ensure hybrid work still includes synchronous collaboration and social interaction, thereby mitigating burnout.

- Formalizing mentorship opportunities that pair junior and senior employees around specific projects and measurable goals.

- Coordinating volunteer and civic engagement opportunities outside of the workplace to further build trust and camaraderie.

In the end, the measure of a life, or a career, well lived is not only the output we produce, but the relationships and meaning we cultivate along the way. Flexibility in work is a double-edged sword: it can optimize personal comfort and family life, yet also gradually erode the informal bonds and growth experiences that help young adults flourish. As we navigate this grand experiment in remote work, we would do well to remember that efficiency is not enrichment. Only by counting (and correcting for) the social costs of remote work can we ensure that the next generation thrives—not only at work but also in their personal lives.

Christos A. Makridis is an associate research professor at Arizona State University. He holds doctorates in economics and management science & engineering from Stanford University.

*Photo credit: Shutterstock