Highlights

- Women who travel more report larger gaps between the number of children they say would make them happiest, and the number they have. Post This

- The rate at which women progress from being childless to their first birth declined by 28% between 2007 and 2023. Post This

- Travel is not just a signal of income, even within income groups; it’s correlated with other kinds of status indicators. Post This

Birth rates are falling around the world. While generous pronatal policies to support families are a tried-and-true strategy to modestly increase birth rates, the rather smallish effects have led most people to conclude that there must be important cultural headwinds at play. Identifying exactly what those headwinds are is more challenging. But one factor weighing on fertility may be staring us in the face as we get back to work: travel.

Globalization and the internet have completely redrawn the travel landscape. In almost every country, annual tourism visits have increased over the last several decades. Global airline traffic has exploded, even as the inflation-adjusted price of tickets has fallen. AirBnB, TripAdvisor, Uber, and other apps like these, have dramatically lowered the barriers to international travel, as a would-be traveler can book extended vacations at ease from home. The rise of travel can be seen easily in American data: the share of Americans with active passports has risen from about 6% in the 1970s to 54% today, and 2025 saw one of the biggest jumps on record. Between 1990 and 2024, the number of international passenger departures from the U.S. rose from 0.34 per U.S. resident to 0.76—a near-doubling of international travel in a generation. The data shows up in spending too: airplane tickets rose from 0.2% of U.S. consumer spending in 1959, to 0.95% in 2024, even as inflation-adjusted prices fell.

The cultural shift towards Instagram-able vacation destinations may bear some share of the blame for global demographic decline.

But could travel be impacting family life? Secretary Duffy at the Department of Transportation certainly thinks so, as he recently announced an initiative to make airports more family-friendly. Likewise, now-Vice President JD Vance worried about this topic in a viral committee hearing, urging the Biden Administration not to increase prices for children on flights.

As it happens, we have data on fertility and international travel that reveals that the rise of travel (and in particular air travel) as a widespread recreational activity probably is impacting birth rates. Because the rise of airborne tourism is a global phenomenon, the cultural shift towards Instagram-able vacation destinations may bear some share of the blame for global demographic decline.

Who Travels?

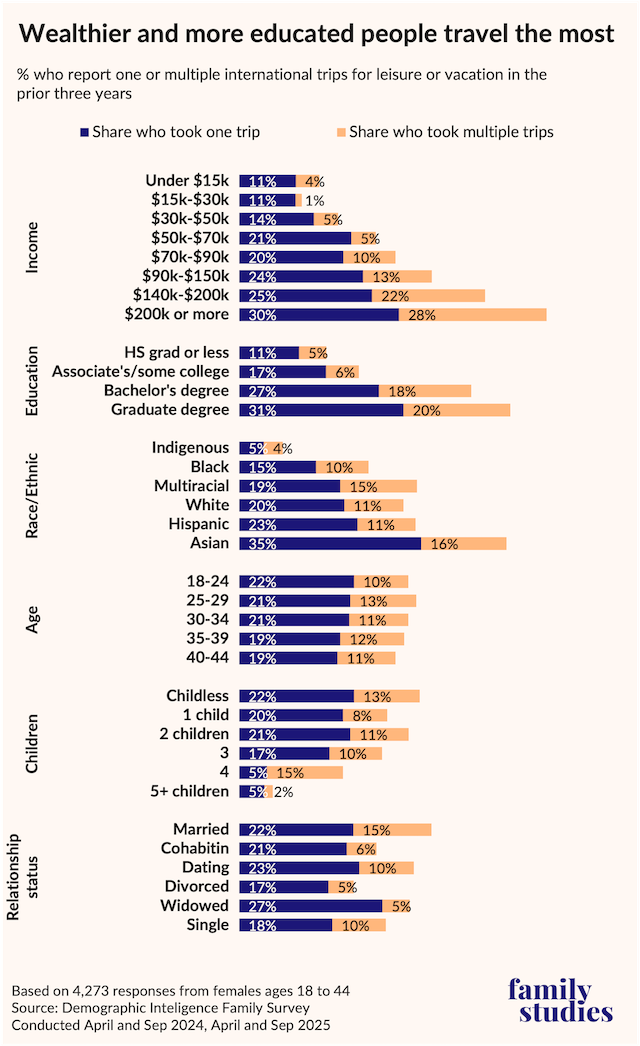

In several rounds of the Demographic Intelligence Family Survey conducted in 2024-2025, we asked respondents (U.S.-resident females ages 18 to 44) if they had traveled abroad in the prior three years. Of the 4,273 valid respondents who answered this question, about 700 had taken one foreign trip, and almost 400 had taken multiple trips.

