Overview

Working mothers are back in the headlines. Between January and June of 2025, the monthly labor force participation rate among mothers with young children dropped by nearly three percentage points, erasing much of the post-pandemic recovery in female employment. As reported in Time magazine, this downturn appears to be driven by shifting workplace policies like mandatory return-to-office requirements and widespread federal layoffs. Others, including The New York Times, have speculated that the Trump administration’s priorities may be playing a role.

While this fluctuation in women’s employment might prove temporary, it is important to examine the long-term trajectory in the United States. Equally critical is the question of how we can better support parents, especially mothers, in balancing family and work responsibilities, a key concern for working women in America.

In this report, we explore the long-term trends of prime-age women’s employment in the U.S., pinpoint what mothers want when it comes to work and family, and highlight their most important work-family policy priorities. We also examine the current support systems available to mothers, and identify the key areas where we, as a society, can better support families.

Main Findings

First, despite the “stalled revolution” in women’s overall labor force participation over the past two decades, mothers with children under age 5 (traditionally, the group least likely to be in the workforce) have experienced an increase in their employment rates, according to our analysis of the latest Current Population Survey (CPS) data. This shift is driven entirely by a rise in labor force participation among mothers with young children who are married, the group that accounts for 75% of mothers with pre-school age young children in 2025. Among prime-age married mothers with children under age 5 at home, the labor force participation rate rose from 63% in 2000 to 69% in 2025. In contrast, the rate declined for unmarried mothers of similarly aged children (from 75% to 70%).

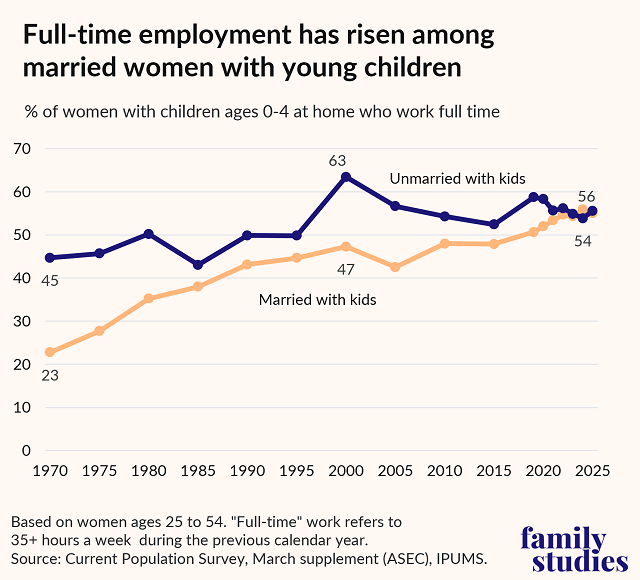

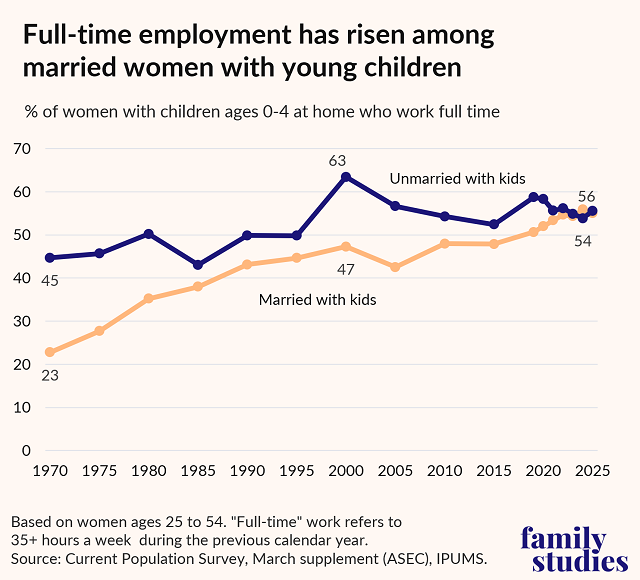

Second, the increased labor force participation of married mothers with young children is largely due to an increase in full-time employment. In 2024, for the first time since data have been recorded, married mothers with young children were more likely than unmarried mothers to be working full-time for pay (56% versus 54%). That share dipped slightly for married mothers in 2025, making both groups about equally likely to work full time today.

