Highlights

- Our working paper shows that unexpected inflation had a negative, significant impact on the total fertility rate in the U.S. from 2004-2023. Post This

- Women in their early 20s are the most responsive to unexpected inflation shocks. Post This

- Recent trends in the U.S. show a striking divergence: inflation surged sharply after 2020, while fertility rates dropped further below replacement. Post This

Over the past several years, American households have experienced one of the sharpest increases in the cost of living in decades. Rising prices for housing, child care, healthcare, and education have coincided with heightened economic uncertainty following the COVID-19 pandemic. At the same time, U.S. fertility rates have continued their long-run decline, prompting renewed debate about whether economic pressures are reshaping family formation decisions. While discussions often focus on cultural change or shifting preferences, the affordability of raising children in an era of elevated and unpredictable prices may be an underappreciated part of the story.

Here, we highlight our new working paper that sheds light on how unexpected inflation—price increases that exceed what households anticipate—affects fertility decisions in the United States. By emphasizing the role of economic uncertainty rather than inflation alone, these findings help connect today’s cost-of-living concerns to broader demographic trends.

The Link Between Inflation, Expectations, and Fertility

Does inflation reduce fertility? Fertility decisions tend to be forward-looking, shaped not only by current economic conditions but also by households’ expectations about future income, prices, and economic stability. Previous research even refers to fertility as a “leading economic indicator,” since conceptions tend to decline several quarters before actual economic decline registers in the data. This might be more surprising to researchers than anyone who is currently in the midst of growing their family—of course one takes future economic conditions seriously when discussing future children with their spouse.

One way that future economic plans are affected by forces outside of a couple’s control is when inflation—and thus the cost of raising a child—rises unexpectedly. Research suggests that households revise their expectations upward if rising inflation rates are covered in the news, but this still leaves budgets tighter than before (until wages adjust, which is usually not immediately). And as economics professors repeat often in class: “less is demanded at a higher price.” If the cost of raising a child increases, couples will have fewer children.

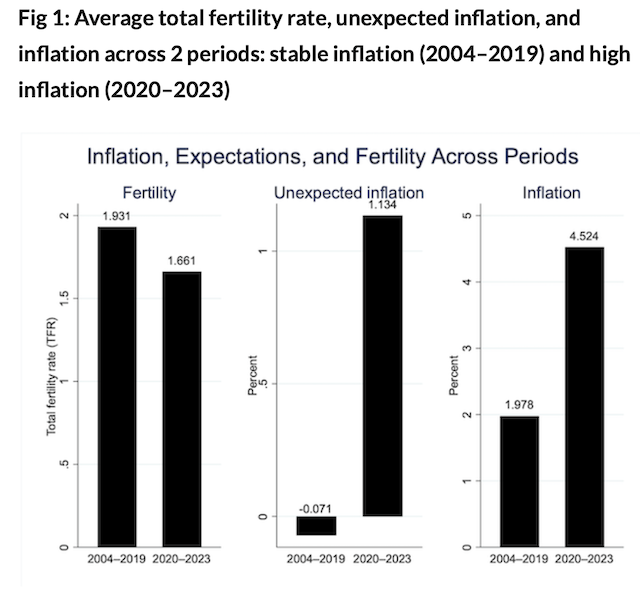

As Figure 1 illustrates, recent trends in the United States show a striking divergence: inflation surged sharply after 2020, while fertility rates dropped further below replacement. During the stable inflation period (2004-2019), inflation averaged just 1.98%, and unexpected inflation was slightly negative (-0.07%), suggesting households' expectations closely align with actual inflation. The total fertility rate was relatively higher during this period (1.94 children per woman). By contrast, the post-pandemic period (2020-2023) saw inflation averaging 4.52%, with unexpected inflation turning positive (1.13%). Average fertility was down 15% to 1.66 children per woman in this period.

From a monetary policy perspective, when inflation is high and above expectations, the central bank may raise nominal interest rates. This increases borrowing costs, reduces housing affordability, and could prompt households to postpone childbearing decisions. On the other hand, a monetary policy that anchors inflation expectations and promotes price stability benefits households and may encourage couples to have more children. There is an underappreciated link between sound money and sound family life.

The main empirical result of our working paper shows that unexpected inflation had a negative and significant impact on the total fertility rate in the United States from 2004-2023. Specifically, a five percentage-point increase in unexpected inflation results in 15-25 fewer births per 1000 reproductive-aged women. These results align with economic theory: when inflation rises above expectations, households experience a decline in real purchasing power. Consequently, greater economic uncertainty and lower real income discourage childbearing. Families may respond by postponing births or by reducing desired fertility.

Young Women Respond Most to Inflation Spikes

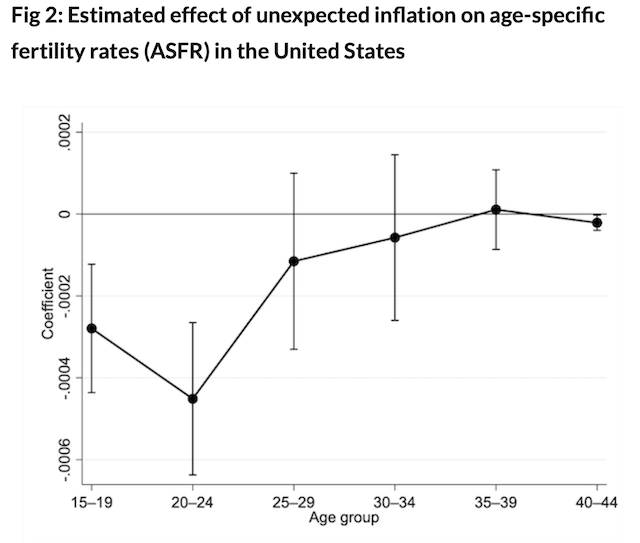

Our paper further examines the effect of unexpected inflation on age-specific fertility rates (ASFRs). Younger women often have more scope and flexibility to postpone childbearing, especially when economic conditions appear unfavorable. Older women, by contrast, have less flexibility, so their fertility responses tend to be smaller and reflect changes in completed family size rather than timing.

The results of the regression analysis, shown in Figure 2, suggest that women in their early 20s are the most responsive to unexpected inflation shocks. While much of this decline might be due to postponement, it is not necessarily true that all of these postponed-but-desired births will lead to actual births. Continued economic uncertainty could lead to further delay, and waiting to have children often translates into having fewer children than desired.

Stable Economic Policy Supports Higher Fertility

At a time when both inflation and demographic trends are central to policy debates, these findings demonstrate an important link between the two. Credible, stable monetary policy influences more than price stability; it also provides an important foundation for family formation and household fertility plans. Monetary policy that anchors inflation expectations and commits to price stability can support couples in their fertility goals. Policies that reduce economic volatility and keep family benefits linked to inflation rates may therefore play an important role in shaping the demographic trajectory of the United States in the years ahead.

Ahmed A. Adesete is a graduate student in Economics at the University of Mississippi. Clara E. Piano is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Mississippi.

*Photo credit: Shutterstock