Who travels isn’t a big surprise. The richer a woman’s household, the likelier she is to travel. Likewise, more educated women are also more likely to travel.

These differences in travel across socioeconomic status explain much of the racial and relationship status variation in travel. However, Hispanic and Asian respondents still have higher rates of international travel, likely because many of these respondents may have been visiting friends or relatives back home.

It should be noted that education and income have independent, separate effects: graduate-educated women travel more than bachelor’s degree-holding women who have the same income, and bachelor’s degree-holding women travel more than associate’s degree-holding women of the same income, etc. Thus, travel is not just a signal of income, even within income groups; it’s correlated with other kinds of status indicators.

It's also noteworthy that there are differences in travel across family statuses. Married people travel the most, though after removing the effects of income and education, married and single people have similar travel propensities.

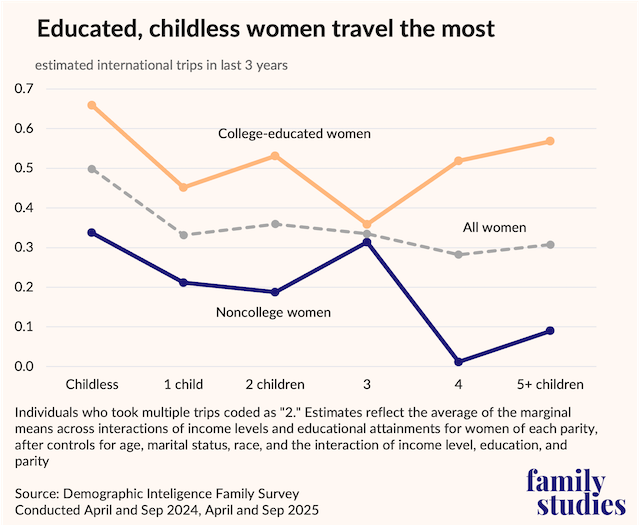

But people with children travel less. The descriptive statistics shown above clearly show that women with 3+ children travel less, but adding appropriate interactions by income and education, as well as controls for race, age, and marital status, makes the effect even clearer.

For women of the identical income and educational level, after controlling for their race, marital status, and age, having children is associated with about a 1/3 decline in travel. Most of this effect manifests at the first birth, though there is some ongoing decline beyond the second birth as well.

Thus, even as Americans are traveling more, and as international travel appears to be strongly associated with social class and social status, a stark reality confronts potential parents: when you have kids, you travel less. And, since international travel is a strong signal of social status, having children creates an automatic downgrade in social status. This is an example of how a specific cultural norm (widespread high-status international leisure travel) might directly influence concrete fertility choices.

Travel Norms Might Reduce Marriage

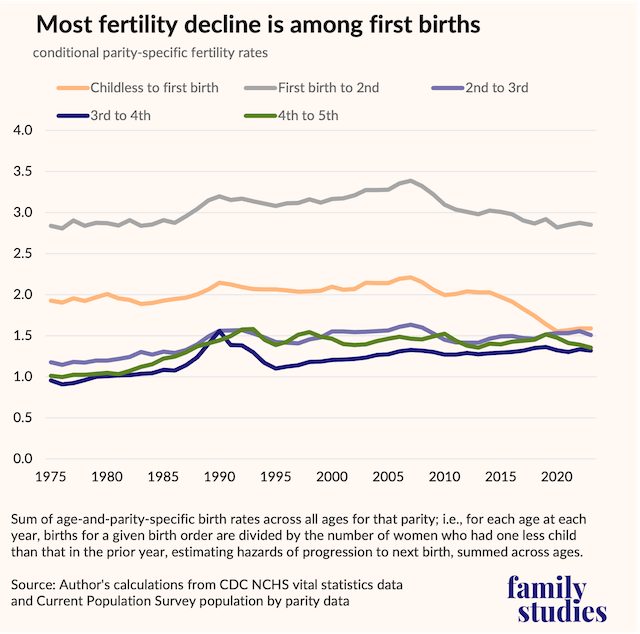

But is this effect mechanism plausible? To start with, we might ask, “Has the decline in births in America mostly been first births or higher parity births?”

