Highlights

- An impressive new paper from Princeton’s Henrik Kleven implies that the EITC has done essentially nothing to increase work. Post This

- The EITC made sure that working families had more money regardless of the incentives it created (or didn’t). Post This

- Why did none of the EITC boosts affect the gap between single mothers and women with no kids, when the credit has always been strongly targeted at the former? Post This

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is a major part of America's work-focused safety net. At the end of each tax year, parents who work but have low incomes can receive up to $6,557 (as of 2019). Conservatives like it because it rewards work; liberals like it because it helps poor families. Some on both sides have suggested expanding it, especially for childless workers, who receive far smaller credits than those with children (just $529 this year).

An impressive new paper from Princeton’s Henrik Kleven, however, argues that the pro-work impact of the EITC has been hugely overstated. Indeed, it implies that the credit has done essentially nothing to increase work. This doesn't mean we should repeal it. But it does mean we should give serious thought to reworking how it operates.

Researchers have long thought that the expansion of the EITC in 1993 played an important role in the dramatic increase in single mothers' labor-force participation in the years that followed. However, it's always been difficult to separate the impact of the EITC from that of welfare reform and the overall strong economy. The paper argues compellingly that these latter two factors are the ones that really mattered.

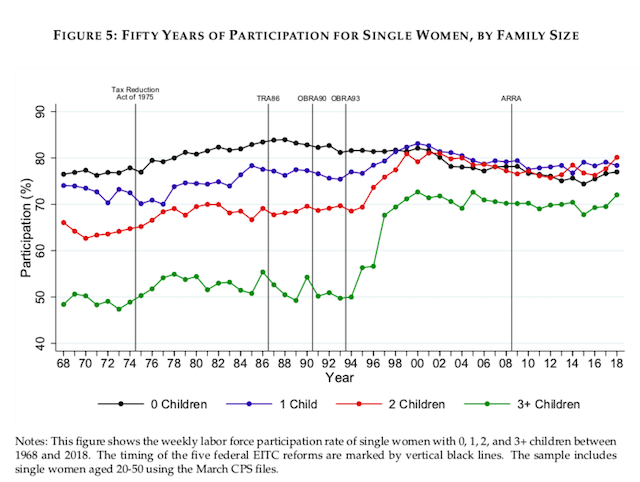

The study is extensive and complicated, featuring a variety of arcane statistical exercises laid out in fancy regression notation. But many of its main points are captured in this simple chart, depicting the labor-force participation of single women with varying numbers of children.

Source: Henrik Kleven, "The EITC and the Extensive Margin: A Reappraisal," Sept. 2019.

Let's walk through some details that won't be apparent unless you know a lot about how welfare policy changed during this time period.

For one thing, it's clear that something very unusual happened in the mid-1990s. In just a few years, single mothers as a group closed the gap they'd previously had with single women without kids. By the turn of the century, single moms with one kid were working more than childless single women. Before and after this period, all these women experienced broadly similar trends: increasing participation in the ’70s and ’80s, declining participation in the current century.

That in itself raises uncomfortable questions for the EITC because 1993 wasn't the only time it expanded. There was also a big boost in 1975, when the credit was first established and was made available only to those with kids, followed by smaller hikes in 1986, 1990, and 2009. Why did none of these boosts affect the gap between single mothers and women with no kids, when the credit has always been strongly targeted at the former?

The other troubling fact is that single mothers seemed to have a stronger response the more kids they had. Those with three or more kids increased their participation by about 20 percentage points; they’re not pictured on the chart, but women with four or more kids had an increase of almost 30 points. Meanwhile, those with one child saw growth of 10 percentage points; those with two, 15.

Now, women with fewer kids had less growth potential because they already worked more—for instance, it would have been impossible for single moms with one kid to have a 30-point boost because that would have put them above 100% labor-force participation. But the pattern is still striking and clear.

