Highlights

- Per a new study, “despite generous Danish social policies, family influence on important child outcomes in Denmark is about as strong as it is in the United States.” Post This

- Despite Denmark's aggressive efforts to equalize opportunity, richer parents still manage to give their kids a leg up: they sort into neighborhoods to live alongside each other, effectively hoarding their social capital. Post This

Those who advocate a bigger welfare state typically have two goals in mind. One, they want to redistribute money and resources to the less fortunate. And two, they want to facilitate economic mobility: If kids at the bottom are given more money, better schools, and so on, hopefully these investments will improve their chances of making it to the top.

A new paper from James J. Heckman and Rasmus Landersø, drawing on several other studies from the past few years, contends that Denmark—a country with a large welfare state that often serves as an inspiration for the American Left—succeeds in only the first of these goals. Redistributing income does, obviously, reduce inequality. Yet, the authors note, “despite generous Danish social policies, family influence on important child outcomes in Denmark is about as strong as it is in the United States.”

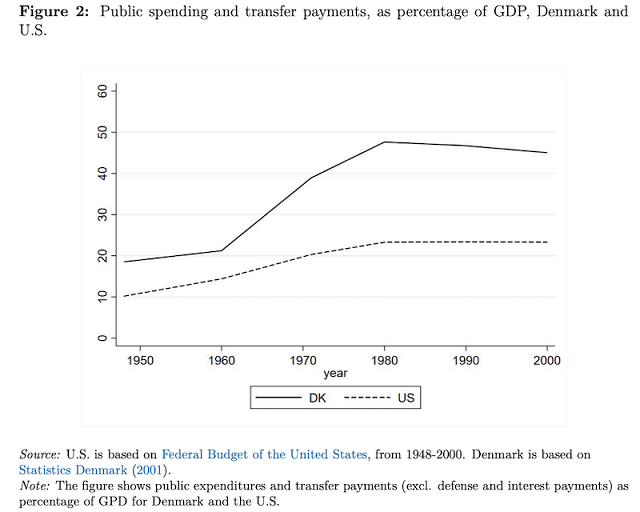

It would be hard to exaggerate the size of Denmark's welfare state. As this chart shows, its spending on its citizens has long been higher than that of the U.S. (relative to its GDP, which is slightly lower). The gap especially opened up in the 1960s and 1970s, when Denmark enacted universal health care, universal child care, and universal pensions for the elderly. Denmark even has free college.

Source: Heckman, J., Landersø, R., "Lessons from Denmark About Inequality and Social Mobility," NBER Working Papers, March 2021.

All this spending does contribute to the fact that inequality in Denmark is relatively low. The World Bank puts the “Gini” index, one measure of income inequality, at about 28 for Denmark and 41 for the U.S. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development reports that 6% of Denmark’s population lives on less than half the country’s median income, just one-third of the figure in the U.S.

But what about mobility?

Measuring income mobility in one country is hard, and comparing countries is even harder. For example, traditional studies rely on just a “snapshot” of income data from parents and kids, meaning short-term income fluctuations can throw off the results. Income mobility in Denmark, it turns out, is much lower when lifetime incomes are measured more thoroughly, which is possible in part thanks to the country’s “register” of data on its population. Good international comparisons of raw income mobility remain difficult until more studies, from more countries, use these improved measures. (Scott Winship has made a similar point using more limited data from the U.S., though his estimates would be hard to compare directly to the ones Heckman and Landersø report.)

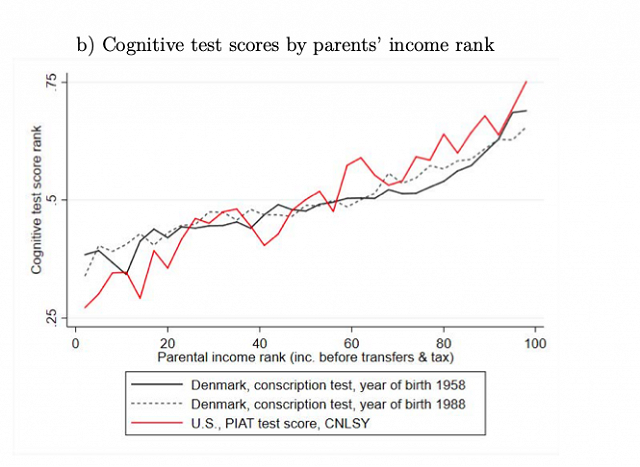

But Heckman and Landersø are able to measure mobility in some other ways too—ways that relate directly to human capital and are easily comparable to estimates from the U.S. In both Denmark and the U.S., for example, parents’ years of schooling are correlated pretty strongly with their kids’ years of schooling—and “for the cohorts born in the mid-1980s, estimated educational mobility in Denmark is similar to that in the U.S.” The relationship between parents’ income and their kids’ cognitive-test scores is also similar between Denmark and the U.S.:

Source: Heckman, J., Landersø, R., "Lessons from Denmark About Inequality and Social Mobility," NBER Working Papers, March 2021.