Essentially, there has been no decline in the rate at which American women with two children go on to have third or fourth child. Since 2007, there has been a modest decline in the rate at which women with one child have a second, though rates remain comparable to the 1970s and 1980s. Where U.S. fertility has truly broken new ground is on the progression from childlessness to first birth. The rate at which women progress from being childless to their first birth declined by 28% between 2007 and 2023.

On its face, then, the rise of leisure travel could possibly explain the unique rise in childlessness. But here at IFS, we have repeatedly argued that rising childlessness is mostly driven by falling marriage, and I just showed above that marital status doesn’t predict travel. However, while individual level travel might not predict individual level marriage, society-wide changes in travel could cause society-wide changes in marriage.

Most notably, if men and women have very different views or experiences of travel, this could influence how easily men and women pair up. If women see travel as an important form of identity-formation, a high-status activity, and a valuable form of leisure, but men disagree, then women and men might find themselves at odds over what activities they enjoy together, or that they have fundamentally divergent experiences of the world. Men who are unwilling to travel might even inadvertently broadcast to women that they have low social status. As it turns out, voluminous survey data suggest women really do value international travel more than men, and that women make up a disproportionate share of those traveling internationally for leisure. For whatever reason, international leisure travel is a disproportionately feminine activity, and one that women tend to see as part of their identity formation and growth.

Unfortunately, we didn’t explicitly ask respondents if travel was a reason they weren’t having children in any of our surveys (a gap we will rectify in 2026). But we did ask respondents a related question—whether their family decisions had been shaped by a desire “to maintain leisure time and personal freedom.” As it happens, answers to this question predicted actual travel behavior:

Among childless women, reporting that family decisions had been impacted by a desire to maintain leisure time and freedom very strongly predicts travel behavior. With controls for income and education, the effect size is smaller. Thus, to the extent that there has been a growing cultural norm toward more autonomy from any inconvenience, travel may be an important part of that change.

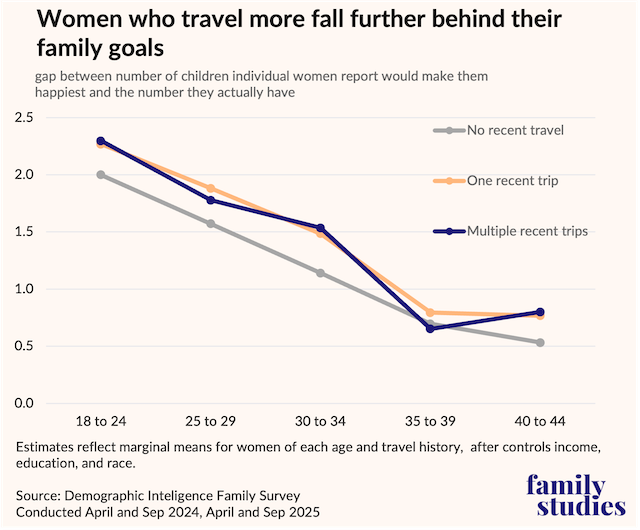

More directly, women who travel more do report larger gaps between the number of children they say would make them happiest, and the number they have.

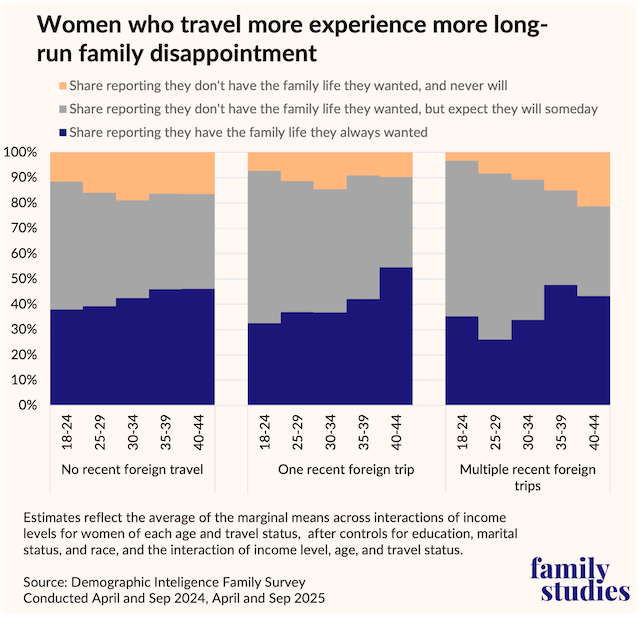

Nor is this a neutral result for women’s own sense of well-being. We also asked respondents if their family life had achieved what they hoped it would, or if they expected they’d never have the family they had wished for (as well as a neutral option).