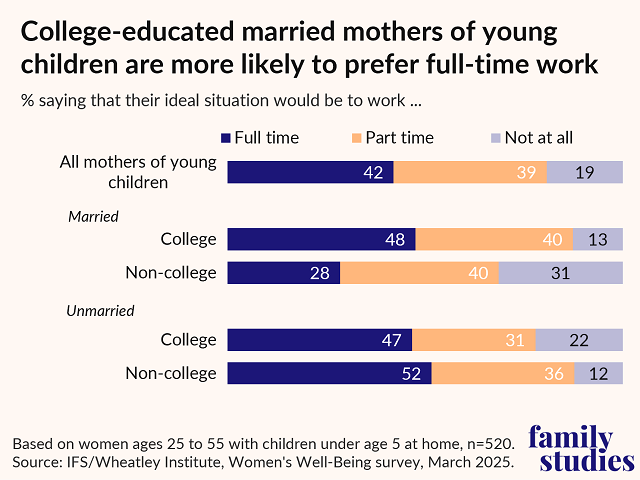

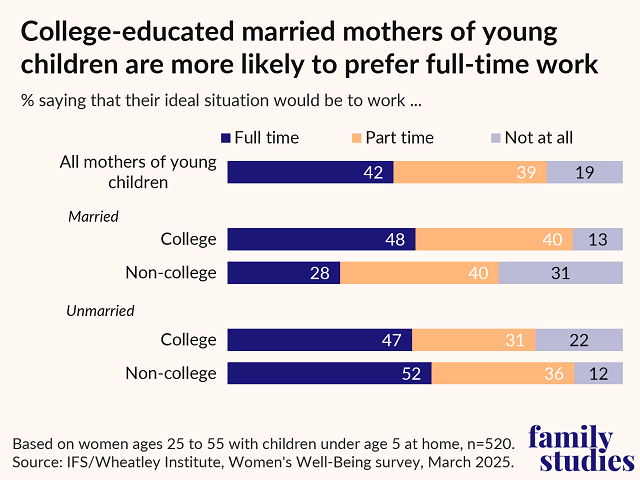

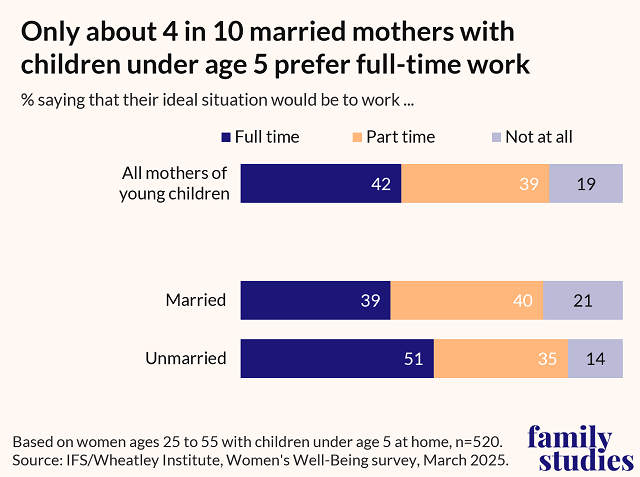

Even with the rise in full-time employment among mothers, full-time work is still not the preferred arrangement for married mothers with preschool-aged children. Only 39% of married mothers with children under age 5 at home say their ideal arrangement is to work full time, roughly equal to the 40% who prefer part-time work. An additional 20% say they prefer not to work for pay at all, according to a recent IFS/Wheatley Institute survey of 3,000 women ages 25 to 55. In fact, full-time employment is not the preferred arrangement of the majority of U.S. mothers. Overall, 47% of all mothers with children under age 18 prefer full-time work, 37% prefer part-time work, and the rest prefer not to work for pay at all.

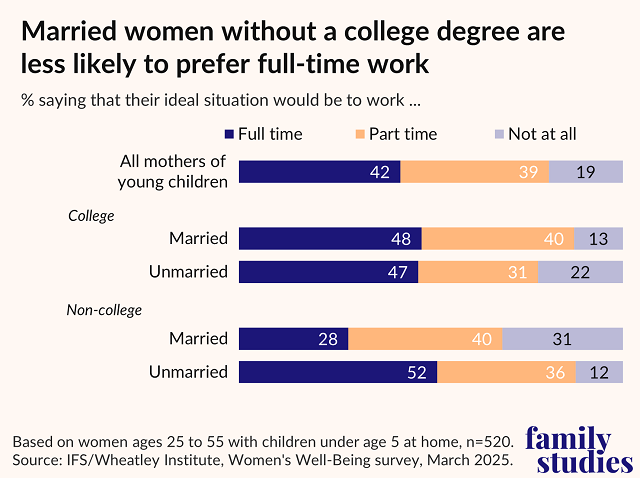

Mothers’ education plays a role in their preference of work arrangement. Among married mothers with children under age 5, college-educated mothers are much more likely than their peers with less education to say their ideal situation would be to work full time (48% vs. 28%), while both groups are equally likely to say they prefer part-time work (40%).

