Highlights

“[H]ypergamy turns out to be a stubborn thing,” Kay Hymowitz wrote in a 2020 IFS blog post, adding, “It seems that the highly-credentialed alpha female still prefers a mate above her pay grade.”

But has hypergamy—defined in this article as marrying someone with a higher income—remained the norm for young American women since then? Or have shifting social and economic trends narrowed, or even eliminated, average differences in income between brides and grooms?

To explore these questions, I evaluated recent American Community Survey (ACS) data for newly-married and never-married adults ages 18-39.1 Because second marriages, caring for children, and school enrollment could influence personal incomes, I focused on adults who were not in school, had no household children, and had not been previously married.

The results show that women do still tend to marry men who earn more money than they do. In addition, the differences in median incomes between recently-married women and their spouses are far greater than those among never-married men and women. This indicates that hypergamy, as defined in this article, remains an active phenomenon among young-adult women.2

Men Still Tend to Outearn Their Wives

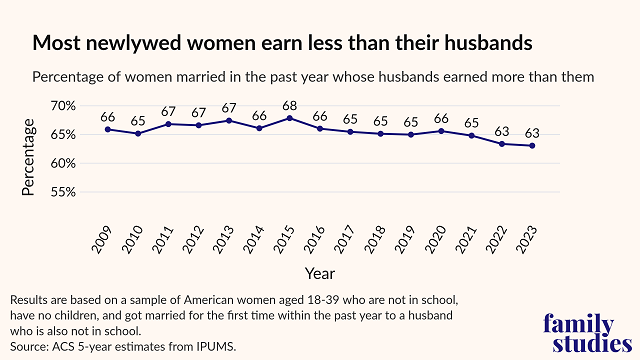

In 2023, 63% of recently married young-adult women were outearned by their husbands, 32% earned more than their husbands, and 5% had the same income.3 The percentage of women who married higher-earning husbands has changed little since 2009, when it was at 66 percent.

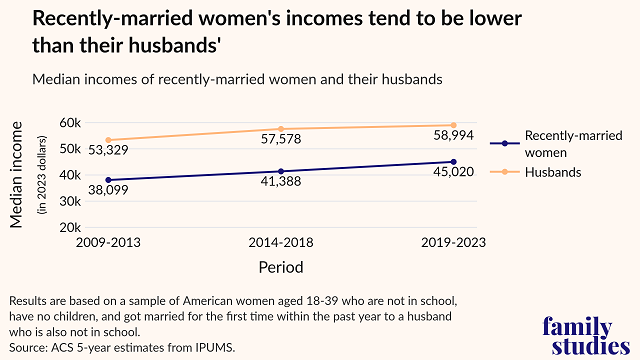

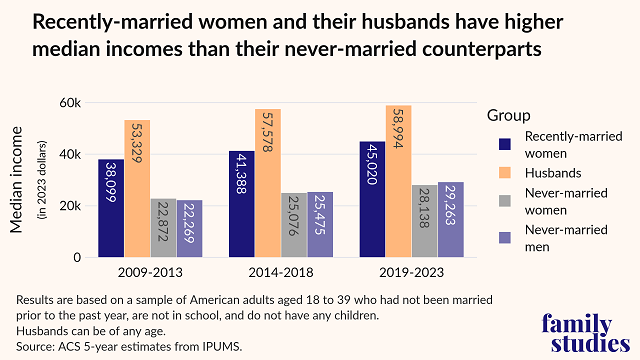

The median income of recently married women (in 2023 dollars) did grow from $38,099 during 2009-2013 to $45,020 during 2019-2023, a sign of women’s rising economic fortunes. However, their husbands' median incomes also increased from $53,329 to $58,994 during that same timeframe, thus maintaining an income gap between these groups.

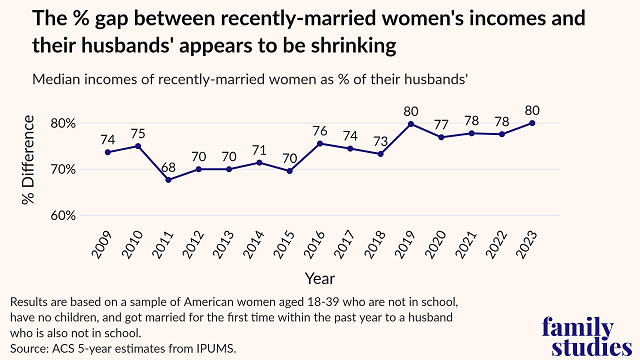

However, in percentage terms, this income gap may be shrinking. In 2011, the median personal income of recently married women was only 68% of their husband’s income; that percentage increased to 80% by 2023. Although Pilar Gonalons-Pons and Christine Schwartz concluded in a 2017 article that "newlywed couples’ earnings are not more similar today than they were in the past," the latest ACS data suggests that the nuptial gap in earnings has recently begun to narrow.4

