Executive Summary

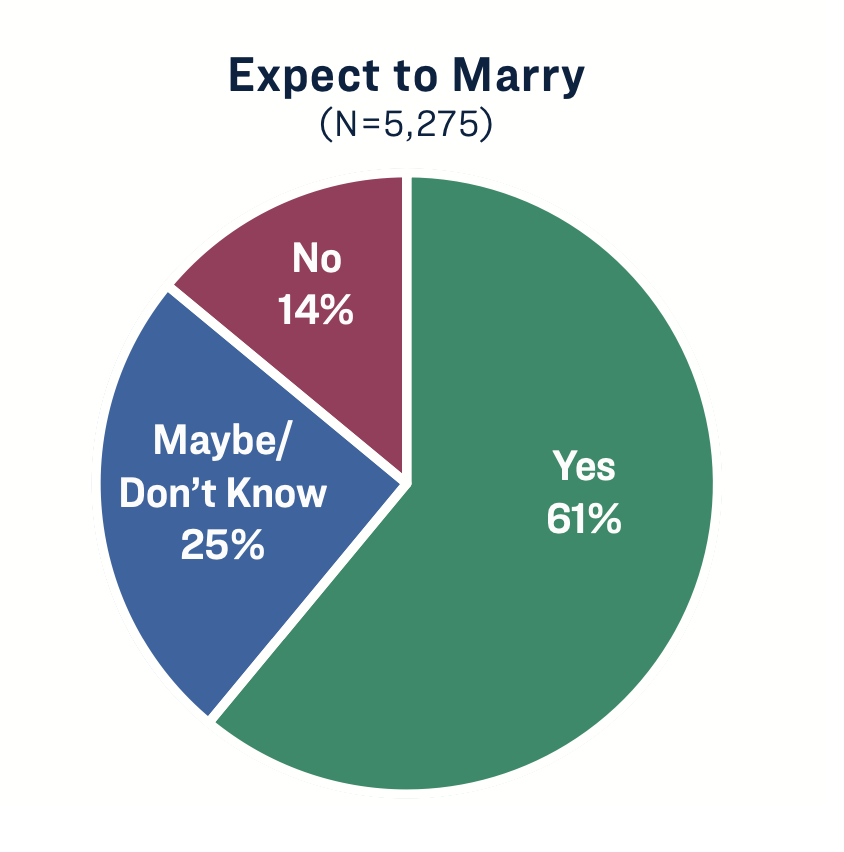

Young adults today are living in a depressed dating economy. In this 2026 State of Our Unions report, we pursued greater insight on the challenges of contemporary dating through the 2025 National Dating Landscape Survey, a nationally representative sample of 5,275 unmarried young adults ages 22–35 in the United States. We focused mostly on the dating experiences of those single young adults who expect to marry (86%; N = 4,539).

What did we learn?

Overall, we found evidence that many young adults are experiencing a dating recession during their prime dating years. Most young adults are not dating much and many are struggling with significant barriers to initiating dating relationships and pursuing their desire to one day marry and have a family. Most young adults across our country endorse relatively traditional purposes for dating and do not express an overt fear of commitment, but many lack the needed skills for dating and the resilience to handle the natural ups and downs of relationship starts and stops along the journey of dating. Here are some of the key trends we found:

- Only About 1 in 3 of Young Adults is Actively Dating

Only about 30% of young adults reported that they are dating, either casually or exclusively. When asked how often they were dating, only 31% of young adults – a quarter of women (26%) and a little more than a third of men (36%) – reported that they were active daters (dating once a month or more). Nearly three-quarters of women (74%) and nearly two-thirds of men (64%) in our survey reported they had not dated or dated only a few times in the last year. These numbers are noteworthy given that about half (51%) of the young adults in our national survey expressed interest in starting a relationship.

- Young Adults Lack Confidence in Their Dating Skills

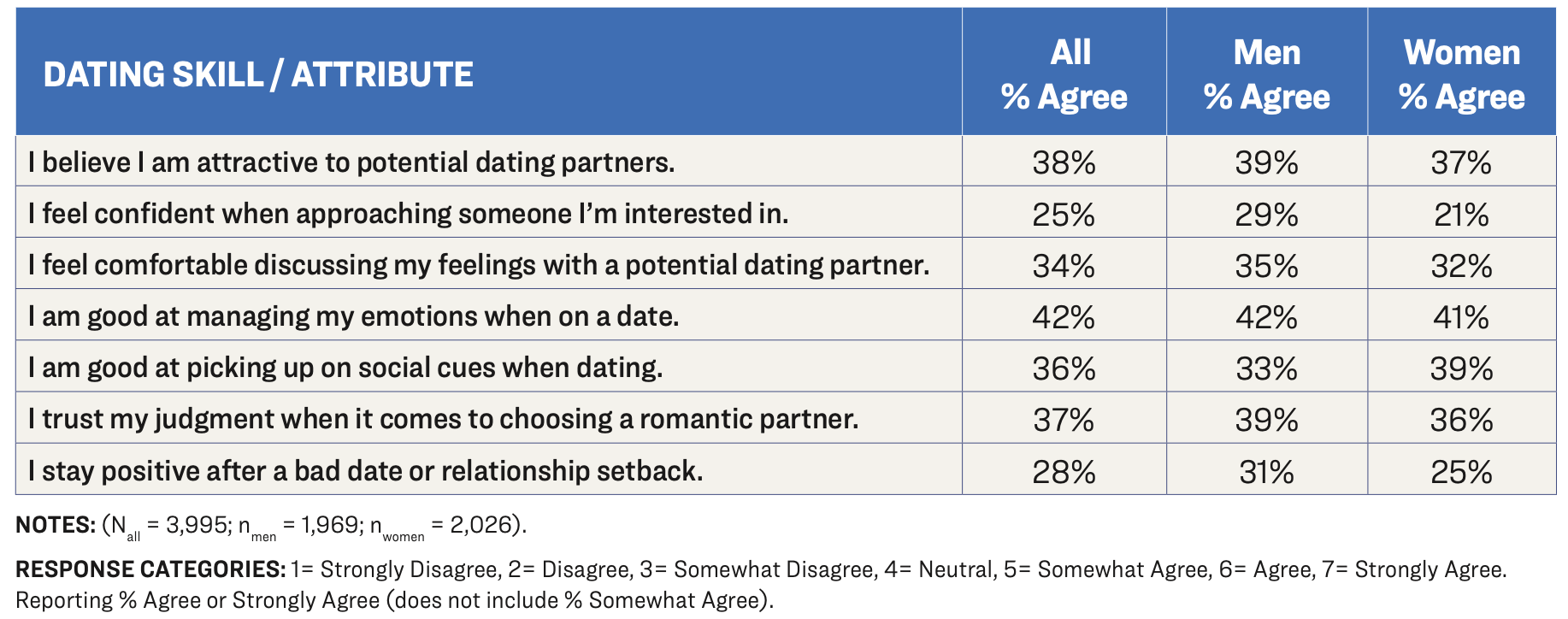

We also found that many young adults lack faith in their dating skills and their ability to initiate a promising romantic relationship. In fact, it is safe to say that among the rising generation dating confidence is low, with only about 1-in-3 young adults expressing much faith in their dating skills. Only about 1-in-3 young adult men and 1-in-5 young adult women expressed confidence in the fundamental skill of being able to approach someone they were romantically interested in. Less than 4-in-10 (37%) said they trusted their judgment when it comes to choosing a dating partner. A similar minority of young adults expressed confidence in their ability to discuss feelings with a dating partner (34%) and picking up on social cues on dates (36%).