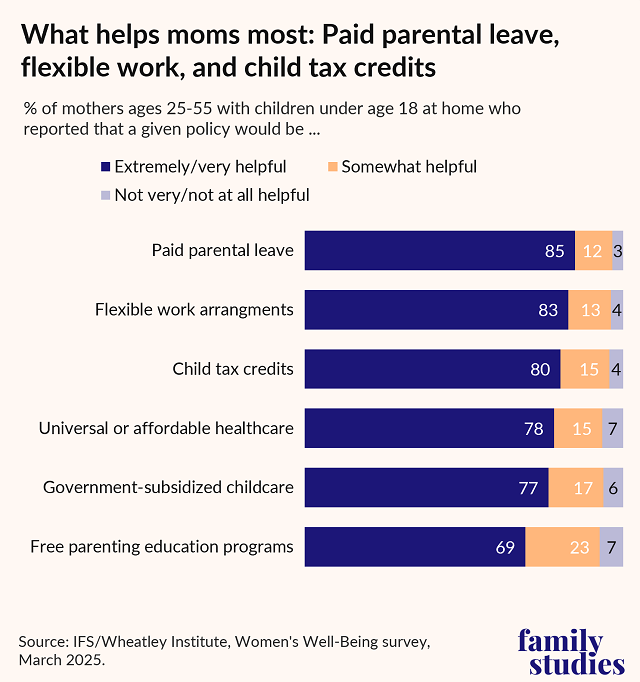

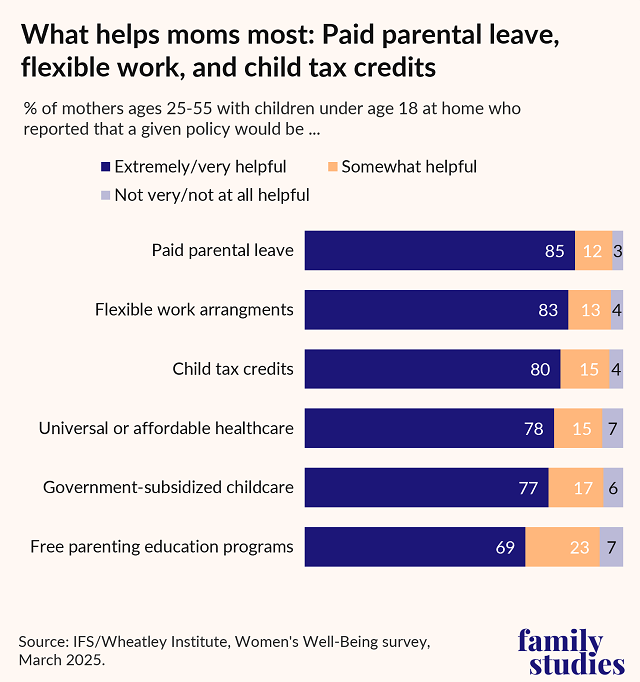

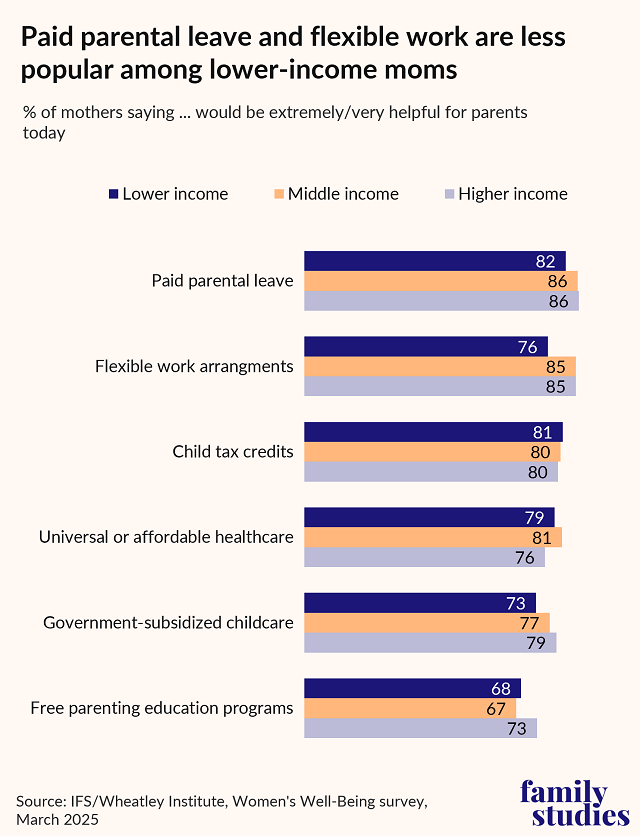

When it comes to the job the government is doing to help families, a majority of mothers (60%) in the same survey say the government is not doing enough. Among the list of government policies offered, mothers with children under age 18 choose paid family leave, flexible work arrangements, and the child tax credit as their top policy priorities. Further analysis by income shows that mothers in the middle- or higher-income brackets are more likely than lower-income moms to say paid parental leave and flexible work are vital for parents today. In contrast, lower-income mothers tend to prioritize the child tax credit over flexible work.

Other Key Findings

- Married mothers tend to have higher levels of education than unmarried mothers, and the gap has grown over time. In 2025, about half of married mothers (52%) have a college or higher education, compared with 25% of unmarried mothers. This divide is even bigger among mothers with pre-school age children: 58% married mothers and 20% of unmarried mothers are college educated.

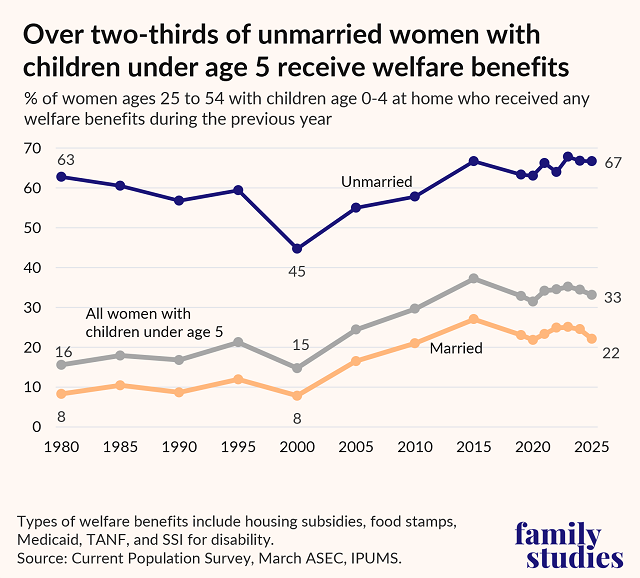

- Welfare benefits may contribute to the decline in full-time employment among unmarried mothers. In 2025, over two-thirds of unmarried women with children under 5 (67%) received some form of welfare assistance, up from 45% in 2000. In this study, welfare benefits include housing subsidies, food stamps, Medicaid, TANF, and SSI for disability, but exclude school lunches and childcare assistance.

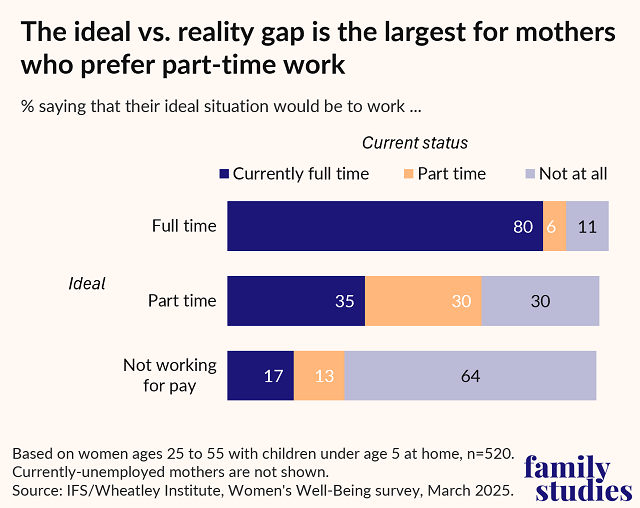

- Part-time work presents the largest gap between preference and reality for mothers of young children.According to the IFS/Wheatley survey, 80% of mothers with children under age 5 who prefer working full time are doing so, and 64% of mothers who prefer not working for pay are currently not working. However, only 30% of mothers who prefer working part time are doing so.

