Introduction

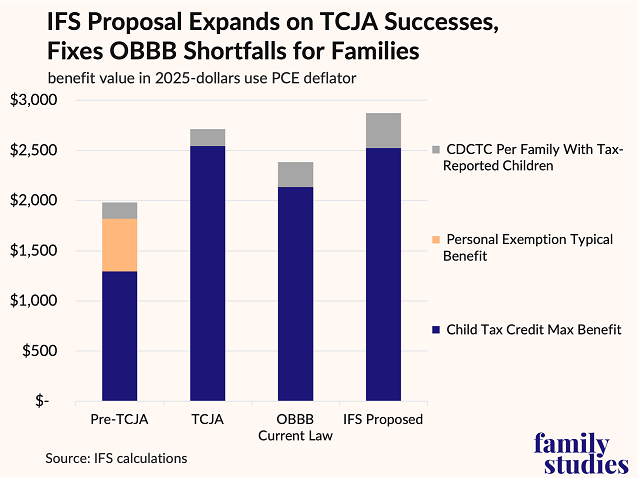

The “One Big, Beautiful Bill” (OBBB), enacted in July 2025, included numerous changes to child-related policies. Most notably, the Child Tax Credit (CTC) maximum benefit was increased from $2000 to $2200, that new value was indexed for inflation going forward, new “Trump Account” investments were established for children born 2025 and later, caps on employer-provided dependent care assistance were raised from $5,000 to $7,500, and the claimable percentage of expenses for the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC) was increased for many filers. Nonetheless, there remain areas where modest changes to the current legislative language could generate large benefits for American families and fix the failure to keep family benefits on par with recent inflation. In this research brief, we outline three changes to family policies in the OBBB that could appreciably strengthen and support American family life. Taken together, these differences would result in the average American working family receiving $500 per child more per year.

First, the CTC’s total maximum value should be increased from the $2,200 level in the OBBB, to $2,600 to preserve its 2017-set value in real terms. Second, to incentivize work, the CTC’s phase-in should begin at the first dollar of income, rather than at $2,500. And finally, the CDCTC should be fixed by removing the marriage penalty for single-earner couples. Its current discriminatory language denies benefits to many working families with child care costs simply because of how couples choose to allocate their responsibilities and paid work. As marriage and birth rates continue to plummet to new lows, Congress should not rest on the limited victories for families achieved in the OBBB, but should instead go further, demonstrating continued commitment to marriage, work, and family life.

Key Findings

- The One Big Beautiful Bill (OBBB) implemented many new supports for families, but benefits for families are below the inflation-adjusted value of benefits in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.

- The Child Tax Credit in particular was not increased enough to protect the inflation-adjusted value of President Trump’s 2017 tax credit for families; it would need to be increased to $2,600 for the TCJA’s pro-family accomplishments to be safeguarded.

- To increase work incentives, the Child Tax Credit could also be adjusted to phase-in with the first dollar of earnings, instead of after $2,500 in earnings.

- The OBBB made some enhancements to the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC), but it did not fix the longstanding discriminatory design of this policy.

- Most of the discriminatory design of the CDCTC can be fixed by allowing benefits to be claimed based on the higher- rather than lower-earning spouse, and by increasing benefits for third children.