-

Young Adults Desire a Dating Culture Aimed at Forming Serious Relationships

Despite a common narrative that young adults are only interested in casual dating and unattached hooks-ups, we found that young adults – both women and men, younger and older – strongly endorse a dating culture focused on forming serious relationships (83% of women and 74% of men) and creating emotional connections (83% of women and 76% of men). These more traditional purposes for dating are aimed at building committed romantic relationships and learning how to facilitate personal growth in those relationships. While dating frequency may be low, most young adults seem to yearn for the connection of serious dating and marriage relationships.

- Money Worries, Self-confidence, and Past Dating Experiences are Big Barriers in the Modern Dating Landscape

Young adults reported significant financial and social/emotional barriers to dating. The biggest barrier to dating they expressed was not having enough money, endorsed by more than half (52%) of respondents (58% of men and 46% of women). Contemporary dating is often focused on commercial activities, and young adults often feel they can’t afford to date in this way. Respondents also frequently reported that personal factors get in their way with dating. At the top of this list were lack of confidence (49%) and bad dating experiences in the past (48%).

- Dating Resilience is Low Among Young Adults

Dating resilience is low among young adults, with only about a quarter (28%) reporting that they can stay positive after a bad date or relationship setback. More than half (55%) agreed that their breakups have made them more reluctant to begin new romantic relationships. This study shows that there is a marital-expectations vs. dating-skills gap for most young adults today.

This gap calls for a concerted effort to teach young adults healthy dating skills, something that receives little attention from the general culture or even the relationship education field. Young adults could use some basic help in building dating skills. Their desires and attitudes are not the problem. They want to build real human connections, form serious relationships, explore what they want in a future long-term partner, and desire the personal growth that comes from forming serious romantic relationships. And contrary to common beliefs, most are not afraid of commitment or losing personal freedom, and few fear that dating will interfere with their educational and career plans. Our young adults need effective road maps that guide them to and through the dating experiences that will connect their marital expectations to actual unions.

The Dating Recession: How Bad Is It and What Can We Do?

There is good news about marriage that all can cheer: Marriages are significantly more stable today than they were four to five decades ago. Granted, much of this stability bonus is a result of who is marrying. Couples with riskier profiles for marital breakup have become a decreasing proportion of all marrying couples. Couples who marry today are more likely to have a set of characteristics that lend themselves to more stable marriages. For instance, they are better educated, more financially stable, more religious, and less likely to marry as teens. Still, regardless of its causes, greater marital stability is something to celebrate because of the known benefits that stable, healthy marriages give to children, adults, and their communities.

Hidden in this encouraging trend, however, is a paradox: Increasing marital stability exists alongside a strong trend of fewer adults getting married. First-marriage rates have fallen by more than 10% over the past two decades, continuing a steady descent since the 1970s. Demographers now estimate that a third of young adults born in the early decades of the twenty-first century will never marry. (Remarriage rates are tanking, too.)

If our only goal is to promote marital stability, then a falling marriage rate, with couples who possess riskier divorce profiles opting out, is not a concern. But if marriage itself is a crucial social and personal good, then a substantial decrease in the number of adults who marry across the life course is a discouraging counterweight to the good news of increasing marital stability. It is hard to celebrate stronger marriages when fewer and fewer young people are entering them. Socially, this is ambivalent news.

Numerous scholars have explored why fewer young adults are marrying. Increased focus on post-secondary education and careers during young adulthood and a declining cultural emphasis on needing to be married – a phenomenon dubbed “the Midas Mindset” – are commonly cited factors. But one straightforward reason for the decline in marriage rates that has not received much attention is the dating system. Many young adults today complain that the dating system is badly broken. They grumble about dating apps that present an abundance of options a mere swipe away and that promote an attitude of relational consumerism. And the repetitive cycle of matching, messaging, and meeting that ends in disappointment leads to significant dating fatigue and cynicism about the whole process. Similarly, they dislike the hook-up culture that pervades dating and its emphasis on casual sex over building soulful relationships.

If the onramps to our marital highways are bumpy, broken, or blocked, it is no mystery why many young adults struggle to reach their expected marital destinations. Or to use another analogy, the contemporary dating economy is struggling, perhaps in a recession. Despite a broken dating system, a healthy majority of young people today still expect a future that includes marriage. (Although this is less and less so for contemporary young women who lean left ideologically.) Can the contemporary dating system – such as it is – get them there? What is the state of the modern dating economy as we begin the second quarter of America’s twenty-first century?

This report details findings from a new national survey of American young adults’ attitudes, beliefs, and experiences about dating in contemporary America, with a special focus on those young adults who have expectations for marriage – some strong, some modest, and some just uncertain but open to possibilities. What are their attitudes and beliefs about dating and marriage? What are their current dating behaviors and experiences? Importantly, what are the barriers and challenges they face in this dating economy? And, importantly, if we are in a dating recession, what can we do to revive this economy?

To preview our findings, the story that emerges out of this national survey is one of a dating recession for young adults in their prime dating years; they simply are not dating much, struggle with significant barriers, and lack confidence in their dating skills. They endorse relatively traditional purposes for dating (and do not fear commitment) but they lack the needed skills for dating and the resilience to handle its inevitable emotional wounds. As a result, they experience a loss of romantic connections – connections that prime their souls for the richest experiences humans can have.

We hope this State of Our Unions report can kindle cultural and professional conversation about this new challenge to marital formation and spur efforts on the part of parents, relationship educators, counselors, and even policy makers to help young adults improve their dating skills and opportunities.

2025 National Dating Landscape Survey

We pursued greater insight on contemporary dating in the 2025 National Dating Landscape Survey, a nationally representative sample of 5,275 unmarried young adults ages 22–35 in the United States. We see these as the prime dating years for first marriages. The dating experiences of younger 18–21-year-olds are even more disconnected from marriage, which is more than a decade away for most of them. So they are not our focus here. Similarly, dating for those over age 35 may be qualitatively distinct from that of younger adults. We limit our focus to those in the prime dating period for first marriages.

In addition, our focus in this report is on those unmarried young adults who say they expect to marry someday. Fourteen percent of our sample (N = 736) said that they do not expect to marry. Their stories are worth understanding too, but their dating experiences are disconnected from expectations for a future marriage. So instead, we focus on the 86% of respondents (N = 4,539) whose dating experiences are potentially connected to a future marriage, including those who definitely have expectations to marry (61%, n = 3,233) and those who maybe have expectations or just don’t know (25%, n = 1,306).

Findings: Marital Expectations and Salience

Ideal Age to Marry

Before diving into young adults’ specific dating experiences, we were curious if young adults who were open to a future marriage believed there was an ideal age to marry. Such beliefs could influence their dating attitudes and behavior. Only 30% said yes, there is an ideal age to marry. So, most young adults do not subscribe to an ideal age for marriage. Of those who do subscribe to an ideal age to marry, however, 30 was by far the age most nominated. Younger male respondents (< 27) said that 29 was the ideal for marriage, while younger female respondents said it was about 28. Older male respondents (>27) said that 30–31 was the ideal age, while older women said it was about 29–30. And even those who were older than 30 reported the ideal age of marriage close to 30. (Note that the ideal age for marriage was uncorrelated with indicators of religiosity and spirituality.)

The average age of first marriage is now approaching 30. Our findings suggest that contemporary young adults probably do not want this number to get any higher. At least for those who have an ideal age for marriage in mind, 29–31 seems to be the sweet spot. And it’s important to note that for a minority of young adults, their ideal age of marriage is already in the rearview mirror.