This is damning to the EITC because the increases in labor-force participation do not match the growth of the credit. In 1993, Kleven notes, the credit

increased sharply for all families with two or more children and only modestly for families with one child (relative to those without children). This would predict a sharp divergence in the effects between those with one and two children and little divergence elsewhere.

In other words, the EITC can’t explain why women with three or four kids had a far stronger response than those with two. The observed pattern makes more sense as an effect of welfare reform, which imposed work requirements and time limits on much bigger welfare payments to women with more kids.

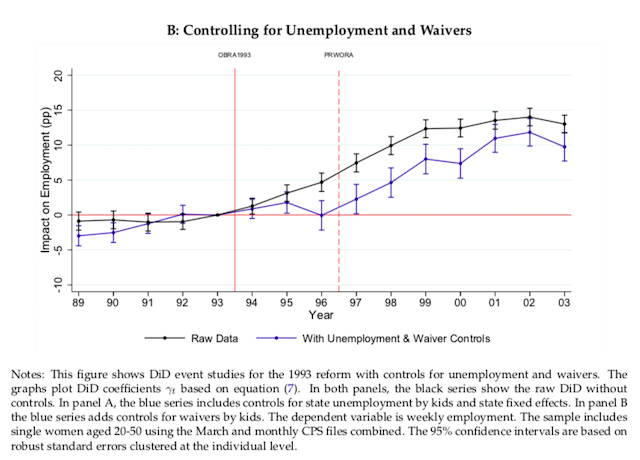

One might reply that we started to see some increases in labor-force participation even before 1996 when the federal welfare-reform law was passed. Indeed, the improvement seems to start right when the EITC was expanded. However, in the years leading up to federal welfare reform, many states implemented similar policies through waivers. And in another analysis, Kleven statistically controls for the presence of these waivers, as well as local unemployment rates, finding that the early increase disappears. This suggests that the pre-1996 improvement was concentrated in the states with waivers, not spread throughout the entire country as one would expect if it resulted from the nationwide EITC expansion.

Source: Henrik Kleven, "The EITC and the Extensive Margin: A Reappraisal," Sept. 2019.

Further, just as some states had welfare reform before it was implemented on the federal level, some states have boosted the EITC on their own. In yet another analysis, Kleven analyzes the impact of state changes to the credit and finds that they had basically no effect on how much single women with kids worked.

How could giving people more money to work fail to increase the chance of them working? There are several possibilities. For one thing, many people eligible for the credit either don’t even know what it is or don't fully understand how it functions, meaning they can't change their behavior to maximize it. And two, it's given out just once a year at tax time, so it doesn't immediately reinforce the behavior it's trying to encourage.

As Kleven notes, he is challenging a fairly strong consensus among other researchers here. Perhaps someone will be able to show that he is wrong. But his results make a strong case—so if he's right, what does that mean for policy?

One can defend the credit even if it doesn't increase work. The EITC made sure that working families had more money regardless of the incentives it created (or didn’t), helping to ensure that those pushed away from welfare and into jobs in the 1990s had an easier time making ends meet.

But this paper should encourage us to think about more effective ways of spending this money. Even if we spent the exact same amount supporting the exact same families, we could do so in a way that makes it clearer why the recipients are getting the funds. There has long been talk of turning the EITC into a wage subsidy that appears in each paycheck rather than an annual windfall, and this new evidence buttresses the case for this approach. It would help poor families to budget and be more likely to incentivize work.

The paper also, it must be said, strengthens the case for work requirements. Foes of welfare reform have often sought to credit the EITC for the gains of the mid-1990s, and it seems they are probably wrong to do so. Going forward, cash welfare's work requirements should be maintained, and similar policies should arguably be strengthened in other programs such as food stamps and housing.

Our welfare system has not seen serious reform in a generation, and those seeking to fix it today are pulling in many different directions. With this entry into the debate, Kleven has made a compelling case that some policies work and others do not.

Robert VerBruggen is an Institute for Family Studies research fellow and a deputy managing editor of National Review.