Highlights

- While all men experienced significant declines in marriage and family formation, working-class men were hit especially hard over the last few decades. Post This

- "Good job" characteristics explain nearly 80% of the difference in marriage rates between working-class and college-educated men, per our new report. Post This

- The findings strongly suggest that the nature and quality of work are closely tied to class-based differences in marriage patterns in the United States. Post This

The last 50 years have been difficult for many working-class Americans. Beginning in the late 1970s, the U.S. economy entered a period of rapid deindustrialization, leading to a significant decline in manufacturing jobs—jobs that had long provided reliable, well-paying employment for Americans without a college degree (a common definition of the “working class”), especially men. Economic prospects for this group have suffered considerably. Between 1979 and 2019, real wages for workers without a college degree declined by 11%, while wages for the median college graduate increased by 15 percent.

The challenges facing working-class Americans extend beyond economics. They have also seen a broad erosion of key social institutions traditionally associated with a flourishing life. One institution arguably hit hardest is the family.

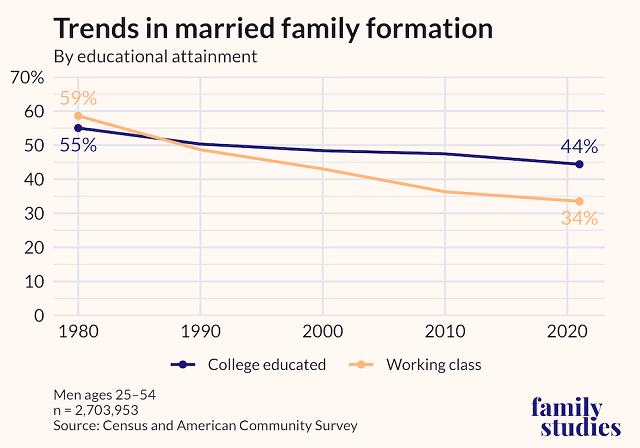

In a new IFS/PRRUCS report, Brad Wilcox and I show that, in 1980, working-class men ages 25–54 were actually four percentage points more likely than college-educated men to be married with children at home. However, that changed rapidly over the following decades. While all men experienced significant declines in marriage and family formation, working-class men were hit especially hard. By 2021, only 34% of working-class men were married with children at home, compared to 44% of college-educated men.

There are certainly many factors driving these trends, but the worsening economic prospects of working-class men are clearly among the most important. We know that marriage and work are closely linked. For example, women are more likely to be attracted to potential partners that can reasonably provide for a family—men with well-paying, stable jobs that offer benefits. Likewise, men with families are more likely to work and to pursue stable, higher-quality employment.

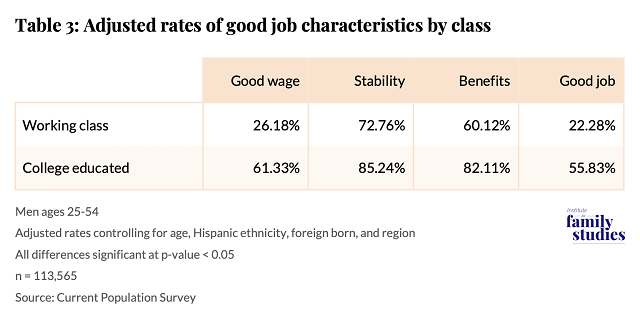

In our report, we confirm that college-educated men of prime working age tend to hold significantly better jobs than their working-class counterparts, based on key “good job” characteristics: strong salaries, benefits, and job stability. When we examine all three of these factors together, we find that only 23% of working-class men ages 25–54 meet the threshold of earning more than $60,000 per year, having health insurance, and holding a full-time job without being laid off—compared to 56% of college-educated men.