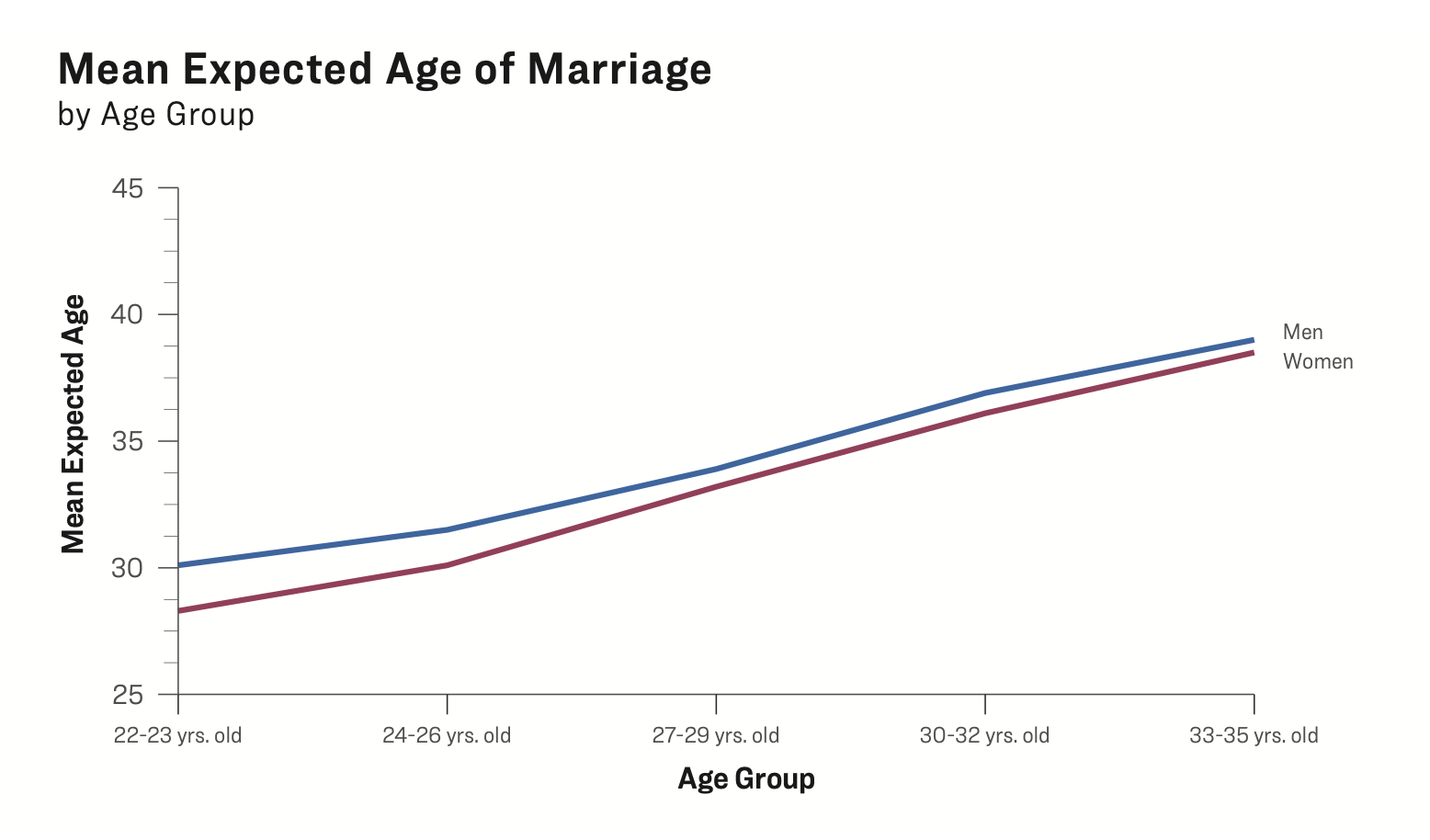

Age to Expect to Marry

We also asked respondents at what age they expected to marry, which also could shape dating behavior. The overall median age of expected marriage was 33 for women and almost 35 for men.16 But here age – and to a lesser extent, gender – mattered. For the youngest group (ages 22–23), their average expected age to marry was 28 for women and 30 for men. For 24–26-year-olds, their average expected age to marry was almost 30 for women and almost 32 for men. For 27–29-year-olds, it was 33 for women and 34 for men; for 30–32-year-olds, it was 36 for women and 37 for men. And for the oldest respondents (33–35), the average expected age to marry was about 39 for both women and men.

Except for the youngest women in our survey, the average expected age of marriage was at least 30 (even slightly higher than the current actual age at first marriage in the United States). And, importantly, note that regardless of current age, respondents’ marital horizon – the temporal distance between now and the age they expect to marry – was about 5–6 years in the future (Mall = 5.6; Mwomen = 5.2; Mmen = 6.0). So, the age they expect to marry is not fixed: it appears to slide upward as they get older rather than shrink with the passage of time. As a result, young adult dating lives are temporally disconnected from marriage expectations and may be only abstractly associated with the idea of marriage. (Note that for 1%–2% of respondents, their marital horizon was negative – they were already older than their expected age of marriage.)

Marital Salience

Given this temporal disconnect between dating and the expected age for marriage, we probed specifically for how prominent or salient the idea of marriage was for our survey respondents. We asked them five questions about the importance of marriage for them personally, which created a marital salience scale. We found that marital salience was moderate with this sample of young adults. The average rating was 3.3 (on a 6-point scale), although those who said “maybe/don’t know” about expecting to marry in the future were significantly lower on the scale than those who said “yes.” Interestingly, the level of marital salience did not differ by age groups. That is, older respondents reported the same levels of marital salience as younger respondents, so the personal importance of marriage to our respondents was independent of their age.

Still, a look at some of the individual items in this marital salience scale finds that nearly two-thirds (64%) reported that marriage was an important life goal for them, although less than half (47%) said marriage was a top priority for them at this time in their life. (Younger and older respondents were not significantly different on this item.) Nearly half (46%) reported that they would like to be married now. So, for a large minority of young adults, marriage may be a more proximate aspiration than the average marital salience score would suggest.

Findings: Dating Experiences and Attitudes

Now we shift to explore young adults’ dating experiences and attitudes. Note that 11% (n = 493) of our respondents reported that they were living together with a romantic partner and another 3% (n = 133) were engaged to be married. For these individuals, dating is qualitatively different than for other singles; they are focused exclusively on a committed partner rather than exploring other potential romantic partnerships. Because of this, we excluded cohabitors and engaged individuals from our analyses of many of the dating experience questions below. (And again, our analyses exclude survey respondents who do not expect to marry.)

Dating Experience, Frequency, and Satisfaction

Respondents reported a median of three exclusive romantic dating partners in their lifetime. Only 15% reported no exclusive dating partners. Another third (32%) reported 1–2 lifetime dating partners. But more than half (52%) have had significant dating experience in the past (three or more exclusive relationships) and we found few gender differences in this reported experience.

