Highlights

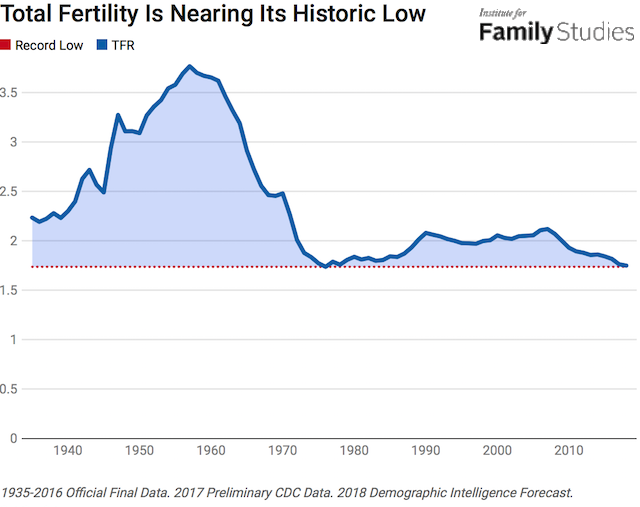

The United States just hit a 40-year low in its fertility rate, according to numbers just released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The 2017 provisional estimate of fertility for the entire U.S. indicates about 3.85 million births in 2017 and a total fertility rate of about 1.76 births per women. These are low numbers: births were as high as 4.31 million in 2007, and the total fertility rate was 2.08 kids back then. The United States has experienced a remarkable slump in fertility over the last several years, as I’ve explained elsewhere.

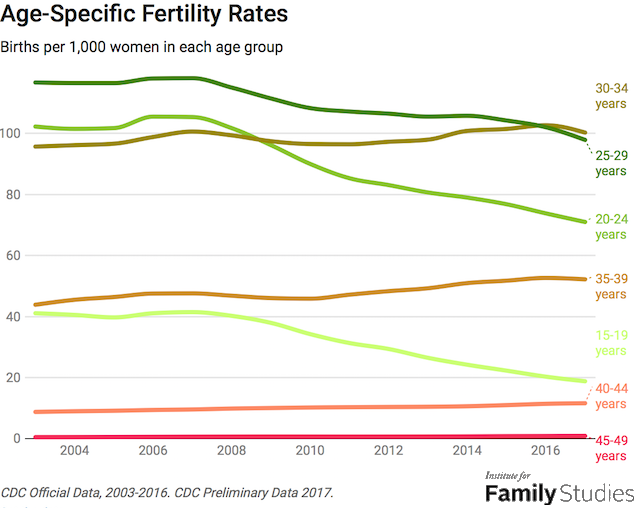

Since 2007, fertility has fallen the most for the youngest women, but in the last year, declines have set in for women in their 30s as well. Fertility declines increasingly seem to be about much more than just postponed fertility, or else these women must be planning to have some very fertile 40s.

At least through 2016, this trend appeared to be mostly driven by changes in marital status. Births to never-married women are down more than births to ever-married women: age-adjusted marital fertility is down 14% since 2007, while age-adjusted never-married fertility is down 21%, as of 2016. Preliminary data from several states suggest these trends are likely to continue in 2017.

When it comes to discussions about declining fertility, conservatives tend to “get it” right away: not having a next generation, or having a far smaller one, will cause problems down the line. In my experience, progressives tend to be more hesitant: is this a back-door argument to keep women out of the workplace? No; in fact, there’s robust empirical evidence most women want more kids. Is this some science-denying attempt to ignore climate change? Again, no; in fact, no plausible trajectory of U.S. fertility has any appreciable impact on carbon emissions. And, one question I find the most perplexing, is this some underhanded racist argument that white people need to pick up the pace of baby-making to out-compete minorities?

It’s true that some people in the right wing have flirted dangerously close to, and sometimes engaged in, the kind of racialized thinking that has tarred pro-fertility initiatives throughout the 20th century, complaining about “other peoples’ babies,” or quietly suggesting that if African Americans have fewer kids, maybe that’s a good thing.