We also find that these job characteristics explain nearly 80% of the difference in marriage rates between working-class and college-educated men. It’s important to note, however, that our analyses were cross-sectional, meaning we cannot definitively conclude that good job characteristics caused the differences in marriage rates. For instance, men who possess certain virtues that make them good employees—such as honesty and dependability—may also be more likely to be good spouses and fathers. Similarly, men who marry and have children may become more motivated to seek and maintain stable, well-paying jobs. While we cannot speak directly to causality, the findings strongly suggest that the nature and quality of work are closely tied to class-based differences in marriage patterns in the United States.

Any approach aimed at strengthening marriage must consider the nature of jobs for working-class Americans in a rapidly changing economy.

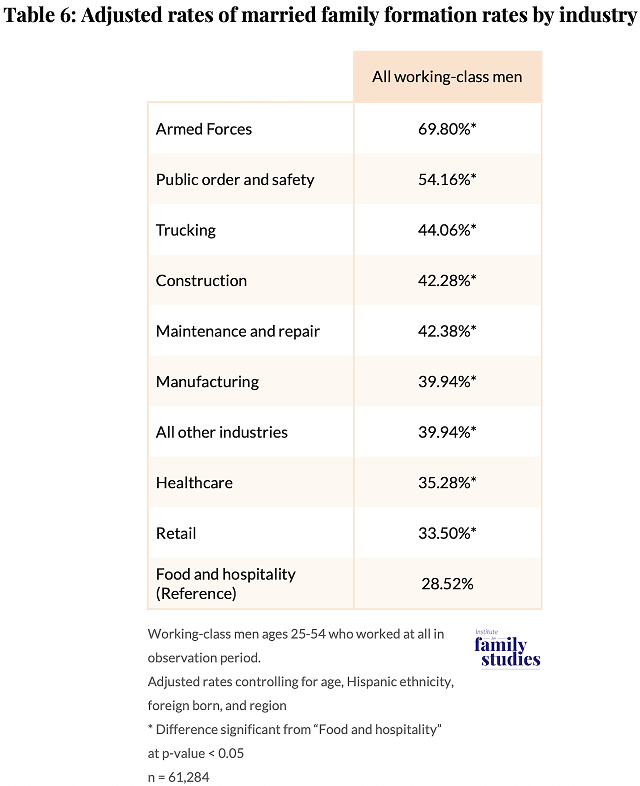

That said, many working-class Americans continue to marry and form families. This raises an important question: Are certain types of working-class jobs more conducive to marriage and family life? In this same report, we examine variation in marriage and family formation rates across industries that commonly employ working-class men. We find substantial differences across these industries in terms of “good job” characteristics. For example, only 12% of prime-age working-class men in food and hospitality hold jobs that meet all three criteria—earning over $60,000 annually, having health insurance, and working full-time without experiencing a layoff—compared to 54% of those employed in public order and safety. This reflects a striking disparity in job quality across sectors.

Likewise, we also find significant variation in terms of marriage and family formation among prime working age working-class men, which closely mirror the quality of jobs within those industries. The lowest marriage and family formation rates again are found in food and hospitality at 29%. The highest rates are among armed forces (69%), public order and safety (44%), and trucking (44%). However, the good job characteristics explain some but not all of these differences in marriage and family formation rates across industries.

This suggests that certain industries, such as trucking, may support marriage and family formation in ways not entirely explained by job characteristics alone. For example, based on recent interviews with truckers that I conducted for another project, a significant number come from communities—such as farming communities—where marriage is culturally prioritized. Likewise, these men shared that the social support provided by marriage likely offers a stable home base that helps them to endure the demands of long-haul travel.

All in all, the findings in our new report highlight the deep interconnection between class, work, and family formation. Any approach aimed at strengthening marriage must consider the nature of jobs for working-class Americans in a rapidly changing economy.

Download the full report, Good Jobs, Strong Families: How the Character of Men's Work Is Linked to Their Family Status, published jointly by the Institute for Family Studies and Penn's Program for Research on Religion and Urban Civil Society.