Highlights

- When marriage is no longer strongly dictated by the wider culture and strongly enforced by law, it still maintains a lot of power as a contract. Post This

- If low home prices make for stronger marriages, more investments in kids, and better school performance, policymakers need to look hard at local zoning regulations that serve mainly to make housing unaffordable. Post This

- Lower home prices also seem to lead to a higher number of kids, to kids being less likely to have to repeat a grade, and to lower chances of divorce. Post This

One of the great mysteries of the modern American family is why marriage has declined so much more among the poor than the rich. A new working paper from Jeanne Lafortune and Corinne Low provides a compelling theory with a good deal of evidence to back it up: When marriage is no longer strongly dictated by the wider culture and strongly enforced by law, it still maintains a lot of power as a contract—mainly for couples who will have assets to divide if they split up, and for couples where one parent sacrifices money-making opportunities to invest more time in raising kids. For these couples, marriage turns shared wealth into “collateral” in the event of a breakup.

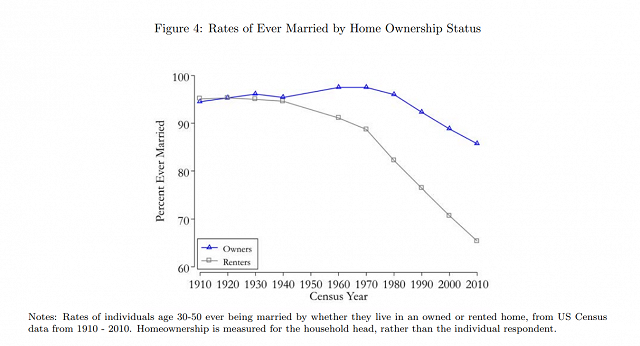

The economic logic here is strong, and it fits with the overall patterns in the data. For instance, here are marriage rates among homeowners and renters:

That doesn't prove much by itself, of course. We’re trying to explain a growing class gap, and everyone knows that richer people are more likely to own homes. But Lafortune and Low greatly buttress their theory with a string of additional analyses that rely on natural experiments.

The first involves home prices, which fluctuate in different places over time in somewhat random ways. When home prices are low, more couples are able to buy, and as a result more of a couple's income will go toward equity that will be split up—often given disproportionately to the lower-earning partner—in the event of a divorce. It turns out that when home prices are lower in the year a couple gets married, the couple is more likely to specialize, with the man working more and the woman working less, just as the theory predicts. This type of specialization would obviously be riskier without marriage, and, thus, the looming threat of divorce lawyers ensuring that the lower-earning partner gets a share of the wealth amassed by the other person if things go south. As expected, this effect is “absent for renters, and stronger for the college-educated,” who, thanks to their higher human capital, give up more money when they step back from their careers.

Lower home prices also seem to lead to a somewhat higher number of kids, to kids being less likely to have to repeat grades in school, and to lower chances of divorce. The authors’ results remain when they use a special statistical technique designed to eliminate some issues with their approach.1

My one concern with these results is that a link between home prices and most of these outcomes doesn't necessarilyprove the authors' theory. Owning a home or having lower mortgage payments might simply lessen financial stress on families, for example, allowing moms to scale back on their work if they want, and for couples to have more kids, and so on.

However, their second analysis shows that couples also behave differently depending on the nature of the contract that marriage represents. This is evident from both unilateral divorce and the strengthening of child-support enforcement for couples who were never married.

Unilateral or "no-fault" divorce laws debuted in different states at different times, which, like the quasi-random fluctuations in home prices, allows researchers to treat them as a natural experiment of sorts. These laws make marriage more like cohabitation in the sense that either party can leave at any time, but not when it comes to forcing the higher-earning partner to share the wealth in a breakup. As the authors put it, “having assets allows marriage to retain value—through increased commitment and protection for the lower earning spouse—even in the presence of one-sided divorce decision-making.” Indeed, no-fault divorce laws appear to strengthen the statistical link between asset-holding and getting married.

Stronger enforcement of child support for couples who never married, put into effect during the welfare reforms of the 1990s and made easier through efforts to establish paternity at the hospitals where women gave birth, also makes marriage and cohabitation more similar. Either way, the person who gets the kids is entitled to payments after a breakup. But these policies do not require the sharing of wealth above and beyond that. So, like no-fault divorce, such rules erode the benefits of marriage besides turning wealth into collateral, and this should strengthen the relationship between wealth and the decision to marry. This prediction is also borne out in the data.

This paper makes for fascinating sociology, but its findings also have policy implications. Most notably, if low home prices make for stronger marriages, more investments in kids, and better school performance, policymakers need to look hard at local zoning regulations that serve mainly to make housing unaffordable. They might also consider options for subsidizing homeownership outright, though this can have unintended consequences, including discrimination against renters and subsidizing some homeowners more than others.

No-fault divorce and child-support laws are less likely to be targets for reform, although both have been discussed by conservative thinkers for years. Some on the right have pushed back against no-fault divorce and set up private contractual alternatives, and in the 1990s, a few even argued that mothers should have no legally enforceable guarantee of child support from men they have never married. (See, for example, George Gilder, here and Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray, here.) These new results hint at some potential consequences of these moves, not all of which would be bad. Be that as it may, I don't think American lawmakers will be requiring people to stay in marriages they want to leave or letting never-married deadbeat dads off the hook anytime soon.

Lafortune and Low have made a serious contribution to our understanding of modern family dynamics. Their paper helps to explain why marriage has evolved the way it has, and it highlights some areas where public policy can make a difference. Both social scientists and policymakers should read it carefully.

Robert VerBruggen is an Institute for Family Studies research fellow and a policy writer for National Review Online.

1. Specifically, and a bit technically, the authors “instrument” home prices by leveraging the fact that these prices are more volatile in some regions than others.