Highlights

- The home sets the trajectory for developing cognitive skills, character traits, and the soft skills associated with long-term flourishing. Post This

- The states with the two worst scores on the Index (Louisiana and Mississippi) have the highest rates of childhood poverty. The two highest-scoring states (Vermont and North Dakota) have lower rates of childhood poverty. Post This

- Healthy family structures shape a child’s potential for mobility. Likewise, the surrounding public policy environment can either support or impede those opportunities. Post This

Family life sets the foundation for social mobility. Before a child ever encounters the labor market, formal schooling, or the broader institutional environment, the home sets the trajectory for developing cognitive skills, character traits, and the soft skills associated with long-term flourishing. From Raj Chetty’s neighborhood studies that uncovered the importance of growing up around present fathers to Melissa Kearney’s recent book on the irreplaceability of the two-parent family structure, research consistently shows that stable and engaged family environments predict better outcomes for children across a wide range of indicators.

Our new report for the Archbridge Institute, the 2025 Social Mobility in the 50 States Index, incorporates parental engagement and family stability as factors that shape one’s ability to achieve his or her goals. The parental engagement and family stability variables included in the 2025 Social Mobility Index illuminate the natural barriers children may face and how supportive environments can mitigate them. While education, entrepreneurship, and the rule of law remain critical pillars of a state’s mobility metrics, family factors constitute the first stage where opportunity can either take root or begin to wither.

Parental Engagement, Family Stability, and Child Poverty

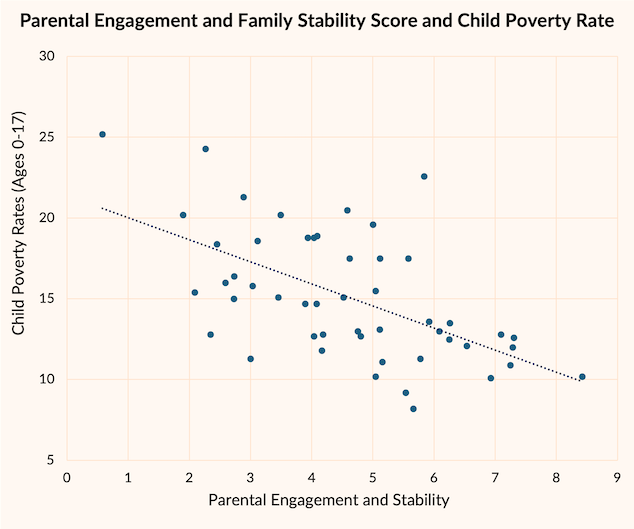

Figure 1 below illustrates the relationship between a state’s “Parental Engagement and Family Stability” score from the Social Mobility Index and its rate of child poverty. Parental Engagement and Family Stability is an index scored from 0 to 10, with higher scores corresponding to more parental engagement and higher rates of family stability. Although this report does not attempt to establish a clear, causal connection between child poverty and family engagement and stability, there are some interesting associations.

The states with the two worst scores in “Parental Engagement and Family Stability” (Louisiana and Mississippi) have the two highest rates of childhood poverty (25.2% and 24.3%, respectively). On the other hand, the two highest scoring states (Vermont and North Dakota), have notably lower rates of childhood poverty: just 10.1% and 10.2%, respectively; these are the 3rd and 4th lowest rates in the country in 2023.

While higher rates of parental engagement and family stability are strongly associated with smaller shares of children living in poverty, this graph does not indicate the direction of causality. It is likely true that poverty both causes low parental engagement and family stability while also resulting from it. However, from a child’s perspective, the choices of parents come first and shape his or her opportunities.

