Highlights

- The percentage of unmarried Americans who find porn morally acceptable increased 15 percentage points between 2017 and 2018—the largest increase among subgroups. Post This

- "The data show that persons who view pornography at younger ages are more likely to delay marriage,” according to Prof. Sam Perry. Post This

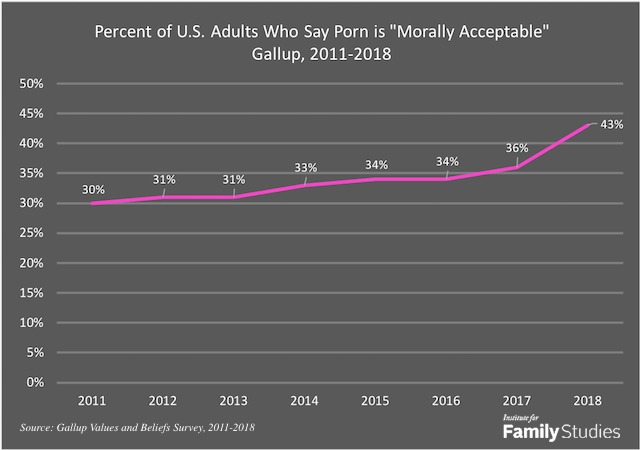

With free and unfiltered pornography continuing to expand its reach into our homes and everyday lives through smartphones, laptops, and streaming devices, it is not a huge surprise that more Americans today view porn as “morally acceptable” than in the past. But a recent Gallup poll shows that the percentage of Americans who say porn is “morally acceptable” has reached the highest level since Gallup first began asking the question in its annual Values and Beliefs survey in 2011. Although our beliefs about porn have been changing more slowly than other issues over the years, the percentage of Americans who believe porn is morally acceptable increased from 36% in 2017 to 43% in 2018.

"From 2011 to 2017, the percentage of Americans who find pornography morally acceptable rose by six points, whereas Americans' opinions on…other issues changed by an average of nine points," Andrew Dugan explained in the Gallup report. "But in light of this year's seven-point shift, perceptions that pornography is morally acceptable have increased more than any of the 16 other behaviors or practices Gallup has measured over the time span of 2011-2018."

According to Dugan, the seven-percentage-point increase between 2017 and 2018:

may represent something of an outlier, in which case acceptance of pornography would be expected to decrease next year, even if it remains above the 2017 level. Or the shift, though principally driven by a structural trend, may have been exacerbated by political factors, such as the public battle between Stormy Daniels and the president.

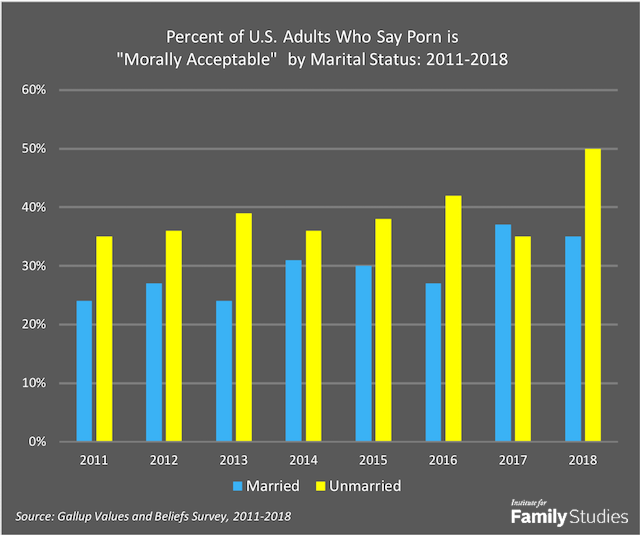

One of the more striking findings from this year’s survey is the gap between married and unmarried Americans that seems to be growing. The percentage of unmarried Americans who find porn morally acceptable increased 15 percentage points between 2017 and 2018—the largest increase among subgroups between 2017 and 2018 (the second largest increase was among men ages 18 to 49). At the same time, married Americans were the only group to stay about the same in their acceptance of porn (and experienced a small decline).

As the figure above shows, both groups have seen fluctuations in their acceptance of porn over the years, with an overall increase since 2011. And there has been a consistent gap between married and unmarried Americans since Gallup first asked about pornography in 2011, with a higher percentage of unmarried Americans saying porn is morally acceptable than married Americans every year except for 2017.