- Government subsidized childcare is viewed as a relatively lower priority by mothers when considering what helps parents most. Higher-income moms are more likely than moms with lower incomes to say “government-subsidized childcare programs to provide high-quality, affordable, and accessible childcare for working parents” are extremely or very helpful (79% vs. 73%), yet this still doesn’t rank among the top three priorities for high-income mothers.

- Mothers’ support networks today primarily consist of a spouse or partner, along with extended family members. About three-quarters of mothers (74%) say their spouse, partner, or the child’s father have provided a lot or some help, and 64% say the same about extended family. Paid childcare plays a more limited role (39%), while neighbors rank lowest among the sources of support for mothers.

About the Data

Findings in this report are based primarily on two sources: data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Current Population Survey (CPS) and the new Women’s Well-Being Survey (WWS) from the Institute for Family Studies and the Wheatley Institute.

Employment Data: Unless otherwise noted, all employment analyses in this report are based on data from the CPS’s Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) for the years 1970, 1975, 1980,1985, 1990, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010,2015, and 2019-2025, obtained from the IPUMS CPS database (https://www.ipums.org) and constructed by the authors.

The CPS is a nationally representative survey of about 60,000 households, conducted jointly by the U.S. Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The CPS covers the civilian noninstitutionalized population of the U.S. and is the primary source of labor force statistics for the U.S. population, while the ASEC provides additional detailed information on income, poverty, household composition, and demographic characteristics.

Employment status measures whether respondents were in the labor force (working or seeking work) during the previous week, which includes those who are currently employed, unemployed, and those in the armed forces. Full-time and part-time work status indicates whether respondents who were employed during the previous year usually worked full time (35 hours a week or more) or part time.

Public Opinion Survey Data: The WWS was conducted by YouGov between March 1 and 12, 2025, with a representative sample of 3,000 women ages 25 to 55 living in the U.S., including 1,551 with children under age 18.

YouGov interviewed 3,035 respondents and matched 3,000 to a sampling frame based on age, race, and education, constructed from ACS microdata, public voter files, the 2020 CPS Voting and Registration Supplement, NEP exit polls, and CES surveys. Matched cases were weighted using propensity scores derived from age, race/ethnicity, education, and region, grouped into deciles and post-stratified. Additional weighting adjustments were made to reflect the most current employment patterns as well as marital and parental status.

The characteristics of the final weighted sample mirror those of the general U.S. population of women ages 25 to 55, with a margin of error of +/- 2.11 percentage points. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) adults are included but are not analyzed separately. All estimates have been weighted to reflect the actual population.

Rising Employment Among Married Mothers With Children

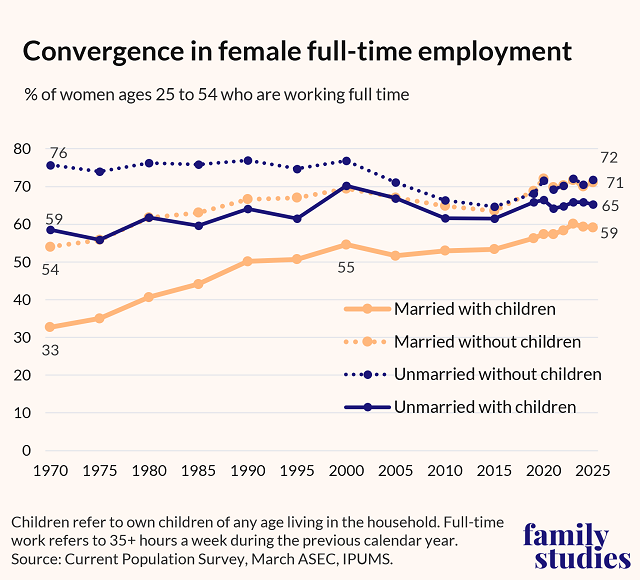

Women’s labor force participation in the U.S. rose sharply between the 1970s and 1990s, but it has largely stalled since the turn of the century. Sociologists refer to the past two decades as a “stalled revolution” for gender equality in the workplace.

However, the overall trend for women’s employment masks some important shifts in the past few decades. Changes in women’s employment trends based on the presence of children in the household—as well as in marital status—suggest that marriage and children play a diminished role in shaping women’s labor force participation today.

Married mothers are also significantly more likely to be very happy than married women without children and unmarried women with children. The analyses presented in this report control for age, family income, and education, so these factors cannot be the reason for the differences.

Figure 1: Percentages of women ages 25 to 54 working full time by presence of household children.

Source: Current Population Survey, March supplement (ASEC), IPUMS.

Specifically, prime-age women with children under age 5, the group with the lowest rate of full-time employment historically, increased their participation in the full-time workforce over the past two decades. Women with school-age children also increased their rate of full-time employment during that same period. The full-time employment rate among women who do not have children at home is very close to its 2000 value, however.

Married mothers with children—traditionally the least likely to be employed full time—are also more likely to work full time today than in 2000, when overall female employment peaked. In contrast, the share of full-time employment has declined among unmarried mothers with children since 2000.