In Most Income Brackets, Women Marry Men Who Earn More

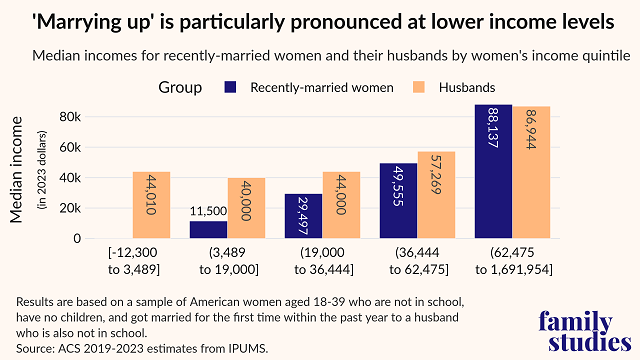

Although young-adult women who recently got married tend to earn less than their husbands, this discrepancy in median income varies considerably by income level.5 As the following chart shows, recently married women in the lowest income quintile (i.e. the lowest-earning women) had a median income of $0; meanwhile, their husbands earned an average of around $44,000. Similarly, women in the next-lowest quintile were outearned by their husbands by over $28,000. However, this gap decreased to around $8,000 within the second-highest quintile—then disappeared at the highest quintile.

Interestingly, median spousal incomes for recently married women were higher at the lowest income quintile than at the next-lowest quintile. One possible explanation is that some of the women in this income category were able to stop working after getting married; this would have then shifted them into the lowest income category.

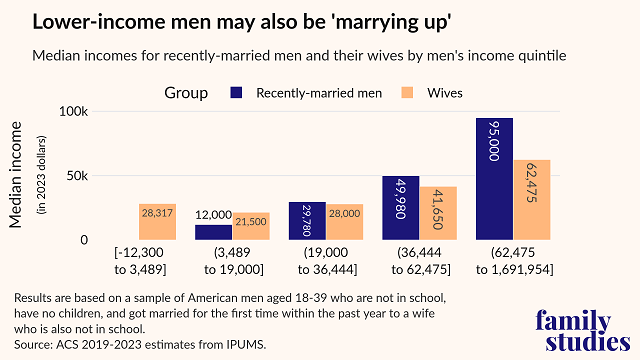

Recently married men in the lowest two income categories also have lower median incomes than their wives, suggesting that they, too, may be 'marrying up.' Even so within each quintile, the median incomes of these men's wives are much lower than are those of recently-married women's husbands. This suggests that hypergamy is more prevalent among women than men.

From 2019 to 2023, the majority of women in each of the four lowest income quintiles married higher-earning men. However, a sizable percentage of women in the highest quintile (43%) also married men whose incomes exceeded their own.

Never-married Income Data Can't Explain the Spousal Income Gap

The ACS shows that young-adult women normally marry men who earn more. Some might argue that this is because men simply tend to earn more than women in general. However, among never-married young adults who aren't in school and don't have any kids at home, the median incomes between the sexes are very similar—and thus can't explain the major income differences observed among newlyweds.

During 2019-2023, never-married women had a median income of $28,138, similar to the $29,263 median income for never-married men. As the following chart shows, this gap is much smaller than the gap between recently-married women and their husbands, who had median incomes of $45,020 and $58,994, respectively.6 (It's also notable that, during all three periods, recently-married women had much higher median incomes than did their never-married female counterparts.)

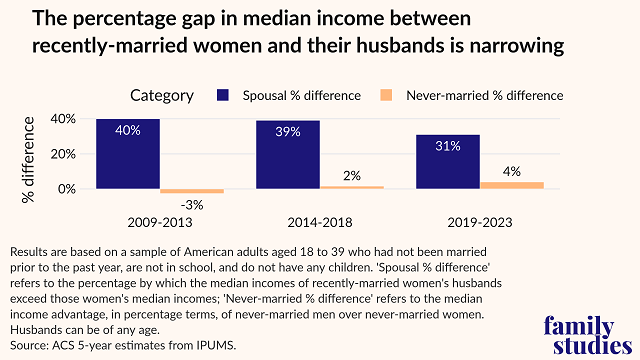

However, this spousal income gap has been narrowing in recent years. While recently-married women's husbands earned 40% more than they did during 2009-2013, this gap decreased to 31% during 2019-2023. Meanwhile, the percentage difference in median income between never-married men and women has remained quite steady.7

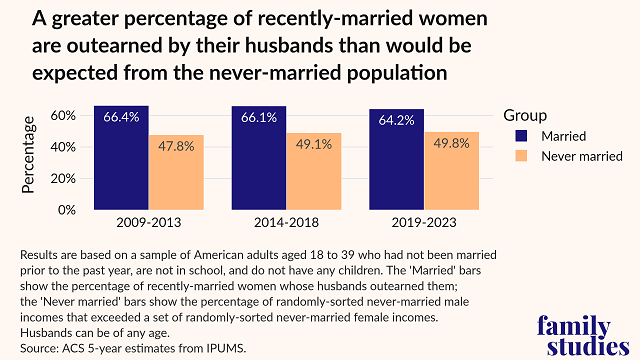

To further compare income differences between recently-married couples and their never-married counterparts, I sorted never-married men's and women's incomes randomly, then determined the percentage of randomly-sorted pairs that had higher male incomes. Next, I compared these percentages to the percentage of recently-married women who were outearned by their husbands.

