Highlights

- A recent study claims that a popular provision of the Affordable Care Act reduced marriage and childbearing among 23-25-year-olds. Post This

- I’m a bit dubious of a 9% reduction in marriage driven by the availability of parental health insurance, but this paper is nonetheless an important contribution to a growing literature about the effects of Obamacare. Post This

One of the more popular provisions of the Affordable Care Act—also known as "Obamacare"—allows young adults to stay on their parents' health-insurance plans until they're 26. But if young adults rely on their parents more, they just might need each other a little less: A recent study claims that this provision of the act reduced marriage and childbearing among 23-25-year-olds.

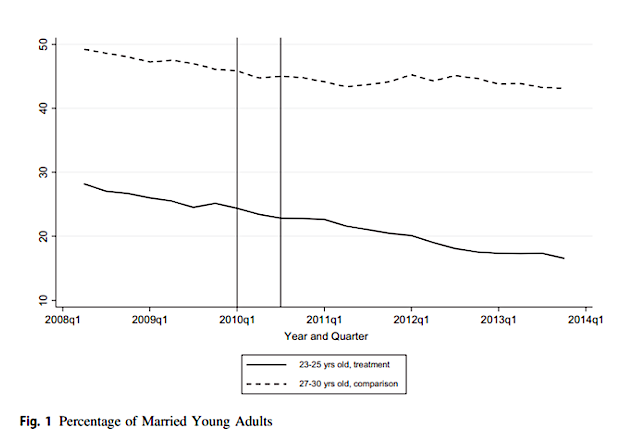

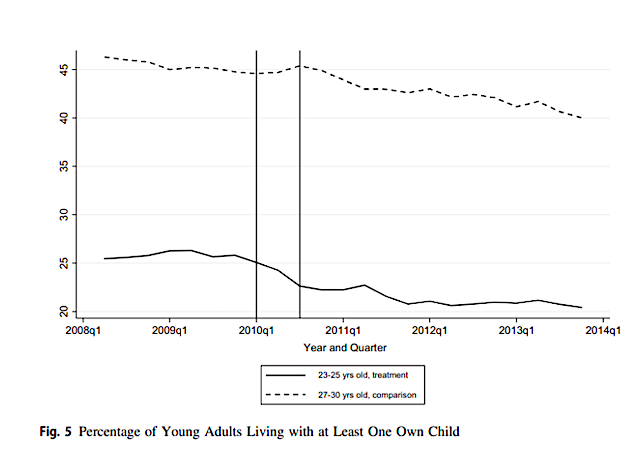

The effect is quite big. In the authors' statistical models, Americans in this age range became 2.4 percentage points less likely to be married thanks to the provision going into effect in 2010. Since only about 26% of these Americans were married to begin with, this suggests that the new provision may have delayed or prevented maybe 9% of the marriages for folks in this age group. For childbearing, measured by whether people lived with at least one of their own kids, the model finds a reduction of 1.6 points, or 6 percent. Young adults also became less likely to use assorted safety-net programs.

It's plausible that a lack of health insurance could create financial pressures to tie the knot and also limit access to contraception. Expanding insurance coverage could therefore have the opposite effects, as the paper suggests. But these results, especially the marriage one, are big enough to warrant skepticism, so let's take a closer look at how this research worked.

When sorting out what effect a policy had, a simple before-and-after comparison just won’t do. This is especially true in this case, because young adults' marriage and childbearing rates have been consistently falling for decades—a finding that they merely kept falling would not prove anything at all.

Instead, some kind of control group is necessary to tell help researchers determine what would have happened without the policy. For instance, researchers might compare trends in states that did and did not enact a new law, or states that did and did not already have a policy in effect when a new federal law imposed the policy nationwide. Unfortunately, though, these strategies aren't really possible here. This is a federal law applied nationwide all at once, and while some states already allowed kids to stay on their parents' insurance in certain circumstances, these rules were far more restrictive than the Obamacare policy.

So, the authors turn to a different control group: They compare trends for 23 to 25-year-olds with those for 27 to 30-year-olds, and they also include a wide variety of potentially confounding variables in their model. (Their data come from the 2008 Survey of Income and Program Participation, which followed up with participants through 2013, capturing data from various cohorts when they fell into the relevant age ranges in different years.) Since marriage and childbearing rates fell somewhat faster for the younger age group after the policy change, they conclude that the policy reduced those rates.

Clearly, the key assumption is that these two groups' rates would have moved in tandem over this period without the new insurance rule. That's a pretty big assumption, not only because Americans are increasingly delaying marriage and childbearing, but also because this time period was economically chaotic. It's hard to believe that the recession and its fallout affected these age groups equally, and statistically accounting for economic measures such as the age groups' unemployment rates can address this only imperfectly.

In anticipation of concerns like this, the authors point out that the two age groups did have basically parallel trends before the policy change. The first line in this chart represents when Obamacare first passed and some insurance plans voluntarily started enrolling more older kids than they used to; the second line is when the mandate officially and fully took effect.

Source: Chatterji, P., Liu, X. & Yörük, B.K. Effects of the 2010 Affordable Care Act Dependent Care

Provision on Military Participation Among Young Adults. Eastern Economic Journal 45, 87–111 (2019).

Here's a similar chart for whether respondents lived with any of their own kids:

Source: Chatterji, P., Liu, X. & Yörük, B.K. Effects of the 2010 Affordable Care Act Dependent Care

Provision on Military Participation Among Young Adults. Eastern Economic Journal 45, 87–111 (2019).

However, those are pretty short parallel trends, since the data begin in 2008, and not all parallel trends remain parallel even without a big new policy going into effect (again, especially during an otherwise chaotic period in which we might expect more people to put off marriage and kids for a few years). Further, the abrupt decline in living with children immediately following the passage of the policy is odd, considering it takes nine months or so to have a kid.

Before the Affordable Care Act, were there people in their early twenties who got married sooner than they otherwise would have—or even married people they otherwise would have left entirely—for the insurance? Probably, though I imagine few thought of it explicitly in those terms. It’s also probably true that being on their parents’ insurance made it easier for some young adults to use birth control, thereby reducing their fertility.

Whether you buy the study’s claims about the magnitude of these effects, however, depends on how much stock you put in the authors’ modeling decisions, including the comparison group of slightly older adults, the control variables, and the more technical choices as well. (These are “linear probability models,” which are somewhat divisive among social scientists.) I’m a bit dubious of a 9% reduction in marriage driven by the availability of parental health insurance, but this paper is nonetheless an important contribution to a growing literature about the effects of Obamacare on countless aspects of American life.

Robert VerBruggen is an Institute for Family Studies research fellow and a policy writer for National Review Online.