Figure 2: Percentages of women ages 25 to 54, by marital and parental status, who are working full time.

Source: Current Population Survey, March ASEC, IPUMS.

The rise in female employment is especially pronounced among married mothers with young children at home. In fact, the largest increase in labor force participation has occurred among married mothers with children under age 5, from 63% in 2000 to 69% in 2025 (see Appendix for details). Most of this reflects a growing percentage of married mothers of young children working full time, the share of which increased from 47% in 2000 to 55% in 2025.

In contrast, unmarried women with young children under age 5 have seen a decline in their overall labor force participation rate, from 75% to 70% since 2000. The share of single mothers with young children under age 5 who work full time dropped from 63% in 2000 to 56% in 2025.

Figure 3: Percentages of women with children ages 0-4 at home, by marital status, who work full time.

Source: Current Population Survey, March supplement (ASEC), IPUMS.

What Is Driving More Married Mothers of Young Children to the Workplace?

Economic pressures on families have likely played a role in these trends. Over the past decade, economic concerns have rapidly become one of the most important pressures that families face. In 2025, 73% of Americans pointed to economic challenges as the “most important issues facing families today,” up from just 51% in 2015, according to data from the long running American Family Survey (AFS). In contrast, concerns about cultural issues, such as a decline in religious faith and children growing up in single-parent homes, have declined significantly over the same period.

Specifically, “the costs associated with raising a family” rank as the top issue families say they face today, exceeding concerns over crime, sexual permissiveness, parental discipline, religion, and a range of other cultural and structural issues, according to the same survey.

Moreover, with the rise of inflation in recent years, the real wage (adjusted for inflation) for American workers has declined. Even before the Covid era, Americans’ purchasing power had stayed flat over the previous four decades.3

Dual-income families have also been on the rise. In 2024, nearly 50% of all married-couple families have dual incomes, compared with 23% in which one spouse is employed. The 1950s model, where one person’s wage could support the whole family and afford a house, is no longer attainable for most Americans.

One could argue that this perception of financial strain may be shaped by a higher expectation for the standard of living. Americans live in larger homes and own more cars today, and many things once considered luxuries are now the expected norm. The economic gains of the past five decades have enabled higher consumption, which contributed to this elevated expectation. For many families, a dual income now feels necessary to keep up with these growing norms.

As this IFS/Wheatley survey finds, only 39% of married mothers with pre-school age children prefer working full time, while a greater share either prefer part-time work (40%) or not working for pay at all (21%). This suggests that many married mothers with young children who currently work full time may be doing so due to economic pressures, rather than because they view their current arrangement as ideal.

On the other hand, this rising employment trend may also signal a generational shift among today’s mothers with young children, most of whom belong to the Millennial generation (ages 29 to 44). In 2025, the median age is 34 for married mothers with children under age 5 at home, and 30 for unmarried mothers with children of the same age living at home. Compared with previous generations, Millennials, especially women, are significantly more educated. Indeed, women now outnumber men in the college-educated labor force, a shift likely driven by rising educational attainment among younger women.

In fact, married moms today are among the most educated group of women. More than 52% have a college degree or higher, comparable to married, childless women (55%), and unmarried, childless women (49%). In contrast, unmarried mothers tend to have lower educational attainment, with just about 25% holding a college degree. This divide is even more pronounced among mothers of preschool-aged children: 58% married mothers in this group are college educated, compared to just 20% of their unmarried counterparts.

To be clear, the rise in full-time employment among married mothers does not appear to be driven by changes in their spouse’s employment. Married men with children have the highest employment rate of any male group across marital and parental statuses. This pattern has held steady for the past 50 years, with the share of full-time employment among married fathers above 90 percent. As of 2025, 92% of prime-age men with children at home are working full time, compared with 82% of unmarried men with children (see Appendix for details).

Figure 4: Percentages of women ages 25 to 54, by marital and parental status, who have a college or higher education.

Source: Current Population Survey, March ASEC, IPUMS.

Even though full-time work is not what most mothers with young children prefer, college-educated married mothers are much more likely than married mothers without a college degree to describe their ideal work situation as full time (48% vs. 28%), according to the new IFS/Wheatley survey of women.

A college education seems to have an independent effect on mothers’ preferences for full-time work, regardless of their marital status. Married college-educated mothers are about as likely as their unmarried peers to say they prefer full-time work (48% vs. 47%). However, they are also more likely to prefer part-time work (40% vs. 31%), and less likely to prefer not working for pay at all.

In addition to a stronger career orientation, the desire for full-time work among college-educated married mothers may be driven by economics. College-educated women are more likely to work in higher-paying professional jobs, so leaving the workforce to care for children full time carries a much higher opportunity cost than for women without a college degree. Meanwhile, about 26% of Millennials have student debts, a higher share than any other generation. Women also are more likely than men to take on student debt, and this financial pressure may motivate many married mothers to remain in the workforce rather than exit it.

Figure 5: Employment status preferences, by marital status and education, of mothers of young children.

Source: IFS/Wheatley Institute, Women’s Well-Being survey, March 2025.

Therefore, both the economic pressures on working families and a career orientation from higher-educated married mothers with young children may help explain why we see an upward trend among this group of mothers.

On the other hand, the downward trend in full-time employment for unmarried mothers with young children is puzzling. This could reflect the differences in educational attainment and employment opportunities between married and unmarried mothers. Only 20% of unmarried mothers with children under age 5 are college educated, far below the share among married mothers (58%). In fact, the unemployment rate among unmarried mothers with young children was 5%, compared with 1% for married mothers among young children.

