Highlights

- If lawmakers want to expand public funding of child care or other safety-net expansions, they should argue for it on its merits, not as a response to the pandemic’s impact on the labor market. Post This

- If anything, the share of college-educated mothers of young children have been more likely to return to pre-pandemic levels relative to other groups Post This

- Moms with young kids and men without a college education and no kids present were already less likely to be in the labor force than comparable groups. Post This

As the Senate continues to negotiate what might be included in the multi-trillion dollar “Build Back Better” reconciliation package, part of the rationale for such an expansive package has been the pandemic’s damage to female participation in the labor market. “Biden’s plan will reverse the she-cession,” ran one CNN headline, using the cloying portmanteau coined to refer to the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on women’s labor force participation. Ting Ting Cheng and Marcy Sims of Columbia Law School’s ERA Project wrote that Biden administration’s proposals would be a New Deal-like “investment in the U.S. economy that [would] foreground gender equity and the needs of women.”

But the narrative of an ongoing shock to female employment needs some correcting. To the extent there was a negative impact, it seems to have predominantly limited to those first initial months when life was turned upside down. If lawmakers want to expand public funding of child care or other safety-net expansions, they should argue for it on its merits, not as a response to the pandemic’s impact on the labor market.

What made the pandemic-induced recession different, of course, was that it hit in-person jobs much harder than other recessions. When the economy slows down, manufacturing or construction firms, which disproportionately employ males, will usually cut back, while female-dominated service-sector jobs like health care and education continue with their usual business.

But during the first months of COVID-19, those services were closed or reduced, leading to the first recession that disproportionately impacted industries that tend to hire women. Schools and child care shut down and only slowly re-opened, making it more difficult for working parents to balance family and work demands. Add to that the fact December 2019 was the first time in American history that women held a majority of nonfarm payroll jobs, and economists and politicians alike were quick to worry about the potential impact on the national economy and women’s labor market status.

But the impact seems to have been less widespread than had been feared. Over the summer, Jason Furman and Melissa Kearney found evidence that “the widespread challenges that parents across the country have faced…are not a driver of continuing low employment levels.” They pointed out that women with young children comprise only a small portion of the labor force, and that while women with young children did see their employment go down, so, too, did women without children at home.

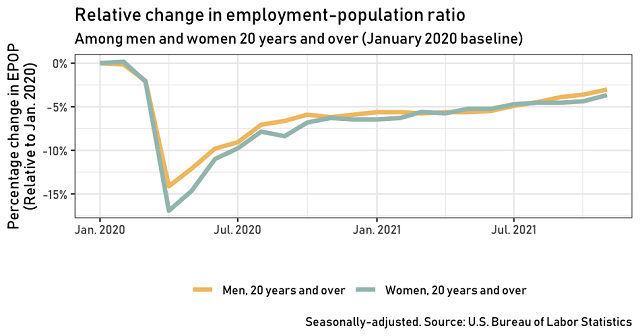

Economists like to measure the strength of the labor market with the employment-population ratio (or EPOP), which is just a measure of how many people in a given population are employed.

For reference, labor force participation among men ages 20 and older stood about twelve percentage points higher than women in January 2020, but both would soon plunge off a cliff. Looking at the relative change since then, women undisputedly bore the initial brunt of the pandemic, but by the end of 2020 had largely closed the relative gap. In the last couple months, the economic recovery has disproportionately helped bring men back into the labor force, but both men and women continue roughly similar trajectories back to where they had been pre-COVID.