Protect the Child Tax Credit

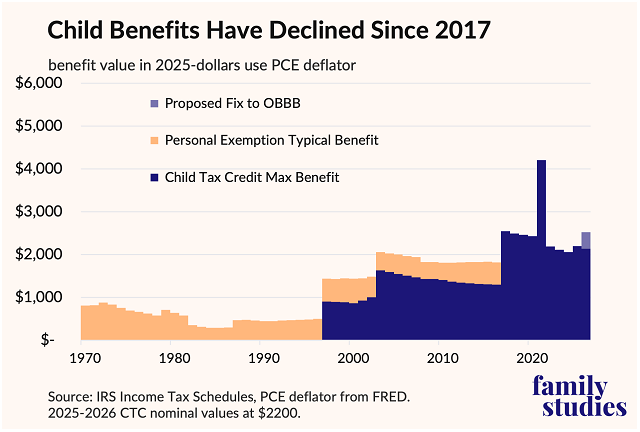

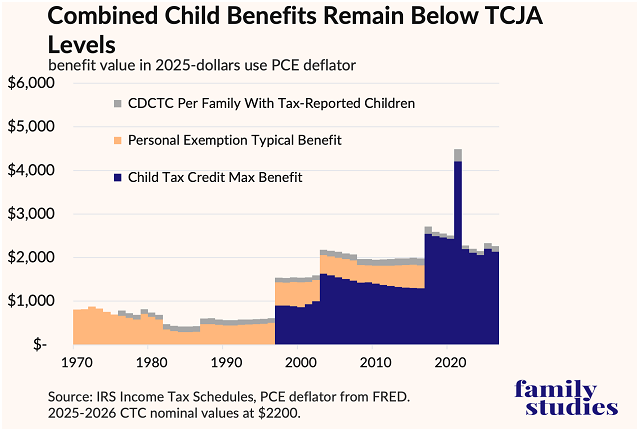

There are two primary mechanisms in the U.S. tax code that have historically benefited families with children directly: dependent personal exemptions (PE), and child tax credits. Personal exemptions—allowing households to exclude some income for each child—date back to the earliest days of the tax code: U.S. law has always recognized the unfairness of ignoring children in the household when calculating tax liabilities, since families with children intrinsically have lower income-per-person, and thus less ability to pay. The 2017 TCJA repealed personal exemptions and instead provided an expanded child tax credit. This benefited most families, but there were complications: the personal exemption had been inflation-adjusted since President Reagan’s reforms in the 1980s, while the CTC was not inflation-adjusted. Likewise, the PE tended to give bigger benefits to higher-income families.

The maximum benefit from the personal exemption was very large, but most families were not at tax brackets high enough to claim such a large benefit. In order to estimate the value of child benefits over time, we convert personal exemption nominal values to estimated tax benefits deriving from those exemptions. To do this, we estimate the value of the personal exemption based on the tax experiences of typical tax filers, rather than the maximum credit (specifically, we take the greater of the Average Effective Income Tax Rate reported by the IRS times the Personal Exemption Value, or the Marginal Tax Rate of Median-Income Household times the Personal Exemption Value). For the CTC, since most claimants claim the full credit value, we simply use the full credit value. We then adjust both estimates for inflation, to track real values over time.

As can be seen, in real terms, tax benefits for families with kids declined from the 1970s through the late 1980s, then rose in the late 1990s and early 2000s. They likely rose again with the TCJA, and especially with the special 1-year expansion of the CTC in 2021 due to COVID, but in general, TCJA benefits have eroded. In 2025 dollars, the original TCJA benefit was worth $2,544.

Thus, to preserve the pro-family shift achieved in the TCJA, we suggest Congress consider expanding the CTC’s maximum credit value to $2,600. Versus the existing OBBB, we estimate that this expansion, occurring via the nonrefundable portion of the CTC, would cost approximately $3-$5 billion in 2026, and approximately $30-$70 billion over 10 years, depending on future inflation, tax rates, and birth rates.

Increase Work Incentives

Families do not get any benefit from the refundable CTC until they have at least $2,500 in income, and at such low incomes, they have no tax liabilities to render them eligible for the nonrefundable CTC. As such, families with zero earnings face smaller work incentives than families with some earnings. For example, if a married couple with two children with $5,000 in earnings had the possibility of increasing earnings by $10,000, under current law, their credit value would increase by $1,500, an effective work-incentive rate of 15 percent. But if the same couple had $0 in earnings and had an opportunity to increase to $10,000 in earnings, their credit value would only increase by $1,125: just an 11% work incentive. Thus, the $2,500 threshold actually reduces the work incentives in the CTC.