Welfare benefits may also play a role. Welfare reform in the mid-90s during the Clinton era cut the welfare caseload significantly but not for long. Among prime-age Americans, the share who receive any welfare benefits rose from 9% in 2000 to 22% in 2015 and currently stands at 21% (see chart in Appendix). Today, more than two-thirds of unmarried mothers with children under age 5 at home receive welfare benefits, compared to 45% in 2000. Married mothers with preschool-aged children have also seen an increase in welfare benefits over the past two decades, although their share remains much lower than that of unmarried mothers.

Figure 6: Percentages of women ages 25 to 54 with children age 0-4 at home, by marital status, who received any welfare benefits during the previous year.

Source: Current Population Survey, March ASEC, IPUMS.

Mothers' Work Preferences: Full Time, Part Time, or Not at All?

Part-time work has been the top preference for American mothers over the past two decades. As late as 2018, part-time work remained the top preference for mothers, over working full time or not working for pay at all. However, recent surveys suggest that full-time employment has gained some traction among mothers.

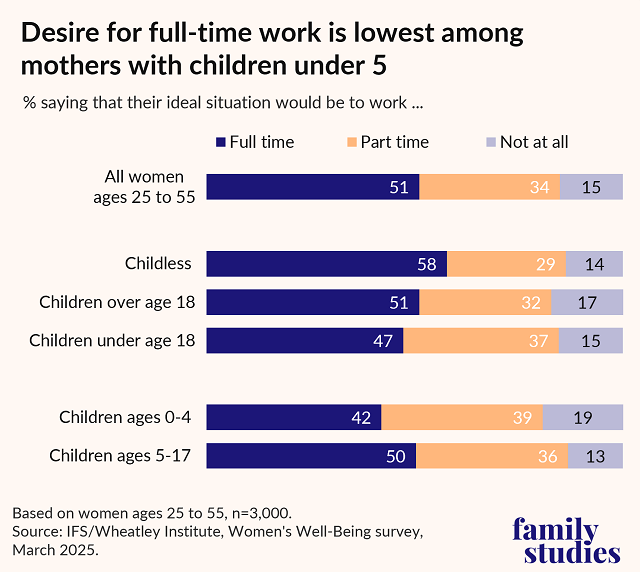

While still a minority, 47% of women with children under age 18 say their ideal situation would be working full time, which is higher than the 37% who prefer part-time work and the 15% who prefer not working for pay, according to the new IFS/Wheatley survey.

The preference for part-time employment among mothers with children under age 18 today has decreased since 2012, when it was 47 percent.3 At the same time, the percentage of mothers with children under age 18 who prefer not to work at all has remained roughly the same as 2012. This indicates that the change in work preference for mothers with children has largely been from part-time employment toward full-time employment.

Looking at women today overall, about half of prime-age women in the U.S. (51%) prefer full-time work, roughly one-third prefer part-time work, and the remaining 15% prefer not working for pay at all. Women’s preferences are dependent on a few factors, including whether they have children at home, their marital status, as well as other socio-economic conditions.

Presence of Children at Home

As in the past, women’s preferences for full-time work today are clearly tied to whether they have children at home, as well as the age of their children. While 58% of prime-age women who are childless prefer full-time work, the share goes down to 47% for those with children under age 18 at home.

Mothers with young children under age 5 today are the group least likely to say their ideal situation is full-time work. About 42% in this group prefer full-time work, compared with 50% of mothers with school-age children at home.

Figure 7: Employment status preferences, by age of children, of women ages 25-55.

Source: IFS/Wheatley Institute, Women’s Well-Being survey, March 2025.

Marriage and Education

Meanwhile, married mothers with children under 5 are less likely to prefer full-time work than their unmarried counterparts (39% vs. 51%), although this is largely dependent on the education level of mothers.

Figure 8: Employment status preferences, by marital status, of women ages 25-55 with children under age 5 at home.

Source: IFS/Wheatley Institute, Women’s Well-Being survey, March 2025.

Among college-educated mothers of young children, about equal shares of married and unmarried mothers prefer full-time work. However, among mothers with young children who do not have a college degree, married mothers have a strong preference for not working full time. Only 28% of married mothers in this group prefer full-time work, compared with 52% of unmarried mothers.

Figure 9: Employment status preferences, by marital status and education, of women ages 25-55 with children under age 5 at home.

Source: IFS/Wheatley Institute, Women’s Well-Being survey, March 2025.

Income and Ideology

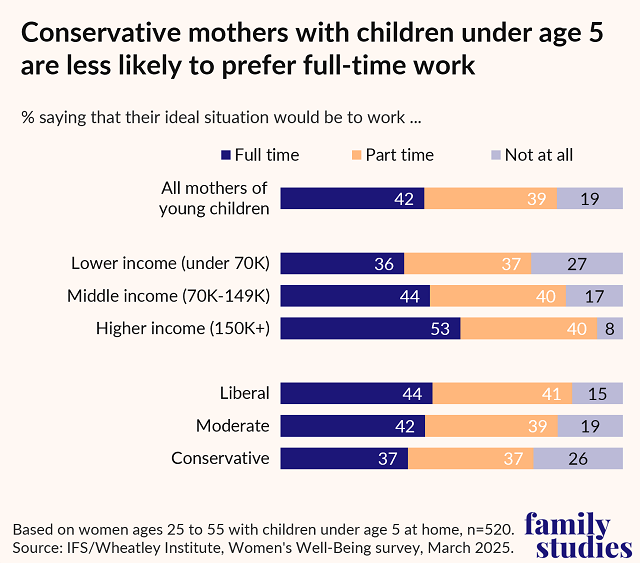

The work preferences of mothers with young children also vary by their family income and ideology. More than half of mothers with annual incomes of at least $150,000 say they prefer working full time, but only 36% of mothers with an annual income at or below $70,000 do. That preference differs sharply from 2012, when 25% of mothers with higher incomes said full-time employment would be ideal, compared to 40% of mothers with lower family incomes.