As the following chart shows, the percentage of women who married higher-earning men is higher than we might expect from our random pairings of never-married male and female incomes. During each period, around two-thirds of recently-married women were outearned by their husbands; meanwhile, only around half of never-married male incomes within each randomly-assigned pair were higher than their corresponding female incomes. This is not because women who chose to marry earned less than those who haven't yet gotten married; in fact, as discussed earlier, the opposite is true.

Conclusion

In a recent Forbes piece, Mark Travers argues that "the traditional hypergamous model, where women sought partners with superior economic or social status, is becoming outdated." However, recent ACS data shows that it's still the norm for young-adult women to marry men who outearn them. Furthermore, the similar median incomes among never-married men and women indicate that that the income differences between newlyweds aren't simply due to higher earnings among men in general. This suggests that hypergamy, rather than becoming outdated, remains a powerful factor in modern-day relationship decisions.

It's true that these findings do not prove that women prefer to marry higher-earning men; it's always possible that another trait, such as education or ambition, leads to both higher incomes and higher marriage rates. However, a 2017 Pew surveyindicates that men's earning potential is still important to the opposite sex: 71% of women said that in order for a man to be considered a good spouse or partner, it is "very important" that he have the capacity to provide financially.

Given that women appear to prefer to marry higher-earning men, the growth in the percentage of working-age men who are outside the labor force could, in turn, help explain the shrinking percentage of men who are married. As Brad Wilcox notes in Get Married, "this disconnect between men and full-time work . . . has reduced the appeal and accessibility of marriage for all too many men in America." Wilcox and IFS Research Director Wendy Wang further explained in “The Marriage Divide” that these employment challenges have hit working-class men particularly hard, thus widening the gap in marriage rates between higher- and lower-income Americans.

Ultimately, these findings indicate that in order to reverse declines in the marriage rate, it will be important for men with and without college degrees to have access to solid, well-paying jobs that will help them appeal to a potential spouse. A new IFS/PRRUCS report by Brad Wilcox and Grant Martsolf provides a detailed explanation of the relationship between job characteristics and marriage rates.

Ken Burchfiel is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies.

1. Citation for the IPUMS dataset from which this data was retrieved: Steven Ruggles, Sarah Flood, Matthew Sobek, Daniel Backman, Grace Cooper, Julia A. Rivera Drew, Stephanie Richards, Renae Rogers, Jonathan Schroeder, and Kari C.W. Williams. IPUMS USA: Version 16.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2025.

To help control for the effects of children, school attendance, previous marriages, and marriage itself on income, I limited my sample to individuals who (1) did not have children living with them; (2) were not in school; and (3) had either gotten married for the first time within the past year or had never married. In order to focus my analyses on heterosexual marriages, I also filtered my income comparison dataset to exclude same-sex couples. In addition, when comparing respondents' income with that of their spouses, I also filtered out rows in which the spouse was enrolled in a school and/or had been married more than once. In addition, I filtered out rows for which spousal income data were not available. (Many of these rows reflected spouses who were not living with the respondent or marriages that were no longer active.) The ACS dataset reports personal incomes for the past 12 months rather than at the time individuals got married. Thus, the incomes within this dataset may differ significantly from those that respondents had on the date they were married.

2. It is important to clarify that marrying a higher-earning groom does not necessarily mean that a woman is entering a higher social class. As noted earlier, this article defines hypergamy in terms of income, not class. A separate analysis would be needed to determine how likely it is for women to marry men of the same social class; a recent article by Clark and Cummins indicates that, at least in England, marrying within one's class is the norm.

3. Although this article limits its analyses of recently-married women to those ages 18-39, their husbands could be of any age and may thus differ in important respects (including income) than the men in the 18-39 age group whom this article also profiles.

4. The chart indicates that this narrowing began in 2019 and thus likely cannot be explained only by COVID—which did not become widespread in the US until 2020.

5. These income levels were calculated by dividing incomes for all adults aged 18-39 with valid data into quintiles. Separate quintiles were calculated for the three periods presented in this article. All incomes are expressed in 2023 dollars.

6. As mentioned earlier, the men whom these women married could have been older than 39. This could help explain why their median incomes are higher than those of the never-married men. However, it's possible that one reason women prefer to marry older men is the fact that they have higher incomes.

7. When I included respondents with children in my comparisons, I found higher gaps in income between never-married men and women than those presented here. However, this adjustment also increased the gaps in income between recently-married women and their husbands.