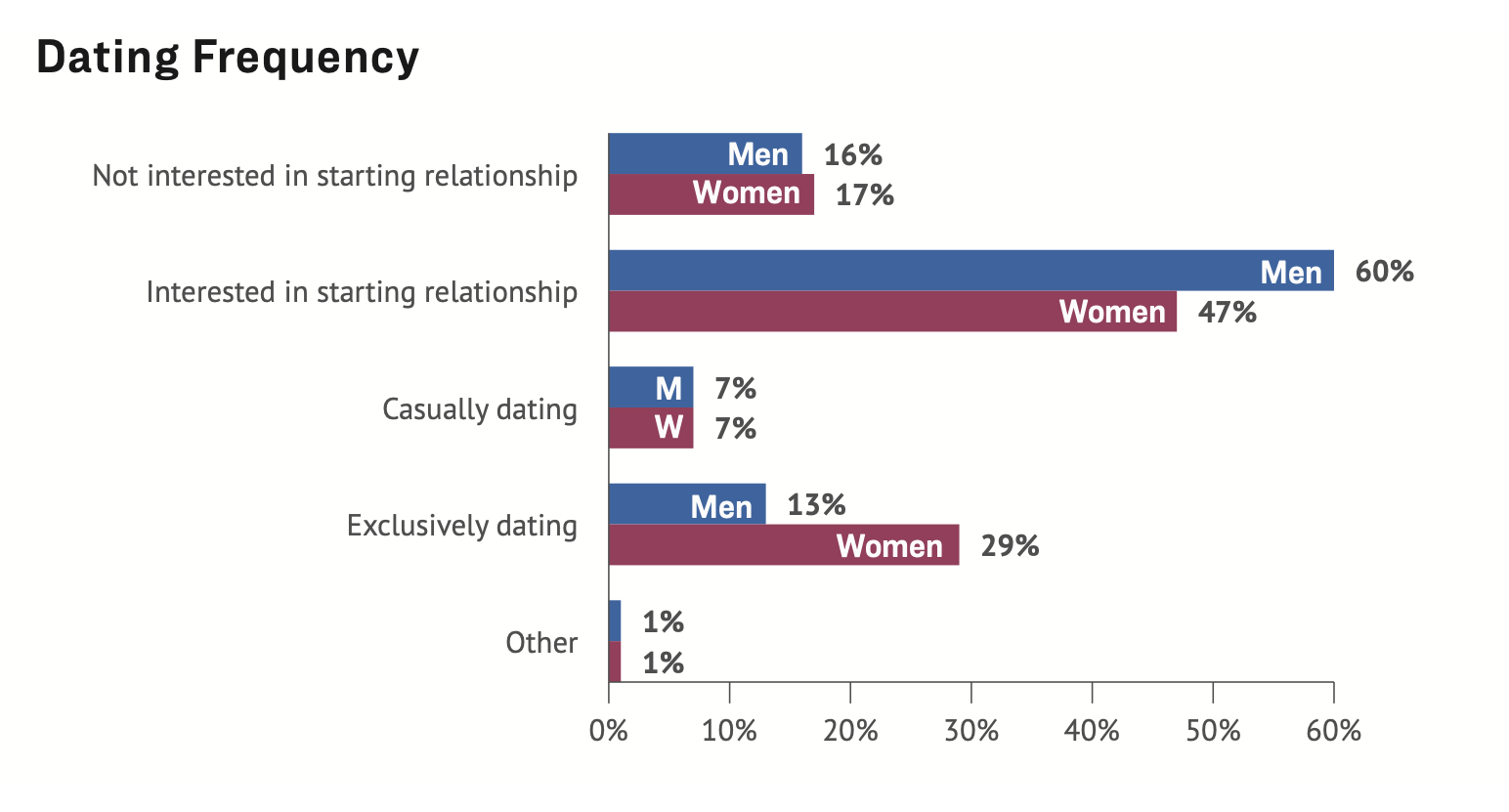

However, at the time of the survey, only about 30% of our respondents reported that they were dating, either casually or exclusively. About half (51%) of our respondents reported they were single but interested in starting a relationship, although this was much more the case for men (60%) than for women (47%). Only about one in six of both women and men reported being single but not interested in starting a relationship. Accordingly, dating is clearly a salient element of their lives – either behaviorally or cognitively – for a strong majority of our respondents.

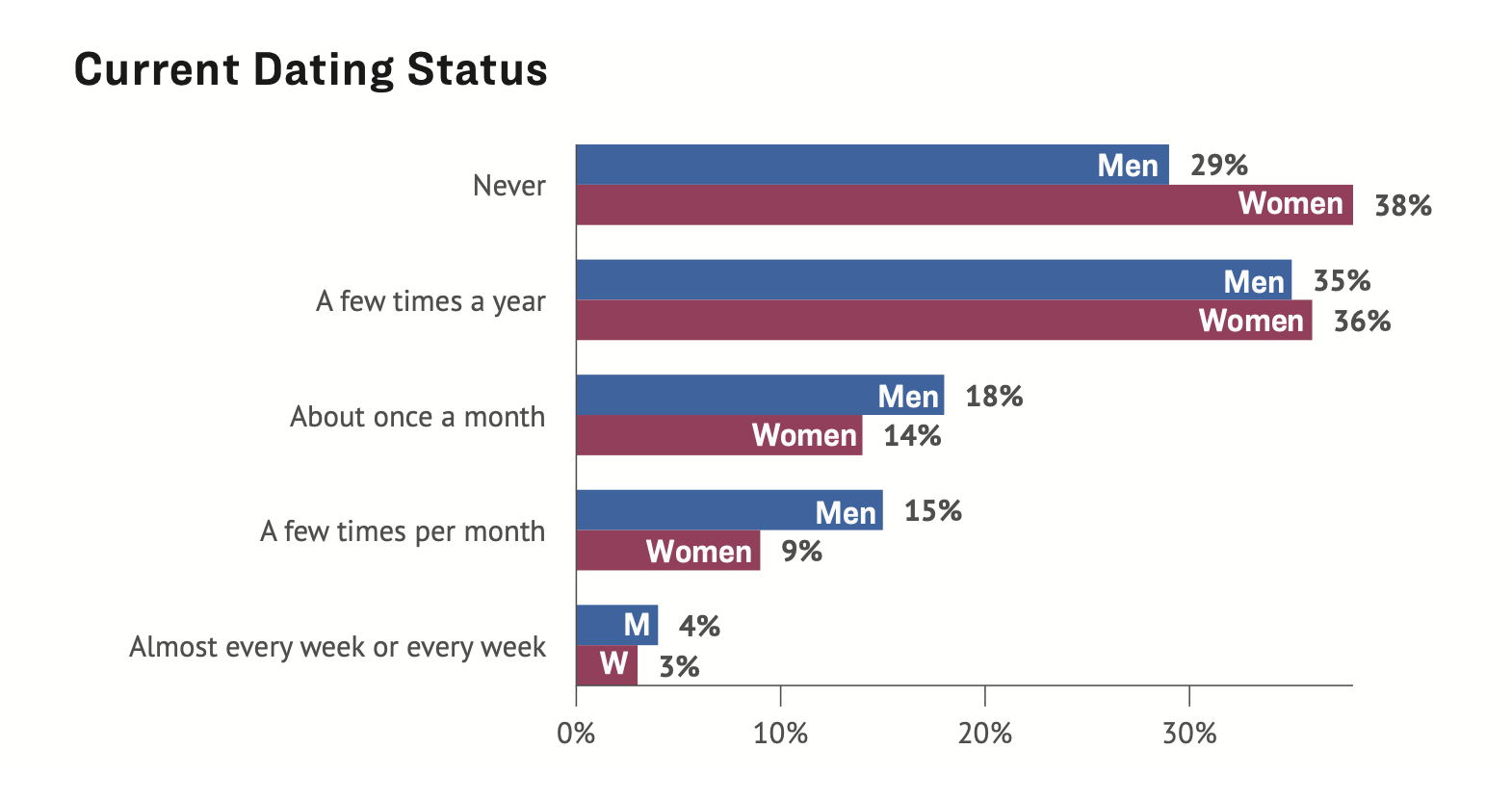

We also asked how often they were dating. Nearly threequarters of women (74%) and nearly two-thirds of men (64%) in our survey reported they had not dated or dated only a few times in the last year. Only 31% of these young adults – a quarter of women (26%) and a little more than a third of men (36%) – were active daters (dating once a month or more). Those who said they definitely expected to marry reported dating a little more often than those who said “maybe/don’t know.” (Interestingly, respondents in our survey who did not expect to marry (14%) reported the same low level of active dating.)