Among married mothers with children under age 5, the income of their spouse also plays a role in shaping their work preference. Mothers who outearn their spouses are much more likely to say their ideal work would be full time (65%), compared with their peers who earn less than their spouses (29%).

Figure 10: Employment preferences, by family income and ideology, of mothers with children under 5 at home.

Source: IFS/Wheatley Institute, Women’s Well-Being survey, March 2025.

Moms' Ideal Work Arrangement vs. Reality

Part-time work presents the largest gap between preference and reality for mothers of young children. According to the IFS/Wheatley survey, 80% of mothers with children under age 5 who prefer working full time are doing so, while 64% of mothers who prefer not working for pay are currently not working. However, only 30% of mothers who prefer working part time are doing so.

Figure 11: Comparison of current and ideal work statuses among women ages 25 to 55 with children under age 5 at home.

Source: IFS/Wheatley Institute, Women’s Well-Being survey, March 2025.

Most Moms Say Government Support for Parents Falls Short

The U.S. is unique when it comes to family-friendly policies. Among 41 high- and middle-income countries today, it is the only country where paid leave for new parents is not legally mandated. While such policies are often viewed as obvious and important for supporting mothers and families, research suggests that they can also introduce long-term challenges, such as burdening families with higher tax rates and unintentionally suppressing senior-level positions for women.

When asked whether the government does too much, too little, or about the right amount to address issues affecting parents today, a majority of women with children under age 18 (60%) say government is doing too little to help, 11% say too much, and 29% say about the right amount, according to the IFS/Wheatley survey. Mothers across education levels and income brackets share similar views.

Our analyses indicate that a one-size-fits all policy approach will not effectively address the needs of mothers. Mothers ranked paid parental leave (85%), flexible work arrangements (83%), and child tax credits (80%) as their top three policy priorities to better support families. Yet, further analysis by income shows that mothers in the middle- or higher-income brackets are more likely than lower-income moms to say paid parental leave and flexible work are vital for parents today. On the other hand, child tax credits are favored over flexible work among lower-income moms.

Figure 12: Percentages of mothers ages 25-55 with children under age 18 at home who reported that a given policy would be helpful.

Source: IFS/Wheatley Institute, Women’s Well-Being survey, March 2025.

Flexible work arrangements are especially appealing to college-educated mothers. Some 86% say that flexible work arrangements (including remote work and part-time options) are either extremely or very helpful to parents, compared with 81% of mothers without a college degree. In fact, a flexible work schedule is seen as the top policy priority for college-educated mothers, slightly ahead of paid family leave at 85% (see Appendix for more details). These preferences likely reflect the higher opportunity costs they face when stepping back from work, suggesting that mothers’ policy priorities can be shaped by work opportunities and constraints.

Compared with paid parental leave and flexible work arrangements, government-subsidized childcare is viewed as a relatively lower priority by mothers when considering what helps parents most. College-educated mothers are more likely than their less-educated counterparts to say that “government-subsidized childcare programs to provide high-quality, affordable, and accessible childcare for working parents” are extremely or very helpful (79% vs. 75%), yet they still favor flexible work arrangements over childcare support. Similarly, higher-income mothers are more likely than those with lower incomes to rate such programs as extremely or very helpful (79% vs. 73%), but this option still does not rank among the top three priorities for higher-income mothers.

Figure 13: Percentage of mothers, by family income level, who predict that a particular policy would be helpful.

Source: IFS/Wheatley Institute, Women’s Well-Being survey, March 2025.

These findings are consistent with survey data gathered in the months after the pandemic subsided. More than half of parents said that they preferred working from home at least half of the time, flexibility that emerged as a result of the pandemic. Work flexibility plays an important role in facilitating the type of childcare arrangement mothers say they prefer. In the same post-Covid survey, 37% of mothers with young children identified “both parents work flexible hours and shared childcare” as the best arrangement for families with pre-school age children. In contrast, only 8% viewed center-based childcare as the best arrangement.

In fact, flexible work arrangements are common among female workers these days. In the IFS/Wheatley survey, about 50% of women with children under age 18 who work full time or part time report that they have at least one day a week that they work remotely, and a slightly lower share (47%) of women who do not have children under age 18 at home say they work remotely at least one day a week.

College-educated mothers are much more likely to have jobs with flexibility. Among mothers who are working full or part time, 58% of college-educated mothers with children under age 18 say they work at least one day remotely, compared to 41% for mothers without a college education, according to the same survey.

It Takes a Village to Raise a Child, But Families Do the Lion's Share

Raising children involves some of the most rewarding, yet exhausting work. Time diary research shows that parents find caring for their children to be much more exhausting than their paid work. That’s why having a strong support network is essential, not just for parents, but also for children’s development.

