Highlights

- “The post-2007 decline in births is driven more by a decline in initial childbearing (first births) than by women not having larger families (third and higher order births),” per new paper. Post This

- Diagnosing the decline in fertility, and addressing it, will require more than attributing it to a rising cost of living, the purported pressures of late-stage capitalism, or other economic factors. Post This

- Patrick T. Brown has our 10th most popular blog post of 2022 with a piece on declining birth rates. Post This

Editor's Note: As we near the end of another year, we are counting down our top 10 blog posts of 2022. First up, at number 10, is this article from Patrick T. Brown. It originally appeared on the blog on February 23, 2022.

The Institute for Family Studies blog archives contain 149 posts with the tag “fertility,” stretching back to 2013, so frequent readers need no reminder that America is facing historically low birthrates. But whenever the subject is raised in the press, many commentators show they should have been reading more IFS content.

Many attribute declining birth rates as being primarily due to economic factors, such as sky-high child care costs or increasing student loan debt. But a newly-released paper in the Journal of Economic Perspectives by Melissa Kearney, Phillip Levine, and Luke Pardue is a useful debunking of some of these narratives.

Kearney and Levine have been closely tracking U.S. birthrates, and their paper is a very useful summary of contemporary trends. Instead of economic factors driving lower fertility, the authors posit, “perhaps the key explanation for the post-2007 sustained decline in US birth rates is not about some changing policy or cost factor, but rather shifting priorities across cohorts of young adults.” In other words, it’s not the economy, stupid, but the culture.

It is well known that 2020 saw record-low fertility, as pandemics will tend to dampen birth rates. But the troubling thing is that a booming economy in the second half of the 2010s did nothing to avert the trend. Even before COVID-19 reached U.S. shores, the birth rate among women between 15-44 was 84% of its recent peak in 2007. As IFS research fellow Lyman Stone has estimated, that is the equivalent of 5.8 million “missing” babies.

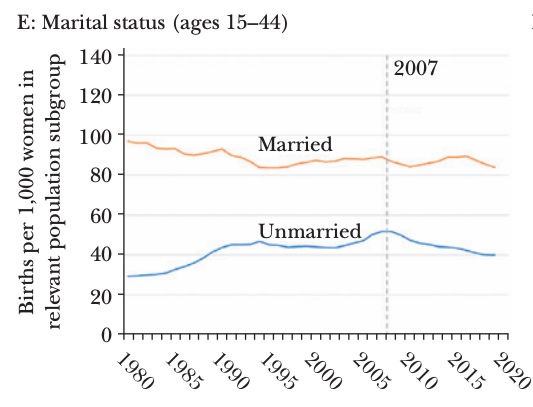

One of the factors to underscore is that the post-2007 decline in fertility is largely a function of declining marriage rates. Birth rates among married women have more or less held steady since the mid-1990s, but declining motherhood among teens and young adults, in conjunction with a delay in the age at first marriage, has pushed unmarried parenthood down to rates last seen in the late 1980s.

Source: Kearney, Levine, Pardue, "The Puzzle of Falling U.S. Birth Rates Since the Great Recession,"

Journal of Economic Perspectives (2022).

It doesn’t seem to be the case that women who might have had multiple children are stopping at one, but rather delayed marriage and childbirth are preventing more women from having any children at all. “The post-2007 decline in births is driven more by a decline in initial childbearing (first births) than by women not having larger families (third and higher order births),” the authors note.

Another major shift is the dramatic decline in Hispanic fertility. As Stone and others have noted, Hispanic women’s childbirth patterns have been “becoming more like other Americans.” Up until 2007, Hispanic women had notably higher birth rates than white and black, but over the past decade, they have converged to around the same levels.

By decomposing the drop in births by mother’s race, age, and education, the authors estimate the biggest share of the decline to be attributable to declining teen pregnancy, but other demographic subgroups contribute as well. White women between the ages of 25 and 29 with college degrees, for example, accounted for 11.9% of the overall decline in fertility.

The lack of a fertility rebound after the Great Recession leads the authors to estimate the impact of a number of hypothetical policy or economic shifts that could be driving lower fertility. Despite changes in economic conditions, as well as policy changes to Medicaid coverage, abortion access, comprehensive sex education laws, and other shifts, they find very little impact on birth rates.

And while their paper isn’t an exhaustive treatment of other presumed barriers to parenthood, they do suggest the conventional wisdom is lacking. States with higher rises in child care costs, for example, did not see a drop in fertility rates. At the same time, they find no evidence that states where religiosity declined the most saw birth rates drop any faster than other states.

Their correlational analysis match-up with a broader body of work. In a research paper published for the Joint Economic Committee, for example, I assessed the state of the evidence around student loan debt and family formation, and found that increased student loan burdens are only marginally related to lower marriage rates for women, and do not appear to be significantly linked to fertility.

The Kearney, Levine, and Pardue paper is also exceptionally useful in summarizing the theory behind fertility decline. Importantly, just because the out-of-pocket costs of parenting aren’t directly lowering birth rates, the opportunity cost of parenting—income, education, experiences, or career opportunities—forgone by having a child seem to be rising in an era of increasing affluence.

This insight cannot be underscored heavily enough. American incomes are at record highs, and standards of living are better than they were in decades past. Assuming would-be parents are opting out of having kids exclusively because of financial pressures misunderstands the dynamic at play.

The authors note that while women under 30 tend to see fertility falling the sharpest, “the decline is generally widespread across demographic subgroups, which gives reason to suspect that the dominant explanation for the aggregate decline is likely to be multifaceted or society-wide.” Building off the work of the late Sara McLanahan, Tomas Sobotka, and Suzanne Bianchi, they speculate that young adults in the U.S. are now much closer to what was already observed in Europe—preferences around childbearing, career, and opportunity costs have indelibly changed compared to prior generations. It’s worth noting that a 2018 poll of individuals who have chosen not have children found the most frequently-cited reason for their decision was a desire for more leisure time.

A cultural shift away from parenthood is something public policy is ill-equipped to address, though that should not take away from discussions about how to make parents’ and children’s lives easier through various tax provisions and spending (a new report from AEI and Brookings suggests some ideas for increasing the share of the federal budget devoted to children.)

But diagnosing the decline in fertility, and addressing it, will require more than attributing it to a rising cost of living, the purported pressures of late-stage capitalism, or other economic factors. Kearney, Levine, and Pardue’s new paper is invaluable in summarizing and explaining why would-be pro-natalists should focus on reducing the opportunity cost of parenthood. This will require a different way of thinking about family policy than assuming a few extra thousand dollars in a child tax credit will be enough to reverse slumping birth rates.

Patrick T. Brown (@PTBwrites) is a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center and a former senior Republican staffer on Capitol Hill.