The frequency of dating could be related to their satisfaction with dating options, of course. Only 21% reported they were satisfied with their options. And 39% reported they were dissatisfied (with 30% neither satisfied nor dissatisfied). (Gender differences here were minimal.) However, dating frequency and satisfaction with options were only weakly correlated (r = .16, p < .001). Active daters had higher marital salience scores than less active daters, but the correlation was still weak (r = .16, p < .001).

Dating for contemporary young adults is infrequent, especially so for women. The relatively small proportion of young adults who are actively dating – and the general lack of satisfaction with dating options – lends support to the complaint we often hear from young people, that the dating system is broken.

Dating Confidence/Efficacy

Of course, low rates of dating would not be surprising if young adults lack confidence in their dating skills. Do they believe they have what it takes for dating? We might call this “dating efficacy.” We asked our sample to respond to a set of seven valuable dating skills. Overall, we found that dating efficacy was low; only about one in three respondents expressed much faith in their skills. (Those who said they definitely expected to marry scored a little higher on dating efficacy than those who said “maybe/don’t know.”) Only a quarter expressed confidence in the fundamental skill of being able to approach someone they were romantically interested in (men = 29%; women = 21%). A little over a third (37%) said they trusted their judgment when it comes to choosing a dating partner. They expressed similar levels of struggles with discussing their feelings with a dating partner (34%) and picking up on social cues on dates (36%). Thirty-eight percent were confident that they were attractive to potential dating partners (females = 37%; males = 39%). There was a small-to-medium, positive correlation between dating efficacy and dating frequency (r = .26, p < .001).

In addition, only about a quarter (28%) reported being able to stay positive after a bad date or relationship setback. A subsequent set of questions in our survey about breakup experiences allowed us to dive a little deeper into this response. More than half (55%) agreed that their breakups have made them more reluctant to begin new romantic relationships. And nearly half (45%) agreed that they have passed up opportunities for new romantic relationships because of bad experiences from previous relationships. Also, more than a third (36%) agreed that they now end relationships too quickly to avoid the possible pain of bad breakups. (Gender differences in these responses were minimal. And we found no significant differences between those who said they definitely expected to marry and those who said “maybe/don’t know.”)

Our findings suggest that a large proportion of young adults lack confidence in their dating skills. So, it’s not surprising that few are regularly dating. Later, we return to this crucial point to explore how we might improve dating skills.

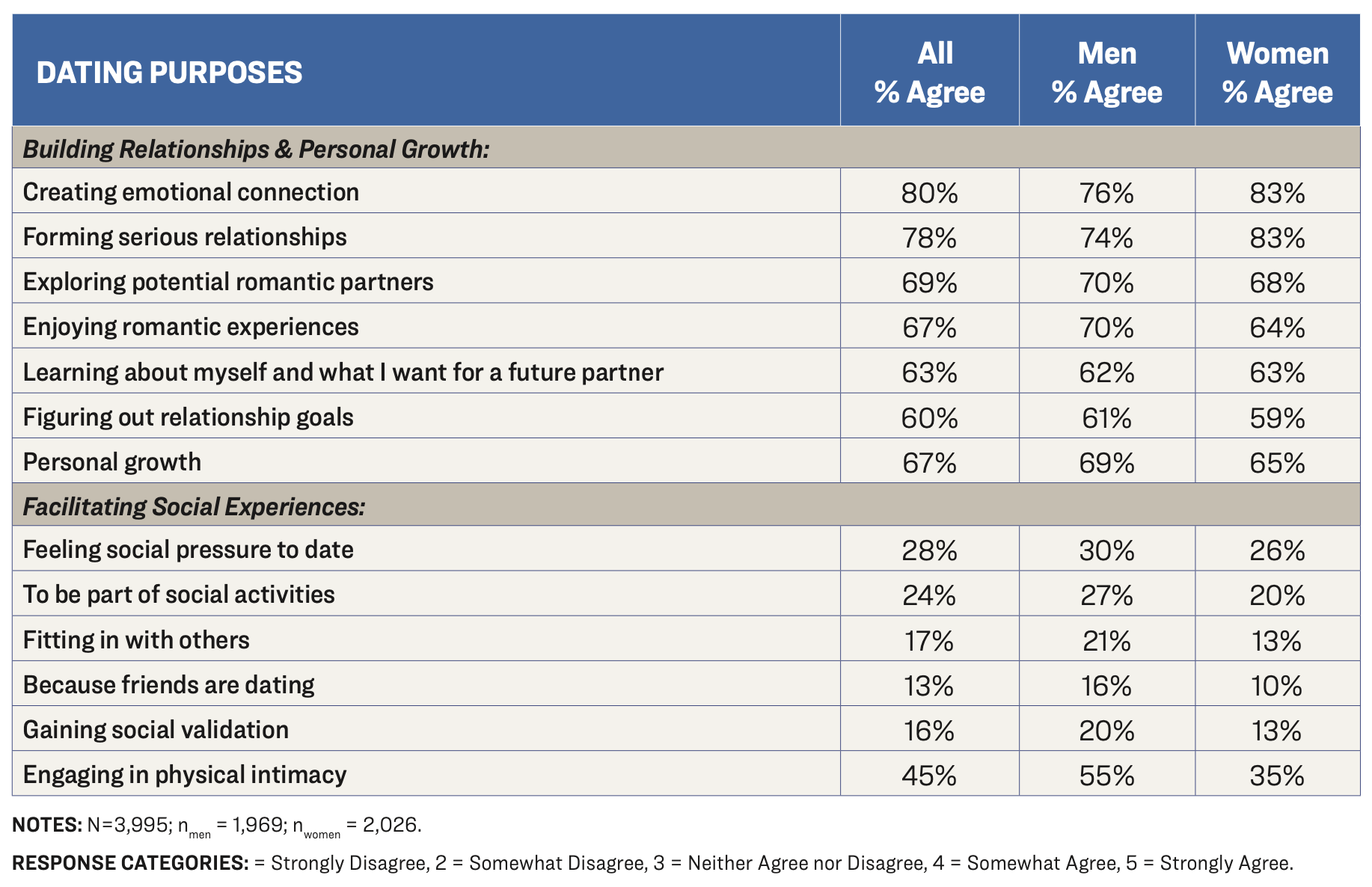

Dating Purposes

Even if dating is infrequent and their sense of dating efficacy is low, what reasons do young adults give for dating? We asked respondents to report on their purposes or intentions for dating. (Admittedly, for the many infrequent daters in our survey this may have been an abstract exercise.) The 14 items fell into two relatively distinct categories: (1) building relationships and personal growth; and (2) participating in social experiences. We found it noteworthy that the relational and growth purposes – which may be what we traditionally associate with young adult dating – were much more endorsed than the general social purposes (such as fitting in with others (17%), gaining social validation (16%), and being a part of social activities (24%)). Creating emotional connections was the highest rated purpose by both men and women (but was even higher for women: 83% vs. 76%.) A close second purpose for dating was forming serious relationships (78%). (Again, women rated this purpose higher: 83% vs. 74%.) Other purposes that were widely endorsed by both women and men were exploring potential romantic partners (69%); enjoying romantic experiences (69%); personal growth (67%); and learning about myself and what I want in a future partner (63%). Gender differences here were minimal. And somewhat surprisingly, our analyses surfaced few significant and meaningful age differences in dating purposes.

Dating frequency may be low, but young adults seem to want it for emotional connection, forming serious relationships, and enjoying romantic experiences. In an age of dramatic increases in loneliness and social isolation,25 young adults seem to yearn for the connection and relationship benefits of dating.