At the end of the day, though, racists on the right are wrong (and comparatively few in number), but so are the progressives who assume that calls for more babies are racially driven.

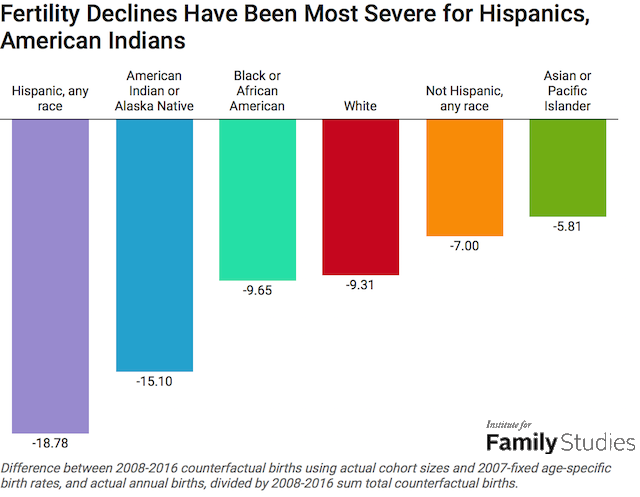

That’s because the decline in fertility has been far greater among minorities than among non-Hispanic whites. If we take age-specific birth rates from the peak-fertility year of 2007 and apply them to each age cohort in 2008-2016, the most recent complete data, we can create a counterfactual scenario of how many babies would have been born if age-adjusted fertility rates had not fallen after 2007. From 2008 to 2016, the deficit turns out to be between 4.1 and 4.6 million missing babies: basically, an entire year’s worth or more of childbearing vanished.

The deficit varies across racial and ethnic groups. American Indians and Alaska Natives have it worst among racial groups, having lost a whopping 15% of expected fertility from 2008 to 2016, or about 83,000 births, with total fertility rates falling from 1.62 births per woman to a shockingly low 1.23. It’s unclear exactly why Native American fertility has fallen so quickly and why it is so low, but they are indisputably the hardest-hit race in the fertility declines of the last 10 years.

Then come African Americans, who are missing 9.6% of expected births, or about 700,000 births, which is only slightly more severe than whites, who are missing 9.3%, or about 3.2 million births. Black fertility declined from 2.15 births per woman to 1.89, while white fertility fell from 2.14 to 1.82. Asians experienced a less severe decline, but their fertility was somewhat lower to start with.

In racial or ethnic terms, America’s “Baby Bust” is kinda, sorta, a little bit racist: it’s hammered Native Americans and Hispanics particularly hard, and hit even African Americans harder than whites generally, and certainly harder than non-Hispanic whites.

But the “white” fertility figure is a bit misleading, as it includes most Hispanics, who have historically had much higher birth rates than non-Hispanic whites. Looking at all Hispanics together, these women are missing nearly 19% of the babies that would have been born from 2008-2016, or about 2.2 million births, as their age-adjusted fertility rates have fallen from 2.85 births per woman to just 2.1, and continue to decline. Meanwhile, non-Hispanic fertility has only declined from 1.95 births per woman to 1.72, yielding about 2.3 million missing births. Solidly half of the missing kids over the last decade would have been born to Hispanic mothers, despite the fact that Hispanics only make up about a quarter of fertility-age women.

Thus, in racial or ethnic terms, America’s “Baby Bust” is kinda, sorta, a little bit racist: it’s hammered Native Americans and Hispanics particularly hard, and hit even African Americans harder than whites generally, and certainly harder than non-Hispanic whites. The call to boost fertility is far from being a call for whites to keep up with minority fertility; rather, it’s an exhortation that we need to be listening to the fertility desires of women of racial and ethnic minorities, who are experiencing precipitous declines in fertility, largely unnoticed by the white-dominated world of mommy-blogs and late-in-life fertility treatments. Any serious pro-natal policy in America worth its salt would primarily result in birth gains among minority mothers, not white ones. Accelerating the national birth rate would also accelerate the pace at which the non-Hispanic white population share declines.