We propose a simple fix: the refundable CTC should phase in at the first dollar of eligible income, rather than the 2,501st dollar. This fix would cost, at most, $375 in lost tax revenues per family in the impacted range, though many families would get far less. At the extreme upper maximum estimate, this would cost $4.5 billion in 2026, and likely nearer $2 billion. Likewise, across 10 years, it would cost under $65 billion, likely under $30 billion. In prior research, we have extensively outlined the argument for the first-dollar-phase-in, but it’s worth repeating the arguments in favor of this policy design:

- Increases incentives for zero-earning families to enter the workforce

- Reduces complexity of the CTC

- Specifically provides greater support to working low-income families

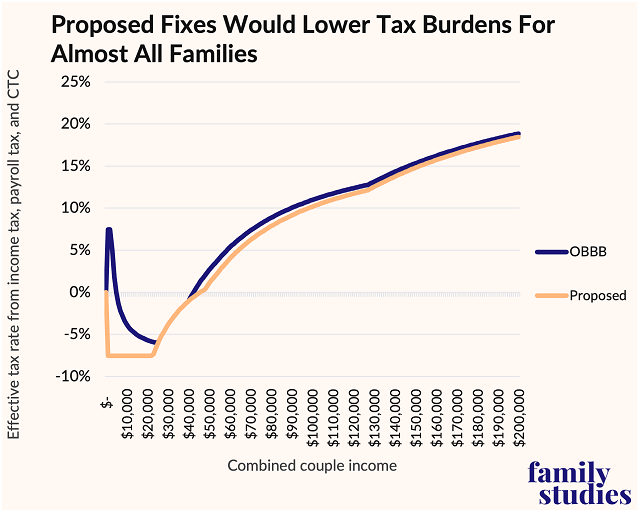

Combining the two CTC-related suggestions, the figure below shows the tax rates faced by a married couple with two children based on standard tax rates and the CTC, but not other tax provisions, under the OBBB as passed vs. our proposed fixes.

As the figure shows, our proposal greatly reduces taxes for working families at modest incomes and provides a modest tax break for middle-income families with children.

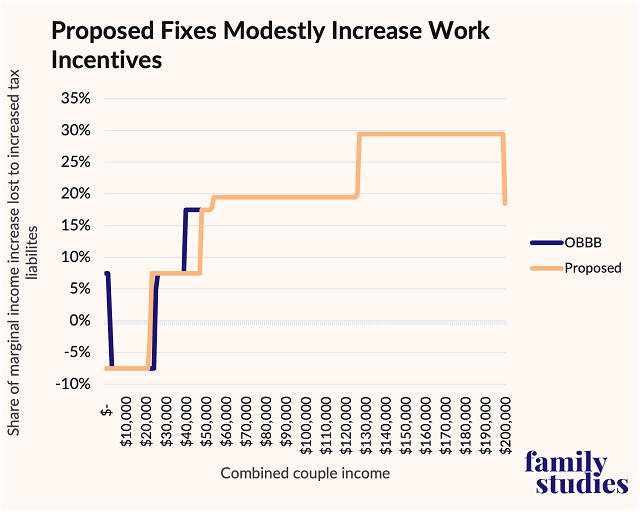

How does our proposal affect work incentives? The figure below shows Implicit Marginal Tax Rates (IMTRs). Implementing first-dollar-phase-in increases work incentives for the lowest-income families, though mostly by pulling work incentives down the income ladder from some other working-class families. But the expansion of the credit size reduces IMTRs, thus increasing work incentives for a nontrivial range of working-class to middle-income families.