Engaging in physical intimacy (45%) was also endorsed as a purpose for dating, but it was unclear from the survey wording whether this served primarily a relational or just a social purpose. (Statistically, it leaned more toward just a social purpose.) Not surprisingly, engaging in physical intimacy as a purpose for dating produced the largest gender difference (males = 55%; females = 35%).

Young adults – both women and men, younger and older – in our survey strongly endorsed the more traditional purposes of dating to build serious romantic relationships and to explore self and learn and facilitate personal growth in those relationships. Perhaps many of their frustrations with dating stem in significant part from the gap between what their avowed purposes are for dating and their current capacities or skills for dating.

Barriers to Marriage and Dating

Feeling financially prepared to begin a marriage may be a significant reason that marriage for many young adults is well over the temporal horizon and dating seems disconnected from marriage. Most young adults in our survey agreed that you should achieve a certain financial threshold before marrying and that finances were a barrier to getting married (M = 4.3, SD = 1.02, 6-point scale). For instance, nearly 75% of our respondents agreed that “money and finances are a major barrier to getting married.” This was especially so for the younger respondents (ages 22–29). But we found no differences on this item between those who definitely expected to marry and those who said “maybe/don’t know.”

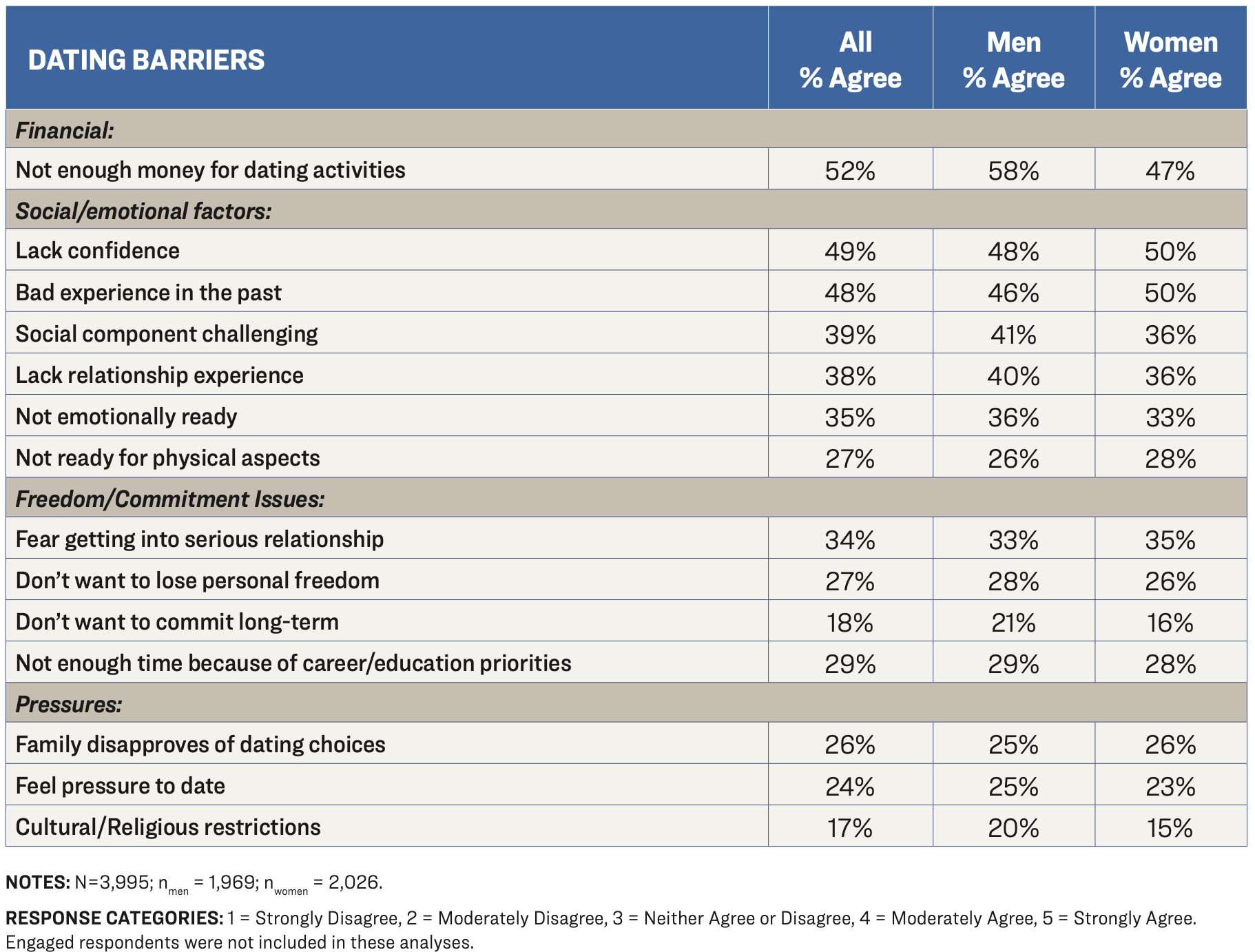

In addition, we asked respondents to tell us what specific barriers they experienced in their dating lives.

Interestingly, the biggest barrier to dating they expressed was not enough money, endorsed by more than half (52%) of respondents. This was more so for men (58%), but it was noteworthy for women, as well (46%). Dating for contemporary young adults has a price tag, and they feel the pinch. Money concerns are not just future-abstract in the sense of reaching a certain financial status to be able to marry; they are current-tangible about affording actual dates to explore serious relationships.

Respondents also frequently endorsed a set of social/emotional factors as barriers to dating. At the top of this list were lack of confidence (49%) and bad dating experiences in the past (48%). Echoing an earlier finding in this report, bad dating experience from the past was the most endorsed barrier for women (50%), and it was it was only a little lower for men (46%). Respondents also frequently endorsed lack of relationship experience (38%), not emotionally ready (35%), social component of dating difficult (38%), and not ready for the physical aspects of dating (27%).

Although there is a common notion that young adults want to avoid loss of personal freedom and commitment, we found that these potential barriers to dating were endorsed by relatively few young adults. For example, only a minority of young adults identified the fear of getting into a serious relationship (34%). And neither losing personal freedom (27%) or not wanting to commit long-term (18%) were significant barriers to dating. Gender differences in these dating barriers were minimal. (Those who said “maybe/don’t know” about getting married in the future compared to those who said they definitely expected to marry were a little more likely to report wanting to avoid long-term commitments in dating.)

So, few young adults express a fear of commitment and serious romantic relationships. But they lack dating confidence, worry about being emotionally ready or financially prepared for serious dating, and are inhibited by bad relationship experiences in the past.