So, why the surge among unmarried Americans in 2018, and more broadly, why are married Americans generally less likely than unmarried Americans to consider porn morally acceptable?

I posed these questions to Sam Perry, an assistant professor of sociology and religious studies at the University of Oklahoma, who has authored or co-authored a number of large-scale studies on pornography use and relationship stability.

“Marriage as an institution demands a pretty high standard for fidelity,” Perry said. “In fact, there's evidence from the General Social Surveys over the past few decades that Americans are becoming more disapproving of extramarital sex than they were in years past.”

He continued that while he’s “interviewed dozens of students and adults who are permitted to view pornography in their dating relationships,” he sees this “a lot less often in marriage relationships, where one's spouse may take greater offense.” He added, “Being married could simply make one more likely to say, ‘Porn isn't a good thing for me, and probably not for anyone.’"

But what about the increase in the percentage of unmarried Americans who say porn is morally acceptable? According to Perry, this may be linked to the delay in marriage among young adults. “What's interesting to think about is that perhaps the causal arrow is reversed,” Perry pointed out. “Perhaps it's not being unmarried that makes people more inclined to think porn is okay, but that the more people think pornography is just fine, the less likely they are to get married.”

He is currently working on research that looks at this question and said, “the data show that persons who view pornography at younger ages are more likely to delay marriage.”

“Perhaps it's not being unmarried that makes people more inclined to think porn is okay, but that the more people think pornography is just fine, the less likely they are to get married.”

The theory that porn use is linked to a decline in marriage is one that University of Austin professor Mark Regnerus, the author of Cheap Sex, has also discussed on this blog. “At best, porn will augment—or compete with—sex, and stall marriage,” Regnerus warned. “At worst, sexual technology threatens to undermine coupled sex altogether.”

As to why viewing porn might lead young people to delay or resist marriage, Perry’s theory is that "pornography could either make marriage seem like an outdated, boring institution. Or pornography (and specifically masturbating to pornography) could remove the ‘need’ to get married as the source where one can find sexual fulfillment.”

This raises another question: what happens when at least some of these younger Americans do get married—what impact could more permissive attitudes about porn, not to mention longer years of porn use, have on their marriages?

The research on how pornography use affects long-term marriage quality and stability is probably best described as complex, with many questions still unanswered. Research conducted by Sam Perry and colleagues, which was covered on this blog by Nicholas Wolfinger, found that “men's pornography consumption has no statistically significant impact on marital stability, but porn does make divorce more likely when women watch it.” Wolfinger also reported that “porn affects marital quality differently than it affects marital stability,” citing another study by Perry in Archives of Sexual Behavior, which found that “relations are less harmonious when the man consumes pornography” compared to when a woman views it.

In at least three other recent studies Perry conducted, which he discussed in an extensive interview with IFS last year (see here and here), he found an association between pornography use and future marital dissolution. And in another study, Perry found that porn use by one partner especially weakens the quality of religious marriages.

Beyond marriage, other experts worry about the long-term impact of widespread pornography on the mental, emotional, and spiritual health of young people who are growing up in a porn-saturated world. A study by BYU professor and family therapist Mark Butler found a link between young people’s increasing use of pornography and their experience of loneliness and isolation. In a recent IFS blog post about his research, Butler suggested that pornography’s "potential to mislead and misshape young people’s views of women and men, relationships, intimacy, and sexuality during their formative years is very real—making a pornography-loneliness partnership a threat to their overall sexual and relational well-being.”

Of course, there are those who will argue that as porn becomes more morally acceptable to most Americans, it will cause less conflict between couples and therefore pose less of a relationship threat. But this view buys into the myth of porn as harmless entertainment with no long-term repercussions on how we see ourselves and others, how we view sex, and how we relate to each other. Moreover, it ignores the warnings of a growing number of relationship experts, feminists, lawmakers, and even some filmmakers who point out that easily accessible porn combined with earlier exposure poses a hazard to our collective sexual and relational health that deserves to be taken seriously for the good of future generations.

Alysse ElHage is Editor of the Institute for Family Studies blog. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.