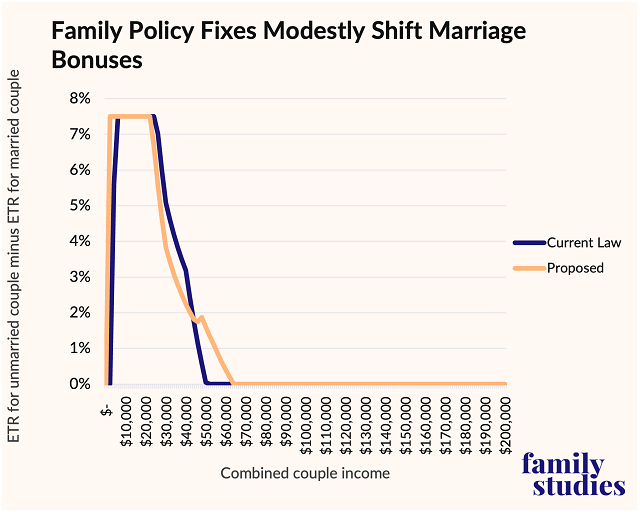

And finally, we assess how these changes influence marriage penalties. We find that these fixes: slightly increase the incentives for very low-earning couples to marry (under $10,000 in combined earnings); reduce the incentives for couples with combined earnings of $22,000 to $44,000 to marry; and increase the incentives for couples with earnings of $44,000 to $64,000 to marry. On the whole, changes to marriage incentives are very small. The small reduction in marriage incentives for a few working-class families is purely due to a shift of those incentives towards lower incomes, incentivizing more marriage further down the income ladder.

Reduce Family Discrimination

The first federal subsidies for child care expenses were implemented in 1954 through a deduction system, which was converted into the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit in 1976, and modified several times since. The OBBB changed the CDCTC to make it considerably more generous, offering much higher adjustment factors for most eligible families. The CDCTC is a famously complex tax credit: families are eligible for it based on a combination of total household income, number of children, income of each parent in the household, educational status of parents, working hours, type of child care purchased, statutorily set adjustment factors that phase-in and phase-out with income, and other factors. This complexity disguises one central key fact of the CDCTC: it is an openly discriminatory tax provision. Its benefits do not scale for larger families but cap at the second child, leaving families with more children no additional benefit. Moreover, the CDCTC completely excludes married-couple families with one income, where the other spouse stays home to care for their child(ren), even if that family has child care expenses that would otherwise be eligible.

This discrimination is based on the prejudicial and incorrect assumption that in families where one spouse stays home, there is no need for child care: yet stay-at-home spouses often have a range of duties drawing them away from their children, and they are prohibited from claiming child care expenses incurred at these times. The federal government has no business deciding for families which child care expenses are legitimate, and which are not. Families are best suited to make their own decisions. In the 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education, 65% of families with children under age 13 either had three or more such children, or had a non-working spouse: thus, 65% of families with children who were age-eligible for the CDCTC faced discrimination against them based on their family status.

Moreover, the NSECE shows that one-earner families do have lots of child care expenses—families with one earner and two parents in the NSECE still average around $2,000/year in expenses on center-based care, camps, preschools, babysitters, and other child care. One-earner couples with three or more children average over $3,000/year in expenses, and 30% of those families average over $6,000/year. It simply is not the case that one-earner families do not have child care expenses.

As such, we propose three fixes to the CDCTC: first, where 26 U.S. Code § 21 section (d) (1) (B) states that the basis for credit calculation shall be the “lesser” of two spousal incomes, we suggest lesser be changed to “greater,” so that any family with a working parent is eligible for the CDCTC. This would maintain the work-incentive function of the CDCTC while removing the statutory discrimination against one-earner families. It may also be necessary to strike “employment-related expenses” from section (a) (1), and to strike the entirety of section (b) (2). In principle, the IRS allows “employment-related” to refer to the higher-earning spouse, so these changes may not be strictly necessary, but removing them would clarify the categorical eligibility of one-earner households.

Secondly, we propose that a section (c) (3) be added, reading, “$9,000 if there are three or more qualifying individuals with respect to the taxpayer for such taxable year.” In essence, this change increases the cap on claimable child care expenses for families with three children under age 13 from $6,000 to $9,000. While it is understandable that taxpayers don’t wish to subsidize enormous child care costs for an open-ended number of children, denying the many three-child families in America a proportional benefit is unfair.

These two changes reduce the share of families with young children facing discrimination from 65% to 5 percent.

Finally, we suggest that section (a) (2) (A) (ii), which excludes spending on overnight camps from CDCTC claims, be stricken entirely. There is no reason to allow parents to claim the CDCTC for a camp that returns kids home at 8 PM, but not for one that returns them home at 8 AM the next day.

These three fixes would transform the CDCTC in important ways.

- First, they would simplify the credit: one line of the credit form (identifying the lower-earning spouse) could be removed, allowing taxpayers to simply specify the higher-earning spouse; moreover, families would no longer have financial incentives to deny their kids participation in campout nights at summer camp, an absurdity of the current law. If provisions related to employment-relatedness are also stricken, this would dramatically simplify child care eligibility determinations by the IRS, reducing filing burdens for families and reducing auditing costs for the IRS.