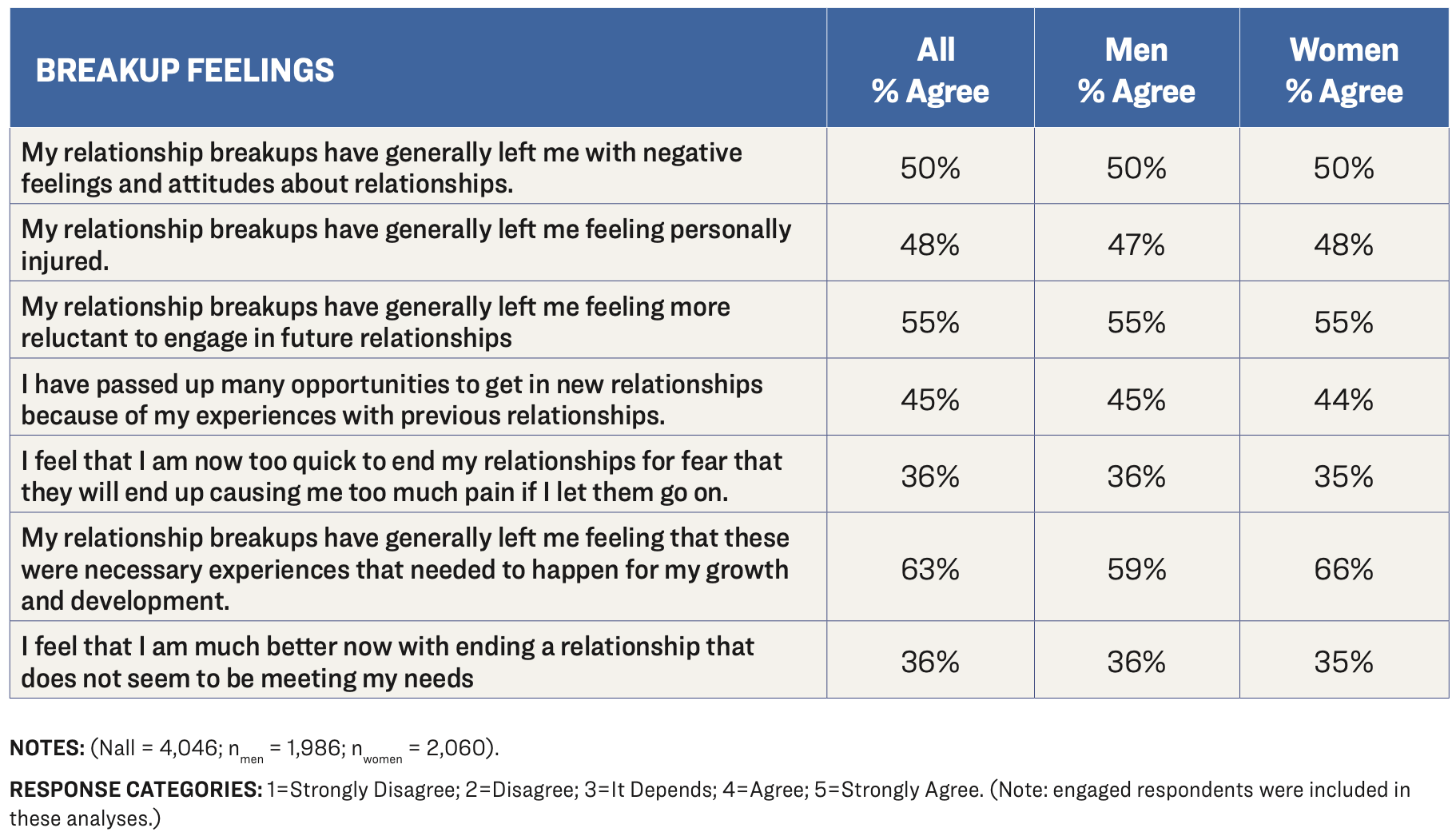

Breakup Feelings/Dating Resilience

We have already outlined a dating challenge that many respondents endorsed – dealing with past bad dating and relationship experiences. We explore that important finding in more depth in this section. We asked respondents a set of seven questions about their dating relationship breakups and how they affected their feelings about forming future romantic relationships. On the positive side, many agreed their relationship breakups were necessary and facilitated personal growth and development (63%) and that they are now better at ending relationships quicker when they do not meet their needs (67%).

On the negative side, however, half of both men and women agreed that their breakups left them with negative feelings about romantic relationships, and nearly half (48%) agreed that they felt personally injured by their breakups. Even more significantly, more than half (55%) agreed that their breakups have made them more reluctant to begin new romantic relationships. And nearly half (45%) agreed that they have passed up opportunities for new romantic relationships because of bad experiences from previous relationships. Also, more than a third (36%) agreed that they now end relationships too quickly to avoid the possible pain of bad breakups. (We did not find meaningful gender differences in these responses.)

Clearly, these young adults could use a boost in “dating resilience.” Breakups are an inevitable part of dating. Being able to absorb the losses and transmute them into productive learning is a fundamental dating skill.

Implications: Need for Dating Education

Young adults today are living in a depressed dating economy. A large majority expect to marry, but only a small proportion are actively dating. Regardless of their age, their marital horizon keeps sliding, remaining 5–6 years out. So, dating has only a distant connection to marriage and efforts to find a potential spouse are probably more of an abstract goal than a concrete objective for most. Still, a significant proportion would like to be married now. And these young adults endorse traditional purposes for dating – creating connection, forming serious relationships, exploring potential romantic partners and what they want in a future spouse – over dating just for fun or sex or social engagement. They yearn for connection and the benefits of healthy romantic relationships. But few report a sense of dating efficacy – a feeling of confidence in their dating skills, such as approaching people they are interested in, trusting their judgment about good dating partners, sharing emotions on dates, and – importantly – staying positive about dating and romantic relationships after a bad experience. Dating resilience is low. Almost half of young adults report they are more reluctant to date because of bad dating experiences in the past. And they encounter numerous barriers to dating, including the financial expenses, lacking experience and confidence, and not feeling emotionally ready. On a more optimistic note, only a small percentage of young men and women report that fear of commitment or serious relationships are dating barriers, contradicting a common cultural notion about young adults today. Finally, those who reported they definitely expect to marry compared to those who say “maybe/don’t know” date a little more often, have somewhat higher scores on dating confidence or efficacy, and have even less fear of commitment in dating.

There is a marital-expectations vs. dating-skills gap for most young adults today. How should we respond to this gap? How can we grow our way out of this dating recession if we want to increase the chances that young adults will form serious relationships that may lead to healthy marriages? We need a concerted effort to teach young adults healthy dating skills, something that receives little attention from the general culture or even the relationship education field. While the professional field of relationship education is admirably dedicated to helping couples form and sustain healthy marriages, it has not given enough attention to the dating experiences of young adults – the onramps to marriage. Our young adults need effective road maps that guide them to and through the dating experiences that will connect their marital expectations to actual unions.

Accordingly, one straightforward implication of the findings from our study is that young adults could use some basic help in building dating skills. Their desires and attitudes are not the problem. They want to build real human connections, form serious relationships, explore what they want in a future long-term partner, and desire the personal growth that comes from forming serious romantic relationships. And contrary to common beliefs, most are not afraid of commitment or losing personal freedom, and few fear that dating will interfere with their educational and career plans.

Nevertheless, few are regularly dating. They report being unprepared and having a low sense of dating efficacy. They lack experience, social and emotional confidence, and need to stretch their basic social skills. They struggle to know how to express their interest to a potential dating partner and to communicate effectively on a date. Also, they are discouraged by the cost of dating.

Yet these are hardly unsurmountable barriers. Motivated young adults can learn dating skills, how to approach partners they are interested in, how to improve their ability to make smart dating choices, and how to improve their general communication skills for dating. But relationship educators – who do so much to provide basic relationship literacy to teens, marriage preparation classes for engaged couples, ongoing marital enrichment workshops for married couples, and even intensive retreats for struggling couples thinking about divorce – need to develop a new niche – dating education. Generic relationship skills education does not sufficiently address the A-B-C’s of how to date. Parents, schools, churches, media, and the general culture are not meeting a clear need.

Relationship educators could consider offering creative dating “bootcamps” for young adults who need skill practice and confidence boosts, systematically addressing the pragmatic skill deficits and confidence arrears identified in our survey. And given the digital natives that are their prime target audience, they will likely have greater success with online educational offerings, like the “DatingREADY” e-course offered by the Utah Marriage Commission.30

However, this TikTok generation may not sit still for traditional didactic curricular programs (in-person or online), which have been the bread-and-butter of relationship education. Dating educators may need to grab young minds with engaging “infotainment” on digital platforms to reach their audience. And pragmatics will be as important as principles, we think. Relationship educators will need to provide opportunities not just to listen and learn but to practice and improve. We also suspect that “peer educators” will be more effective as instructors than older adults who experienced a very different dating regime than their students.