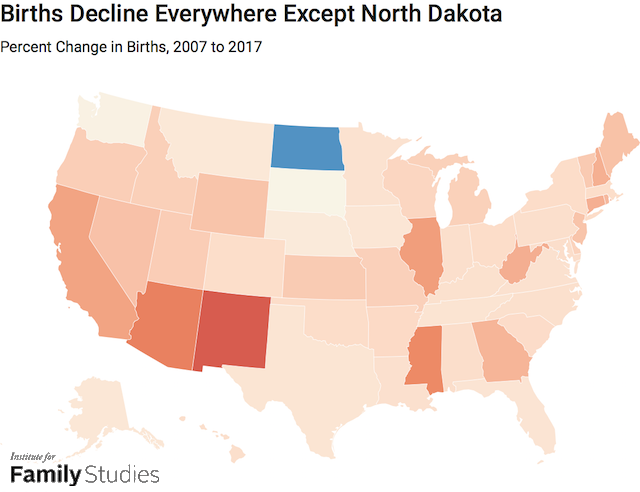

The effect is electorally significant, as well. These lost births are not distributed evenly around the country, as the figure below shows.

Some states have lost far more births than others, while lucky North Dakota has seen an increase in births. But even as declining fertility makes the country’s population whiter, it is making the country’s politics redder: on average, states won by Clinton in 2016 are missing 9% of their expected births since 2008, whereas states Trump won are missing just 7.8%. Within states, Hispanic-, Native American-, and African American-dominated places are seeing the steepest population growth underperformance as a result of missing births. During the 2020 Census apportionment and redistricting process, this will all combine to weaken the political power of minority-heavy areas. The map of declines in 2017 suggests that the observed decline in minority fertility through 2016 almost certainly continued in 2017.

In terms of change in age-adjusted fertility, the sharpest declines in births have been in Arizona, where fertility has fallen from 2.47 births per woman in 2007, to an estimated 1.81 in 2017. Provisional data from early 2018 suggests these declines are likely to continue. Arizona is double-whammied by two different racial or ethnic trends: steep declines among Hispanics and steep declines among Native Americans. Both groups make up a larger share of Arizona’s population than the national average. Both groups have seen steep declines within Arizona; steeper even than their peers in other states.

Other factors are at work, too. Fertility has fallen somewhat more for less educated than for more educated women. Age-adjusted fertility has fallen 15% for women with a bachelor’s degree or less, versus just 7% for women with graduate degrees. On the whole, births to women with no bachelor’s have totaled 12% below what would be expected if 2007 fertility rates had continued, yielding 3.1 million missing births, while births to women with a bachelor’s degree are down 10% for 1.1 million missing births, and births to women with a graduate degree are down just 7%, or 300,000.

In relative terms, these differences are smaller than differences by age or race, suggesting that socioeconomic class is not the biggest driver of changing fertility rates. This is borne out using other variables: Having insurance or not doesn’t seem to make any difference in fertility changes since 2007, and household income also has no clear, linear trend. With more covariates, these factors might have a stronger effect, but they aren’t the dominant story of declining fertility. There are plenty of other factors that could be looked at, but the basic conclusion is pretty straightforward.

Race, ethnicity, marital status, and geography are the best predictors of changes in fertility over the last decade. Fertility declines are most strongly associated with factors that are race- or region-specific, not broadly class-specific, as different economic classes appear to have quite similar trends. This doesn’t rule out all economic causes: there are important interactions between race and socioeconomic class. But this association does suggest two key takeaways to be kept in mind when discussing declining fertility: it is disproportionately landing on minority moms, births have fallen most for unmarried women, and economically-oriented solutions may only have modest direct effects.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, and an International Economist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, where he forecasts cotton market conditions. He blogs about migration, population dynamics, and regional economics at In a State of Migration.