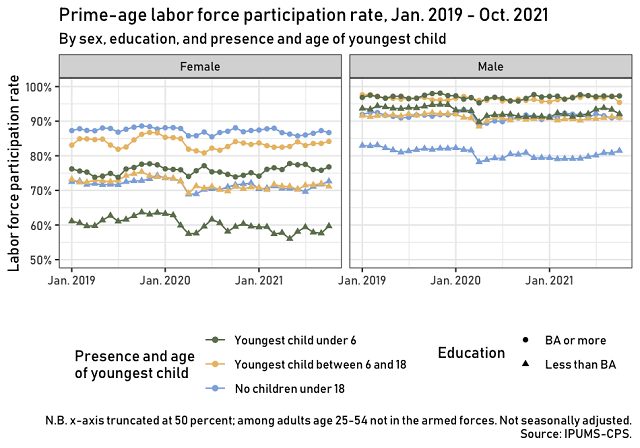

Of course, we might expect to see a greater impact for parents compared to non-parents, or for moms compared to dads. The Current Population Survey gives a micro-level look at how households’ employment changes from month to month, and break these groups down into educational attainment, which shows us some of the intuition behind the Furman-Kearney paper. Moms with young kids and men without a college education and no kids present were already less likely to be in the labor force than comparable groups.

Remember, labor force participation (LFP) is a measure of those working or looking for work, not just those employed. Using this metric, the biggest post-COVID impact is seen in moms without a bachelor’s degree. In October 2021, for instance, the LFP for non-college women with young children stood 4 percentage points lower than it was in October 2019. But, notably, women without a college degree and no children at home also saw their LFP tick down from where it was prior to the pandemic, though less sharply (non-college men without children present also have yet to recover their pre-pandemic rates of working or looking for work.)

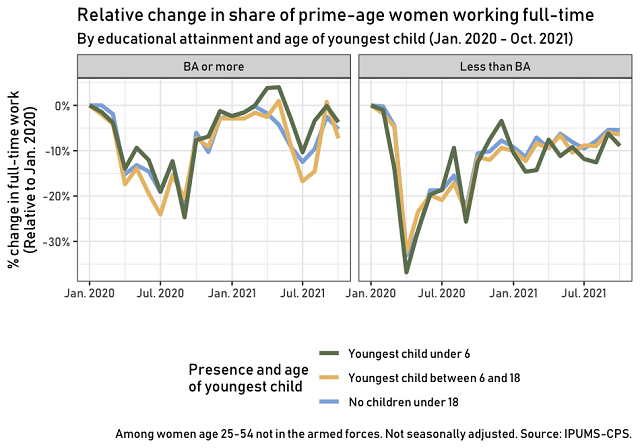

At this point in our economic recovery, the current unemployment rate (those looking for work but unable to find any) is back down to only one percentage point higher than it was just prior to the pandemic. But mothers impacted by the pandemic might be cutting back hours, so we can also check to see if parents are disproportionately represented in those no longer working full-time.

If anything, the share of college-educated mothers of young children have been more likely to return to pre-pandemic levels relative to other groups (these figures are not seasonally adjusted, allowing the impact of summer on female full-time employment to be more visible.) In women without a college degree, we again see a relatively slower return across all three groups—mothers of young kids, school-age children, and women with no children at home at all. Moms of young kids do seem to lag slightly behind the others in the fraction working full-time, but the difference is relatively slight.

What the economic data cannot tell us, of course, is what is going through moms’ minds as they are making the trade-off between a job and family life. Some parents say the pandemic has caused them to reassess their wants and desires from a job. The University of Michigan’s Betsey Stevenson wrote on this phenomenon in a recent report:

Women have returned to work, but not on the same terms. Some are seeking a permanent increase in flexibility, while others want to reduce their work to better achieve work-life balance. And yet others are looking for better opportunities to build the career that they truly want, to be paid a wage that they believe better reflects their contributions. And they are not alone: men, too, are making career changes and want to find a better balance between their family life and their work life.

The biggest drop in labor force participation is seen among non-college educated moms of young kids, who might be more likely to have been working low-wage jobs and thus more open to rebalancing between work and home.

Policymakers can help more families achieve their preferences by pursuing appropriately tight labor markets that boost wages and give workers more power. They can pursue public policies that boost families’ resources and expand their choices by pursuing child benefits, broader choice in education, better paid leave policies, and helping the child care market function more smoothly. But those who wish to expand the social safety net should pursue doing so on its own terms, not as a result of jumping to conclusions about a crisis in female employment that may end up, largely thanks to a much faster economic recovery than in 2008, being less worrisome than it first seemed.

Patrick T. Brown (@PTBwrites) is a fellow with the Ethics and Public Policy Center.