In addition, we think this dating education “space” is ripe for creative, hands-on approaches. We have been impressed with a few efforts to provide structured dating opportunities infused with skills education. One colleague we know sponsors carefully constructed speed dating events for young adults who are struggling with knowing how to date or just overcoming the inertia of interminable scrolling. The primary purpose of these structured dating events is to teach skills and then break inertia – to get young adults learning, practicing, and dating. Success is not necessarily associated with continued dating, although there is a good deal of that too.

Whatever approach relationship educators take to help young adults improve their dating skills and opportunities, we recommend including training on how to deal with bad dating experiences and painful breakups. Our survey revealed that bad dating and relationship experiences in the past were one of the biggest barriers to current dating. Dating life brings hurt, heartbreak, rejection, confusion, and body blows to confidence. And this comes on top of this generation’s well-documented mental-health challenges. These bad experiences make them less likely to pursue relationships in the future because they are in recovery mode. Relationship educators should anticipate that their students need help building dating resilience, including understanding what went wrong in past relationships, normalizing the experience, healing from the pain, overcoming fear of being hurt or rejected again, building grit, making intentional plans going forward, etc.

Given relationship education’s prevention orientation, educators could be doing more to steel young adults against these inevitable painful experiences so that they don’t result in foreclosing on the dating scene during their prime dating years.

And there is an important practical matter too – the cost of dating was also a big barrier (reported by both women and men). Perhaps relationship educators could help young adults get around this challenge by providing lists of creative dating options with cheaper price tags. Creative social media influencers undoubtedly could help with this. Maybe they can help shift the general dating culture so that an average date is defined not as a formal activity that requires a large financial outlay – such as a dinner for two at a nice restaurant and tickets to a concert – but as simply a time and place to pair off, talk, and get to know someone better, enjoy opportunities for fun interaction, share life stories and future aspirations, etc. In other words, dating should be oriented more to its relational and personal growth purposes that young adults strongly endorse and less to its general social purposes that they are less enthusiastic about.

One final comment here for dating educators regarding finances. Given young adults’ current money constraints and their future financial worries, dating education probably will need to be more akin to a public service than a gainful enterprise. Dating education will need generous sponsors and institutional supporters as much as talented social entrepreneurs.

Note that dating education for young adults will not need to differentiate much based on gender. Our survey revealed overall remarkable similarity of dating experience and challenges for women and men, at least as far as we probed. And this would be a fascinating area for further exploration and research.

A final reflection on the 5–6-year marital horizon we observed in this survey regardless of respondents’ age:

With this temporal distance, it will be hard to create a stronger connection between the present act of dating and the future expectation of marriage for young adults. To some extent, perhaps we don’t need to be overly anxious about this. If we stimulate the dating economy and give young adults the skills they need to prosper in this challenging market, then more dating should lead to more serious relationships that will, in turn, spur more thoughts about marriage and more decisions to tie the knot. Still, it would be wise for relationship educators, as they build learning opportunities for healthy dating, not to present dating in maritally neutral terms. There is a teleology to dating. The institution of marriage needs a robust dating system to bring couples to the altar. And recall our findings that, regardless of age, nearly half of young adults say they would like to be married now. Dating educators should keep these findings in mind. And at a minimum, they should help daters be more aware and intentional, to be cognizant of their short-, medium-, and long-term purposes for dating, to inquire about these things of their dating partners, and to align couple purposes and plans – especially regarding marriage.

Recommendations for Relationship Educators Teaching Dating Skills

Generic relationship skills education does not sufficiently address the A-B-C’s of how to date. Professional and lay relationship educators need to pay more attention to this educational void for young adults. Here are several concrete recommendations for effective dating skills education.

- Offer creative dating “bootcamps” for young adults who need skill practice and confidence boosts. Include sufficient practice time.

- Prioritize online platforms.

- Grab young TikTok eyes and minds with engaging “infotainment” rather than traditional didactic instruction.

- Make dating skills education low- or no-cost. Find financial supports to offset instructional costs.

- Consider using peer educators who understand better the contemporary dating environment.

- Build greater dating resilience by including preventative training on how to deal with bad dating experiences and painful breakups.

- Include lists of creative dating options with cheaper price tags to avoid the sticker shock of dating.

- Understand that differences in dating experiences for women and men are minimal; there is little need to accentuate gender differences in instruction.

- Reconnect dating and marital goals; gently remind young adult participants of the connection of dating to their expectations and aspirations for marriage.

We acknowledge that we have not covered in this study the full range of issues that impact the contemporary dating landscape. For instance, we did not explore in our survey how AI and the new world of AI companions may be impacting young adult dating lives. Nor did our survey differentiate between distinct dating types or the longitudinal course of dating – how casual dating grows into more serious dating and progresses to committed, exclusive dating, and even engagement. Our focus was primarily on the early stages of dating, on initiating relationships that may eventually develop into long-term unions. We hope this study can spur more research to better understand young adult dating.

Moreover, we acknowledge that our focus here has been on individual behavior and personal experiences of dating. And as such, we have explored how relationship education efforts could help to improve young adults’ dating lives. In this focus, however, we acknowledge that young adults are embedded in broader cultural and social systems that also influence their dating experiences. Our recommendations for educational efforts do not diminish the need for broader cultural and policy responses to improve the dating economy. For instance, worries about the “marriageability” of men lead some to believe that the marriage pool is too shallow to accommodate many women’s aspirations for marriage. To the extent this is true – or women perceive it to be true – this would likely reduce dating and sour dating experiences. Broad social efforts to improve men’s marriageability should improve the dating landscape. Nor have we explored directly how the growing ideological and political divide between young men and women may be impacting the dating scene. Also, we believe that young adult dating lives will be impacted positively by public actions to reduce the cost barriers to marital formation, such as employment barriers, higher education costs, and unaffordable housing. More directly, public funds now being allocated by the federal Administration for Children and Families to provide relationship education to help couples form and sustain healthy marriages could expand their reach to include healthy dating skills education (which they currently do not allow).

Nevertheless, we emphasized in this report a more immediate stimulus for the current dating recession in the form of attention to a new kind of relationship education: dating education. Many of the challenges young adults face in their dating lives can be surmounted with better knowledge and concrete skills. We are optimistic that talented relationship educators will rise to fill this void, assisted by parents, social media influencers, religious leaders, and others. The alternative, we believe, is an ongoing dating recession that will depress future marriage rates and all the known benefits of healthy marriages for adults, their children, and their communities.

This dating recession is more than just another instrumental challenge facing young adults today. Their lack of dating experiences is a deficit of connections – connections that prime their souls for one of the richest experiences humans can have – romantic love. So, young adults risk more than they know when they are not falling in (and out) of love during this formative time of life.

The New York Times columnist David Brooks describes this risk well recalling his first real love affair in his late teens and early adulthood:

I was transformed by my time in college classrooms, but that love affair might still have been the most important educational experience of my youth. It taught me that there are emotions more joyous and more painful than I ever knew existed. It taught me what it’s like when the self gets decentered and things most precious to you are in another. I even learned a few things about the complex art of being close to another. . . . We all need energy sources to power us through life, and love is the most powerful energy source known to humans.

Editor's Note: For a footnoted copy of this report, as well as the latest Social Indicators of Marital Health and Well-Being, download the full report here.