Highlights

- The effects from having a sibling depend on the outcome in question and the child’s birth order within the family, according to one study. Post This

- Children from large families are (on average) better behaved than children from smaller families. Post This

- In one study, adding a sibling did not reduce a child’s probability of exhibiting behavioral problems, and for first and second-born children it was associated with somewhat worse behavioral outcomes. Post This

Is it better for children to have siblings or not? Some people might think that the addition of a sibling means worse outcomes for a child, given that more children mean fewer parental resources available. Having had children myself, I am familiar with this kind of calculus. My husband and I were keenly aware how difficult it would be for us to afford private school for an extra child. Others think that the addition of a sibling means better outcomes for a child, as siblings can keep each other company and help each other out. For example, older siblings can help to educate and socialize younger siblings, as my two older brothers did with me.

Determining whether having siblings is advantageous for a child is complicated by the fact that larger families may differ from smaller families in ways that are important to outcomes. For example, the value systems of parents of big families may be different from the value systems of parents of small families, on average. The parents of small families may put a higher value on an extended education, as some of those parents are likely highly-educated people who are particularly concerned about their children’s educational achievement and have small families as a result.

A study published in the American Sociological Review addresses this question with over 30 years of data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NSLY), which contains information on the long-term cognitive and behavioral effects of adding a sibling for a representative sample of the biological children of U.S. women born between 1957 and 1964. Cognitive outcomes of each child were assessed using the Peabody Picture Vocabulary test that measures an individual’s vocabulary and is a good estimate of verbal ability and scholastic aptitude. Behavioral outcomes of the child were assessed by the mother and included measures of the child’s antisocial behavior, anxiety, depression, hyperactivity, dependency, tendency to be head-strong, and tendency to get into conflict with peers.

Using this data, the researchers were able to adjust for the effects of the family of origin (using fixed family effect models that allow them to exclude the effect of shared family factors, such as parental value systems and average parental intelligence). The researchers were also able to adjust for the fact that individual children within families differ in ways that are important to outcomes, such as child intelligence or individual personality. The analyses also adjusted for other factors that affect a child’s cognitive scores and behavioral outcomes, such as sex, age, race or ethnicity, family structure, mother’s education, mother’s work status, family income, and more.

The question of how a sibling affects child outcomes depends on whether you are most concerned with cognitive benefits or behavioral benefits, as well as the birth order of the child in question.

Overall, the researchers found that the effects from having a sibling depend on the outcome in question and the child’s birth order within the family. For cognitive outcomes, a sibling does decrease a child’s scores on cognitive tests, but only for first- and second-born children. These negative effects were less when children were more widely spaced apart. For third-born children and beyond, there was no effect of having a sibling on a child’s cognitive scores. Thus, whether the addition of a sibling is detrimental to cognitive outcomes depends on the child’s birth order within the family. But these results do support the idea that having fewer competitors for a parent’s attention and resources is beneficial for a child’s cognitive development.

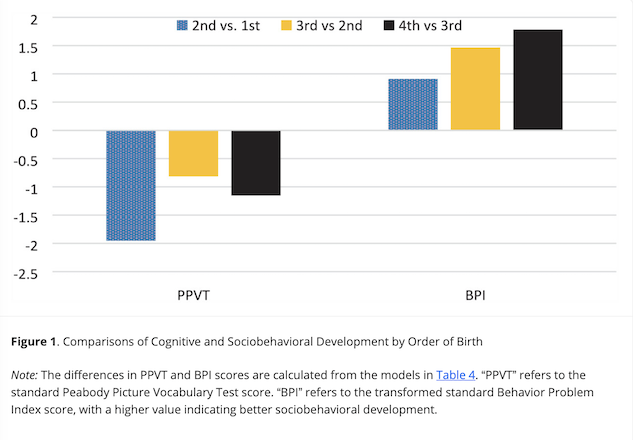

For behavioral outcomes, though, the story was different (see Figure 1). Adding a sibling did not reduce a child’s probability of exhibiting behavioral problems, and for first and second-born children it was associated with somewhat worse behavioral outcomes. However, later-born children had much better behavioral outcomes, on average. This suggests that older children do help to educate and socialize their younger brothers and sisters. Because in the population there are more children with older siblings from large families and fewer children with older siblings from small families, the overall effect is that children from larger families display less problematic behavior than children from small families, in general.

Thus, the question of how a sibling affects child outcomes depends on whether you are most concerned with cognitive benefits or behavioral benefits, as well as the birth order of the child in question. According to this study, adding a sibling is, on average, somewhat detrimental to the cognitive outcomes of first- and second-born children, especially if the children are spaced close together, but not for third children and beyond. When it comes to behavioral outcomes, while adding a sibling is generally slightly detrimental to the behavior of first and second children, subsequent children are much better behaved, with the net effect that children from large families are (on average) better behaved than children from smaller families.

Rosemary L. Hopcroft is Professor Emerita of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She is the author of Evolution and Gender: Why it matters for contemporary life (Routledge 2016), editor of The Oxford Handbook of Evolution, Biology, & Society (Oxford, 2018), and author (with Martin Fieder and Susanne Huber) of Not So Weird After All: The Changing Relationship Between Status and Fertility (Routledge, 2024).

*Photo credit: Shutterstock