Measuring Parental Engagement and Family Stability

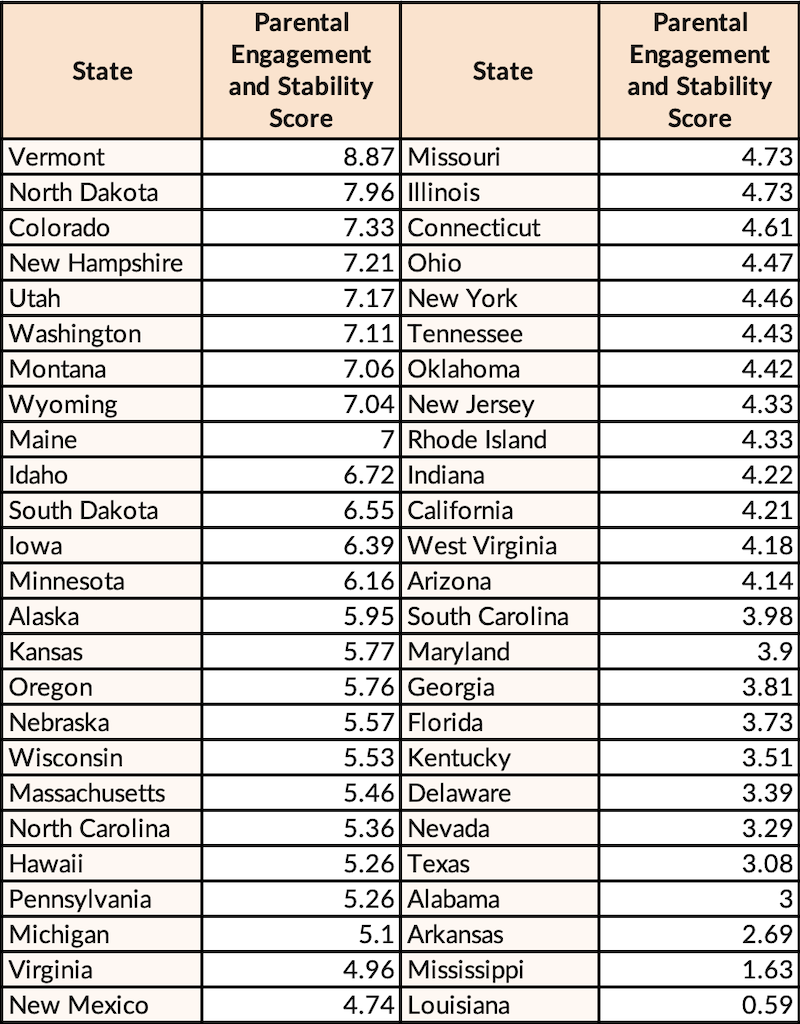

We use three indicators from the 2023 National Survey of Children’s Health to capture everyday investments parents make in their children’s development: reading to young children, attendance at a child’s activities, and the frequency of shared family meals. Because higher engagement supports mobility, a higher value in each of these variables contributes to a higher social mobility score for a state, as shown in the table below.

Engagement is generally high in the states but a closer look reveals some variation and regional trends. On average, about two-thirds of parents report reading to children ages 0–5 most days of the week. States in New England and the Upper Midwest perform best, with Vermont posting the highest rate (86.8%). Southern states tend to lag, with Louisiana recording the lowest rate (51.2%). Nearly 84% of parents report regularly attending school, sports, or community activities. North Dakota leads (91.2%), while California ranks lowest (79.3%). Three-quarters of families report eating together most days of the week. Wyoming leads on this dimension (81.8%), while New Jersey records the lowest rate (68.1%).

Table: Parental Engagement and Family Stability Scores (Highest to Lowest)

Two data points from the 2023 American Community Survey make up the family stability subcategory: the share of births to unmarried women and the share of households headed by single parents. Unlike parental engagement, higher values on these measures indicate greater instability and are therefore associated with lower mobility scores.

The share of births to unmarried women varies substantially across states. The national average is just over 30%, but Utah stands out with the lowest rate (15.7%), demonstrating unusually strong marriage and family formation norms. Louisiana sits at the opposite end of the distribution, with nearly half of births occurring outside marriage (45.5%). The share of households headed by single parents follows similar geographic patterns. Mississippi has the highest rate (8.7%), while Vermont has the lowest (3.7%).

Natural and Artificial Barriers to Social Mobility

Family dynamics are at the intersection of what the Social Mobility Index identifies as natural and artificial barriers. Most elements of the “Parent Engagement and Family Stability” subcategory—such as reading habits, shared meals, and household structure—reflect natural barriers rooted in the home environment. While these factors are primarily internal to families, they remain sensitive to broader economic and institutional settings that shape the time, resources, and stability parents can provide.

For example, an artificial barrier to social mobility (one that is imposed by external forces and can be addressed with public policy) is childcare regulation. When childcare markets are mis-regulated, which can increase costs and decrease options without adding any clear benefits, families may face sharper work-family tradeoffs and tighter budgets than would otherwise be the case. An open and flexible childcare market can complement strong family environments by giving parents more bandwidth to read with their children, participate in activities, and maintain household routines such as shared meals. A recent working paper even finds that states with fewer childcare regulations tend to have higher fertility rates, indicating that more women are achieving their fertility goals (since average ideals exceed actual births in every state).

The share of births to unmarried women varies substantially across states. The national average is just over 30%, but Utah stands out with the lowest rate (15.7%), demonstrating unusually strong marriage and family formation norms. Louisiana sits at the opposite end of the distribution, with nearly half of births occurring outside marriage (45.5%). The share of households headed by single parents follows similar geographic patterns. Mississippi has the highest rate (8.7%), while Vermont has the lowest (3.7%).

The home sets the trajectory for developing cognitive skills, character traits, and the soft skills associated with long-term flourishing.

Another major artificial barrier to social mobility is the presence of marriage penalties arising from the mistreatment of joint income by the tax code and means-tested welfare programs, which directly punishes parents for attempting to provide stability to their offspring. When a lower-earning spouse joins his or her income to a spouse with higher earnings (potentially a higher tax rate), a financial penalty may be levied. Even worse, however, are the marriage penalties present in nearly all the cash, food, or housing means-tested welfare programs, which remove benefits if a single parent were to marry and raise their household income. Recent research argues that removing such penalties would result in 13.7% more low-income, single mothers getting married annually.

Natural and artificial barriers to social mobility work in tandem. Healthy family structures shape a child’s potential for mobility, and at the same time, the surrounding public policy environment can either support or impede opportunities for parents to promote a bright future for their children. While mitigating natural barriers remains the responsibility of parents, the removal of artificial barriers to family stability are the responsibility of each citizen.

Justin Callais is the Chief Economist of the Archbridge Institute. Anna Claire Flowers is an Economics PhD student at George Mason University. Clara E. Piano is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Mississippi.

*Photo credit: Shutterstock