When women are under 30, those taking multiple foreign trips per year are the least likely to report bad family outcomes—but by ages 40-44, women taking multiple trips per year are the most likely to report bad family outcomes. At almost every age, women reporting multiple trips per year have the lowest odds of reporting the best family outcomes. Among women who take no or just one trip per year, their good family outcomes rise, while their bad outcomes are fairly stable. But for the globetrotters, results are more mixed, and bad outcomes rise persistently.

Obviously, reverse causality could be a factor here: older unmarried, childless women may be more likely to travel internationally because, without the duties of parenthood, they have more time and money! But while this kind of selection effect does challenge the view that travel is intrinsically less rewarding than women think, it actually suggests the possibility that travel is a high status good, and people whose family hopes have been disappointed (especially older childless women) disproportionately steer public narratives and imagery around travel. Thus, travel becomes a conduit for comparatively negative or disappointed views of family life to permeate the culture.

Should Families Travel?

The rise of international travel as an “achievable status good,” especially for women, is likely impacting fertility. Young people correctly anticipate that having kids will make travel harder, more costly, and less frequent, and, as such, they see “less travel” as a cost of having kids. But because travel is strongly associated with high socioeconomic status and other reputational goods, “less travel” is not simply a loss of leisure; it’s quite literally a loss of social status and self-worth for many young Americans. As Americans age, women with disappointed family aspirations come to make up a larger share of travel and travel spending, leading tourism destinations and travel promoters to promote a less family-friendly experience. This, in turn, makes travel more challenging for families, and the cycle repeats.

It's tempting to suggest that the solution here is for pronatalists to counterprogram luxury travel: promote a norm of being happy staying home, taking few or modest vacations, and refusing to endorse the status gains from travel. Unfortunately, that strategy is probably doomed to failure for at least two reasons.

First, international travel is fun for most people! Trying to convince people that fun things aren’t fun is not a strategy with a long track record of success. Moreover, big families who can afford to travel still travel a lot: it’s just a lie to promote the idea that more kids replace the enjoyment of travel, since the travel propensities rise with income even among big families. Pronatalists should freely admit that it’s fun to go to Italy.

Second, the underlying reason international travel has expanded is because of technological, political, and economic shifts: the Cold War ended, the internet made planning easy, innovation and deregulation made flights cheaper, globalized business gave many business travelers a taste of destinations for leisure, etc. None of these trends are going away. Without an actual structural economic reason to shift the economic balance in favor of staying home, the airport will continue to defeat the maternity ward.

Family-Friendly Travel

The more rational approach is to make travel more family-friendly. My family—which consists of me, my wife, and our 4 children ranging in ages from 6 to 3 months—loves to travel. We traveled to Asia for three weeks last year with another family of small children, and we had a blast—and we’re intimately familiar with the challenges of family travel.

The Department of Transportation could increase the social status and desirability of family life, and thus support American birth rates, by making a range of tweaks to travel (some of these are already envisioned in Sec. Duffy’s recent plan rollout, an encouraging sign):

- Require all airports to provide separate lines at security, customs, and immigration for families with small children. Most countries outside the U.S. already do this.

- Adjust early boarding rules from their current status as “common courtesy” to actual regulatory requirements. Families with children should always board early.

- Require airlines to guarantee seating together for families with children regardless of class of ticket purchase, provided all tickets are of the same class.

- Waive all federally-charged excise taxes and TSA security fees for children under age 12.

- Provide an incentive system to encourage airlines to increase the number of bassinets on airplanes, and for airports to build more playgrounds within their premises.

- Allocate funds for the Department of State to automatically expedite all passport applications and renewals for minors.

- If all parents traveling with children have a preclearance status such as Global Entry or Nexus, automatically apply that status to all accompanying children under age 12.

- Impose a new federal excise tax on any seat with a length X width area of 75% more than the average seat on that flight.

- Use DOT funds to make all luggage trolleys free in all U.S. airports, as they are in most airports around the world.

- Publish an annual family scorecard of airports and airlines, ranking them on a range of family-travel attributes, in order to notify travelers about quality of service.

Rather than try to roll back the clock on travel, the Department of Transportation should take concerted action to make travel cheaper, smoother, and more accessible for families. Doing so would help increase the ability of families to access an emerging high-status good in American society.

Lyman Stone is a Senior Fellow and Director of the Pronatalism Initiative at the Institute for Family Studies. He is also the Director of Research at the consulting firm Demographic Intelligence.

*Photo credit: Shutterstock