And despite Denmark's aggressive efforts to equalize opportunity, richer parents still manage to give their kids a leg up. They sort into neighborhoods to live alongside each other, effectively hoarding their social capital. And notwithstanding a rule requiring all teachers to be paid the same, the teachers with the highest scholastic-test scores still end up teaching in the places with the highest-educated parents. “Teachers in affluent neighborhoods,” Heckman and Landersø write, “are arguably paid more through a non-wage mechanism: by having access to quality students.”

Heckman and Landersø call this sort of thing the Matthew Effect, in reference to the biblical verse Matthew 25:29: “to those who have more is given.”

As they note, even somewhere like Denmark, rich parents can give their kids advantages in some major ways:

(i) Through direct parental interactions with children in stimulating child learning, personality, and behaviors. This comes from direct engagement and by setting examples for children to emulate, including supporting, supplementing, and advising schooling and other activities in which children engage. (ii) Through choice of neighborhoods and localities which influence the quality of schooling and the quality of peers. (iii) Through guidance on important lifetime decisions.

I would add (iv): genes, a concept that goes unmentioned in the study. Educational attainment, to take just one relevant trait, is known to be partly genetic, meaning that highly-educated parents will disproportionately have highly-educated kids for that reason alone.

There are several ways the paper’s findings can fit into the current political debate. Limited-government conservatives such as yours truly, for example, will relish the fact that Denmark's huge welfare state doesn’t seem to be having one of its most desired effects.

Certain segments of the Left, though, might not find these results surprising, either. Some, like the socialist Fredrik deBoer, have been trying to incorporate the findings of modern genetics into leftist thought, arguing that “equality of opportunity” isn’t enough when not everyone has the natural ability to succeed equally in a capitalist society. In this way of seeing things, redistribution is an end in itself, and no country should even hope to sever the relationship between parents’ ability to make money in a free market and their kids’ ability. Others on the left might simply respond to this work with a shrug: Denmark doesn’t manage to keep rich parents from giving their kids an advantage . . . but it does channel lots of money toward the poor to help them live easier lives, so what exactly is the problem?

Heckman himself expressed some thoughts about this in a recent interview with AEI. He noted that their findings have not exactly been welcomed warmly in Denmark. And he acknowledged that removing the influence of family is not easy: “Do we want to get to a situation like [Plato envisioned] . . . thinking of putting all children in orphanages to equalize them?” But he also expressed hope we could improve the family environments of the disadvantaged:

I think we do want to harvest the powerful force of love and attachment for the child. That is such a powerful force. And I just think we have to cope with it and then understand that for certain aspects of society, the people who drew a blank in the lottery of life, if you want, or didn’t do so well, that there might be some compensation down the road. And my thinking about what the form of that social insurance might be would be to help supplement the home life and make the home life more effective for the child.

Meanwhile, the paper also takes a swipe at the claims of Raj Chetty and others that neighborhoods, in particular, are enormous drivers of economic mobility, with poor kids from some places being far more upwardly mobile than poor kids elsewhere. Somewhat similarly to U.S.-based research I’ve written about for this blog, Heckman and Landersø note that, in Denmark, the apparent effects of neighborhoods fall when one takes account of various characteristics of the families who live in these places, including their education, criminal involvement, and family structure. If lower-income kids from a certain neighborhood seem particularly likely to move up the ladder, in other words, that might be because they have higher-educated and married (and so on) parents, and not because the neighborhood itself has magical effects. Or, as Heckman put it in a recent interview with this site, “the family is the whole story.”

To be fair, though, not even Chetty has claimed that all variation in mobility across neighborhoods is causal, though in one study he estimated that “at least 50%” of it is. See my previous piece for more detail on how he reached this conclusion by leveraging some “natural experiments” (such as “displacement shocks” that forced families to move to new neighborhoods abruptly) and why some others are skeptical.

Heckman and Landersø's new paper makes a number of important contributions. But the biggest point here might also be the simplest: A big welfare state can give money to the poor, but it can't make life fair.

Robert VerBruggen is an Institute for Family Studies research fellow and a policy writer for National Review Online.