Highlights

Is it possible to enact pro-family tax reform? As pressure to expand the child tax credit (CTC) intensifies, it has become apparent that tax reform is really impossible unless it includes pro-family reforms. While many pundits and policymakers find this surprising, a closer look reveals that pro-family considerations were central to the 1986 tax reforms, which saw the dependent exemption doubled and indexed for inflation. The story of how and why these changes were made to the dependent exemption in 1986 offer lessons for reforming the child tax credit in 2017.

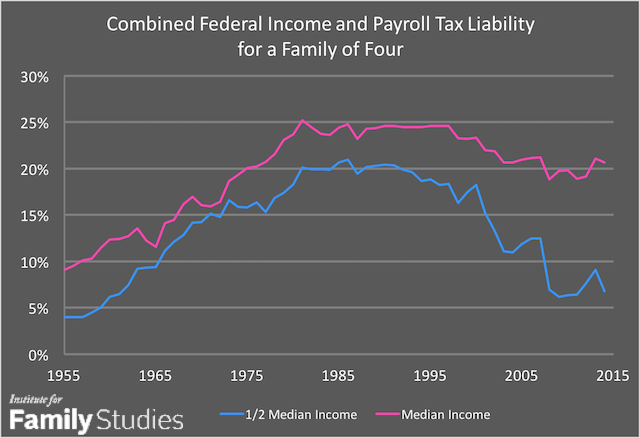

The story begins with Eugene Steuerle, an economist in the Tax Analysis Division of the U.S. Treasury. In 1981, the American Enterprise Institute held a one-day conference on “Taxing the Family” and tasked Steuerle with writing a paper on the tax treatment of families with children. Having never examined the data prior to this, Steuerle was amazed by what he found. Because personal exemptions were not indexed for inflation, their real value had declined by 50% between 1948 and 1981 despite nominal adjustments over the years. As a result, the tax burden on a married family with two children earning the median income jumped from 0.3% of their income in 1948 to 11.3% by 1981—an increase much higher than that for taxpayers without children.

The conference proceedings were eventually published in 1983. Steuerle’s findings, which were quickly picked up by the media, shocked the public. Based on this new data, an unlikely coalition of pro-family conservatives and anti-poverty liberals coalesced around a proposal to increase the dependent exemption as a way to reduce pressures on working and middle-class families. It directly led to the Reagan administration’s decision to double the dependent exemption as part of what would become the 1986 tax reforms. One of Reagan’s advisors later wrote to Steuerle:

Had I not read your paper… I would have missed what became the core argument for the family initiative which I had urged on the President, and which he adopted—and there never would have been a Presidential decision to double the personal exemption in the tax code. Regardless of the fate of the tax bill this fall, the tax exemption portion, I predict, will survive—and it’s all due to your insightful analysis.

Rather than assuage the coalition of pro-family and anti-poverty groups, the success of the 1986 expansion mobilized them to continue to work for family tax relief. They had stemmed the rising tax burden on families but had yet to reverse the trend. It was not until 1997 that they finally scored another victory with the introduction of a $500 child tax credit. Between 2001 and 2003, the Bush administration doubled the CTC to $1,000 and made it partially refundable for the first time. This change was crucial. Although the federal income tax burden was declining, family payroll tax burdens continued to climb, becoming the primary source of tax liability for most working-class families. Refundability helped reduce payroll tax burdens for families without income tax liabilities. Building on this, the Obama administration further reduced the refundability threshold, making more working-class families eligible for much-needed tax relief.

Source: Tax Policy Center, "Historical Combined Income and Employee Tax Rates for a Family of Four," 2015.

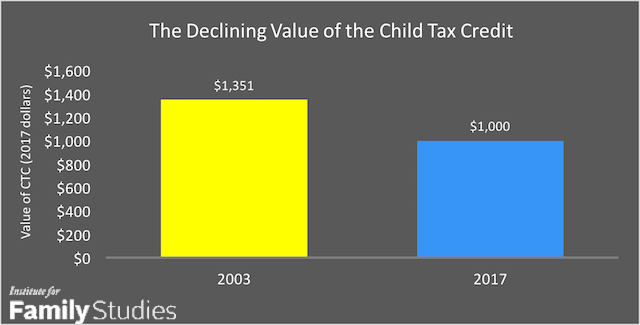

The bipartisan expansion of the child tax credit (CTC) has done a lot to provide relief to American families, but total tax burdens are still above the mid-century levels Steuerle used as a baseline. Among tax reformers, there is a debate about how much they would need to expand the CTC to make up for the loss of the dependent exemption. This is where Steuerle’s insights about choosing the appropriate baseline and accounting for the effects of inflation are critical. Because the CTC was not indexed when it was expanded in 2003, it has lost 25% of its value in real terms, as the figure below shows. Had it been indexed like the dependent exemption, it would be worth about $1,350 today. Additionally, according to the Department of Agriculture, the cost of raising children has increased 6-7% during this same period.

Source: Author’s calculation using CPI index

What are the implications? Proposals to eliminate the dependent exemption and increase the CTC from $1,000 to $1,500 would actually make most families worse off than they were in 2003. The loss of the dependent exemption, erosion of the child tax credit, and rising cost of raising children mean that policymakers need to increase the CTC closer to $2,500 if they want to ensure that middle-class families are better or no worse off.

Furthermore, it is imperative that policymakers continue the trend that started with the Bush administration of continuing to expand refundability to cover the payroll taxes falling most heavily on working-class families. As Robert Stein has argued, this would further reduce the anti-parenting bias built into Social Security and Medicare financing. Proposals to make the expanded portion of the CTC nonrefundable would leave these families high and dry.

Tax reform offers a once in a lifetime chance to make the tax code work for American families. Policymakers may be tempted to shortchange families in favor of other priorities but, as was the case in 1986, the data reveals what families are really owed in tax reform.

Joshua T. McCabe is a sociologist and assistant dean of social sciences at Endicott College.