- Second, this change would eliminate discrimination based on family work divisions and reduce discrimination based on family size.

- Third, this proposal would help fix the longstanding decline in the value of the CDCTC by making more families eligible and raising the cap on eligibility.

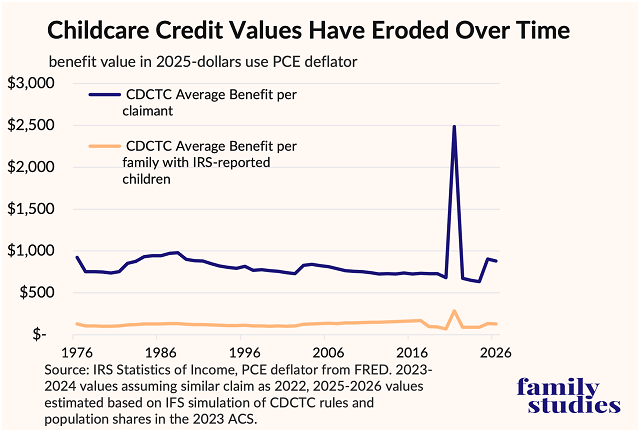

To begin with, its’s worth reviewing the history of the CDCTC. In terms of real value, the CDCTC peaked in the mid-1980s, and has since declined, except for a huge COVID-era increase in 2021—at least among families who claimed the CDCTC. But very few families actually claim the CDCTC. Many are ineligible for income reasons: they lack enough tax liability to claim the CDCTC, which is nonrefundable, an issue these families face with the nonrefundable CTC as well. Others are ineligible for categorical reasons: they have just one earner, or used the wrong kind of child care, or did not pay for child care at all, or some other of many reasons the CDCTC excludes individuals. Still others may have been eligible but simply forgot to, failed to, or could not figure out how to claim their credits.

As a result, if we look at the value of the CDCTC per family that claimed a child tax credit (i.e., a benchmark for children in the tax population), the CDCTC is far smaller. Real benefit value on this basis increased from 1998 to 2016 as more families claimed the CDCTC due to rising child care costs, even as the CTC-claiming population was fairly stable. With the CTC expansion in 2017, more families claimed the CTC. In sum, the average tax family with reported children can expect less than $200 off their tax bill from the CDCTC. Adding the CDCTC to our earlier graph on CTC and PE, we can see how small the CDCTC is as a benefit for families:

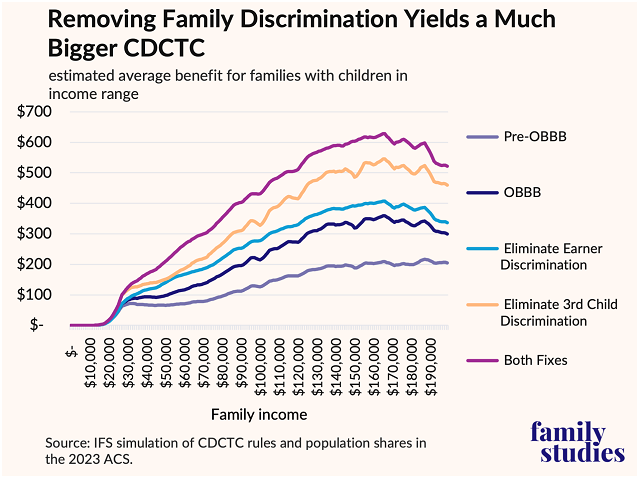

What effect would our proposed change to the CDCTC have? To estimate this, we use the 2023 American Community Survey to simulate the effect of different CDCTC eligibility rules.

The results are striking. First, the OBBB considerably expands the CDCTC. While public commentary has described OBBB changes to the CDCTC as relatively minor, they do not appear minor: total spending on the CDCTC is likely to rise considerably.

Second, removing the discrimination against one-earner families increases benefits further. Whereas OBBB changes disproportionately benefited higher-earning families, eliminating one-earner discrimination provides roughly stable benefits to families from $40,000 to $200,000 in income, and thus much larger relative benefits for lower- and middle-income families.