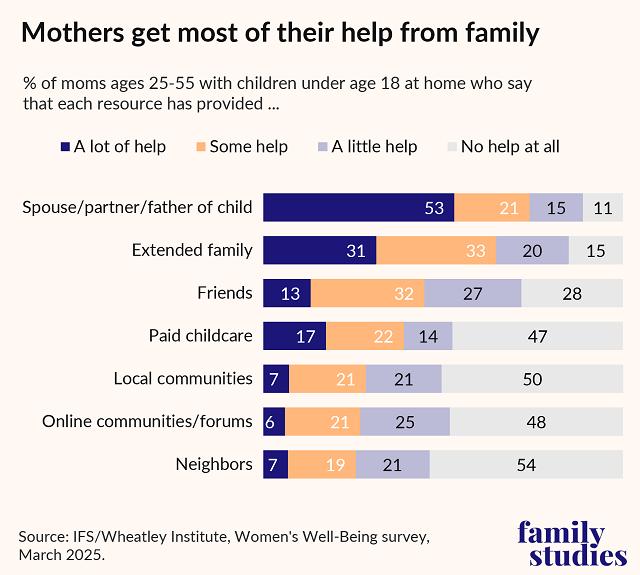

However, the support network parents experience on a day-to-day basis today appears to be much smaller than in previous generations. For most mothers with children under age 18 at home, their spouse or the father of their children is the main source of help: about half of mothers (53%) say they have received a lot of help from their spouse or father of their children, and 21% say they have received some help. Marital status also matters. Married mothers are about twice as likely to report receiving a lot of help from their spouses compared to unmarried mothers (63% vs. 31%).

Extended families rank as the second most common source of support for mothers raising children. One in three mothers (31%) say their extended family, which includes grandparents or siblings, have provided a lot of help, and one-third say they received some help, but an equal share of mothers (35%) say they received little or no support at all from their extended families. Married and unmarried mothers are equally likely to receive help from extended families, but since unmarried mothers get less help from their partner or father of their child, extended families often become a primary source of support.

Mothers also get help from paid childcare as well as friends, but the two sources are much less important than extended family. Only 17% of mothers suggest paid childcare played an important role in helping them raise children, and 13% said the same about their friends. Overall, fewer than half of mothers in the survey report receiving either a lot or some help from these sources.

Neighbors, once a vital part of the “village” that helped raise children, now rank at the bottom among key sources of support for mothers. They are even less helpful to mothers than online communities or forums. Just a quarter of mothers (26%) report receiving at least some help from neighbors, while more than half of mothers (54%) say they have received no help at all. Similarly, local communities, including churches, play a limited role in supporting mothers. Half of mothers say they’ve received no help at all from their local communities, while only 28% report receiving at least some help.

Figure 14: Amount of help mothers have reported receiving from various resources.

Source: IFS/Wheatley Institute, Women’s Well-Being survey, March 2025.

A separate analysis of mothers with children under age 5 at home suggests a similar pattern. These mothers also rely heavily on their spouse/partner (80%) or extended families (71%) for help. They receive comparable levels of support from paid childcare (42%) and friends (44%), though more report receiving a lot of help from paid childcare (22%) than from friends (12%). Once again, local communities and neighbors play a limited role in supporting mothers of young children—similar to the level of support from online communities.

No Single Policy Solution

Being married and having children appear to be less important in shaping the employment patterns of women today. Recent decades have seen an increase in full-time employment of married mothers with children under age 5, the group that was previously least likely to be employed. During the same period, unmarried mothers of young children have experienced a drop in employment rates. Some of the increase in married mothers’ employment is the result of economic pressure, especially post-Covid inflation, and an increased cost of living. Nearly three-quarters of Americans report being worried about the cost of living, and over half feel that their expenses are rising faster than their incomes. Economic anxiety is undoubtedly shaping mothers’ employment preferences and desires.

This change in employment patterns among married mothers of young children also reflects a demographic shift. Today’s married mothers of young children are predominantly Millennial women, who are highly educated and surpass men by a widening margin in the attainment of bachelor’s degrees. As of 2025, 58% of married mothers of young children are college educated, compared with 20% of their unmarried counterparts.

Married mothers of young children with a college degree are much more likely to identify full-time employment as their ideal (48%), compared with their counterparts without a college degree (28%), and far less likely to prefer no employment at all (13% vs. 31%). A college degree appears to significantly shape women’s orientation toward full-time employment across their life course, including during the years when they have young children. For these women, not working may be “more expensive” than working, even if it means paying for childcare.

Many of these mothers need greater support as they navigate the complexities of work and family life. For college-educated mothers, flexibility in where and when they work is a key support, enabling them to respond to family needs while meeting the demands of work. A substantial body of research confirms the powerful role of flexibility in reducing conflict between work and family life.

In contrast, lower-income mothers and mothers without a college degree view direct financial support, such as child tax credits, as more helpful for families, enabling one parent to stay at home to care for children, while the other is employed. Given the work options available to them, these women may not feel the same pull to participate in the work force, as job flexibility may not be possible.

When it comes to what helps parents the most, government-subsidized childcare is viewed as a relatively lower priority by mothers. Higher-income and college-educated mothers are more likely than others to favor childcare assistance, yet even among these moms, it ranks behind paid family leave and flexible work arrangements. This pattern reflects mothers’ strong desire to provide care for their own children while they are young—and to find solutions for balancing work and family life.

The distinctions we found here between different groups of mothers confirm that no single policy solution fits all. The best policies are those that strengthen mothers’ capacity to do what they feel is best for their families—whether that involves increased work flexibility and paid family leave, or direct financial assistance to enable a mother to work less. Mothers are empowered when they have more options to choose from.

The persistent decline in the fertility rate highlights the critical need for family-friendly policies today. Mothers and families need support. Children are our future. Empowering and supporting women in their role as mothers is not only vital to their well-being, but also one of most important and meaningful ways to invest in the next generation.

Note: Download the full report for the Appendix

End Notes

1. For year-to-year comparisons, we focused on usual hours worked per week during the previous calendar year. Additional analyses were conducted among full-time, year-around workers as well as those working full time in the previous week; similar trends were observed across multiple measures.

2. During the same period, the share of married mothers who work part time declined from 22% to 16%

3. Alternative inflation measures suggest that real wage for American workers have modestly increased since the 1970s. See: Scott Winship, “Introducing the more accurate consumer price index,” AEI Center on Opportunity and Social Mobility, November 2024.