Third, allowing a third-child benefit disproportionately benefits a few families with incomes around $20-$40,000 who had unusual tax liability patterns, as well as higher-earning families. But remember, a higher-earning family with more children is not as rich as it might seem. Healthcare subsidies under the Affordable Care Act extend to 400% of the poverty line, representing an understanding that families in this range are basically middle-income. A family at 400% of the poverty line with one child has $107,000 in income; with two, $129,000 in income; with three, $151,000 in income. The large benefit increases shown above are not flowing to families who have the highest purchasing power per family member; it just so happens that it takes a lot of money to support a family of five in America today.

How much would such a change cost? Fixing one-earner discrimination as we propose costs about $2-$4 billion in 2026, and plausibly $25-$50 billion over the next decade. Fixing third-child discrimination costs about $3.5-$5 billion in 2026, and plausibly $35-$60 billion over the next decade. Thus, our proposed reforms here cost a combined $60-$110 billion over the next decade.

America Can Afford to Fix Family Policy

Over the next decade, these combined proposed fixes would cost between $115 and $245 billion for taxpayers. That is a considerable sum. But it is worth paying—and the revenue can be raised without raising income taxes. Preserving the pro-family legacy of the TCJA, eliminating unfairness in child care programs, and rationalizing family policy is worth a modest price; and the price is, indeed, very modest.

The fixes we have proposed pencil out to around $11-$25 billion in additional budgetary costs per year. This is a not a small sum in principle, but it is a drop in the bucket compared to federal revenues, and we have sensible suggestions on how the money could be raised without raising income taxes or cutting other family programs.

As we argued in previous research on the CTC, policymakers could consider special per-usage-minute excise taxes on pornography providers or producers, social media companies, and higher tax rates on gambling—similar to excise taxes already charged on gun manufacturers, gasoline, airline tickets, fishing equipment, indoor tanning services, ship passengers, expensive insurance policies, and alcohol, for example. In 2023 the Federal government raised $209 million from excise taxes on fishing gear and bows-and-arrows, and $68 million from taxes on tanning salons; these are small amounts overall, but they point to the absurdity of leaving addictive pornography and social media untaxed. Likewise, excise taxes on gambling (especially addictive online gambling) already exist: a paltry 0.25% of wages are charged as an excise tax, which raised $375 million in federal revenues in 2024 vs. industry revenues of almost $72 billion.

Across all excise taxes, the Federal government raised almost $100 billion in revenue in 2023 alone; new excise taxes for addictive digital products or higher rates for existing products like alcohol would be a reasonable way to cover the entire revenue needs envisioned in this brief. Excise tax revenues would need to rise by only 10-25%, a perfectly feasible sum, especially if policymakers considered levying taxes on heavy electric vehicles to replace losses on gasoline taxes.

There are plenty of revenue options available for policymakers to pay for these fixes. For comparison, the OBBB raised annual spending on agricultural insurance subsidies by $6.3 billion per year, added $1 billion per year to Mars mission spending, $1.2 billion per year to Air Traffic Control improvements, $2 billion per year to Coast Guard readiness, $100 million a year to expanded inland waterways development, $200 million a year to expand the Adoption Credit, $200 million a year reducing taxes on distilled liquors, $4 billion a year on expanded detention facilities for illegal immigrants, and $800 million more a year on nuclear waste management. We highlight these not to suggest they are good or bad expenditures—but simply to note that the scale of spending change we suggest is, well within the range of budget items that never made the news at any stage of budget debates: these are small spending items.

Yet, the benefits to families are large. The difference between the OBBB and our proposal is, for a typical family, almost $500 per child. Most of those benefits flow to working-class and middle-income families, since the first-dollar phase in, one-earner discrimination fix, and third-child discrimination fix all disproportionately benefit these families. At a time when falling birth and marriage rates show that American families are clearly struggling, it is advantageous for Congress to at least ensure families get as good a deal as President Trump delivered for them in the TCJA. The OBBB did not fully deliver that. But with a few enhancements, Congress can.