Highlights

Far from having too many children, many women in developing countries, like their peers in the rich world, are actually having too few: that is, fewer children than they’d like to have.

This claim may seem strange: we’re used to hearing about the problem of excessively high fertility in Africa, or the unmet need for contraception. But while unintended or undesired pregnancies are indeed concerningly high in many developing countries, where contraceptive access could be improved, that’s only part of the story. At the same time, total fertility has often plummeted rapidly, even falling below desired fertility.

This claim has been nearly impossible to prove in the past for the simple reason that data on desired or ideal fertility has been hard to come by. None of the major international databases on fertility include any systematic, worldwide collection of data on fertility preferences. In layman’s terms, nobody has been systematically recording how many children women around the world actually want to have. This is shocking since women’s childbearing desires and ideals are widely recognized to have a big influence on fertility behaviors (duh!), and because governments and NGOs spend tens of billions of dollars every year on family planning programs domestically and abroad. But alas, around the world, policies intended to enhance reproductive rights and enable family planning are often enacted without any consideration of what women actually say they desire.

I have compiled a database from numerous sources on the average number of children a woman of childbearing age in a given country says is ideal to have. The exact question varies somewhat across time and country, but I have tried to focus on personal ideals to the extent possible. I generally prefer questions like, “If you had enough resources for it, how many children would be ideal for you, personally, to have?” Where questions about personal ideals aren’t available, I include general ideals. I do not include questions about intentions to maintain comparability. Overall, I have 727 data points, covering 141 countries, derived from 86 sources, reported in 63 different years, ranging from 1936 to 2018. That may sound like a lot, but the World Bank’s database on fertility has over 11,000 data points. In other words, even with numerous sources, I can only produce a very small database of fertility preferences compared to databases on actual fertility.

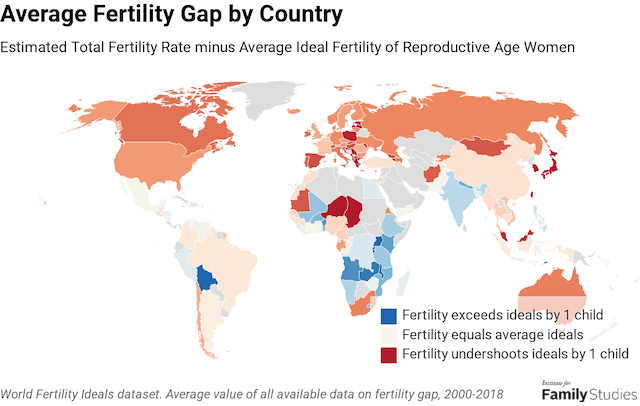

The map below shows (for each country for which I have any data) the gap between fertility preferences and the total fertility rate for any years with data between 2000 and 2018.

In the vast majority of countries, women can expect to have fewer children than those same women say would be ideal. This may be for any number of reasons: financial limitations, lack of a suitable partner, national instability, or infertility. And, of course, in some countries, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa, fertility rates do currently exceed women’s ideals, suggesting that improving contraceptive access remains vital to public health there.

But that situation is unusual. Most women around the world, even most women in countries outside of Europe and North America, are more likely to undershoot than overshoot their fertility ideals.

If this argument sounds familiar, it’s because I’ve made it before, in detail, for the United States. We have good data on this topic in America, and so can prove the argument very clearly. But the American situation, it turns out, is not unique! Around the world, it could be said that there is a lot more of a demand for children than there is a supply. One reason this fact is not widely understood is that—until now—there has been no global database of fertility preferences including both developed and developing countries. To the best of my knowledge, I am the first person to have done the legwork to combine existing, fragmentary databases, national statistical sources, international social surveys, and academic research. In most academic work, the experiences of rich and poor countries have been segregated, treating them like totally separate worlds. Poor countries, so the story goes, have problems with excess births, which requires help from international donors to provide contraceptives. Rich, democratic countries, meanwhile, aren’t usually thought to have a systematic reproductive rights problem at all.

But in reality, fertility has fallen so rapidly in the developing world that many poorer countries now face the same problems as Europe and America: women want to have children, but can’t make it work given the economic, social, and relational conditions facing them. Meanwhile, that problem, of missing kids, rather than just unintended births, is gaining more public attention.

Because much of the “population establishment” (as represented by the government and nongovernment organizations that organize conferences, coordinate donor money, and advise policymakers) operates from the mistaken assumption that most women have more kids than they want, they tend to give one-sided advice. When international NGOs talk about supporting women’s empowerment, or committing resources to family planning, or enhancing women’s sense of agency over their reproduction, they inevitably mean just one thing: helping women avoid unintended pregnancies. And, to be clear, that is valuable work. But it isn’t enough.

Population, reproduction, and family-oriented NGOs basically ignore the question of how to achieve desired births, not just avoid undesired births. Relatedly, major development benchmarks like the Human Development Index, or the Millennium Development Goals, do not even bother to include any metric of fertility desires in their standards.

This creates a vicious cycle. Governments and donors don’t collect data on fertility desires. Because the issue goes unmeasured, NGOs and civil society actors have little incentive to work for improvements in desire fulfillment. Because the people doing the yeoman’s work on family policy spend their day thinking about, for example, providing cheap contraceptives, rather than providing cheap diapers, they never push their governments to think more holistically about fertility. So, the cycle repeats. And the end result is that fertility settles well below the levels that women around the world say they want.

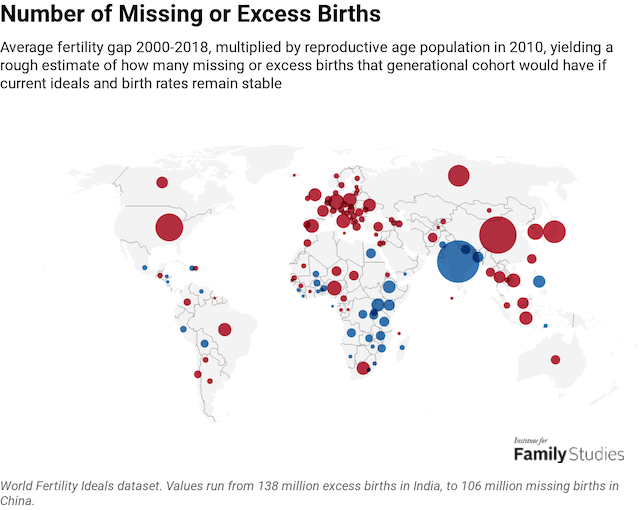

But it’s time for policymakers and researchers to wake up and address the problem. Missing-but-wanted children now substantially outnumber unwanted births. Missing kids are a global phenomenon, not just a rich-world problem. Multiplying out each country’s fertility gap by its population of reproductive age women reveals that, for women entering their reproductive years in 2010 in the countries in my sample, there are likely to be a net 270 million missing births—if fertility ideals and birth rates hold stable. Put another way, over the 30 to 40 years these women would potentially be having children, that’s about 6 to 10 million missing babies per year thanks to the global undershooting of fertility.

A very large amount of excess births come from India. A close look at India reveals, however, that fertility rates are falling a lot faster than desired fertility. In fact, around the world, countries with above-ideals fertility are getting rarer, so, if anything, this estimate of missing kids is an underestimate. The likely future for currently above-ideals fertility countries can be seen by looking at other comparable countries.

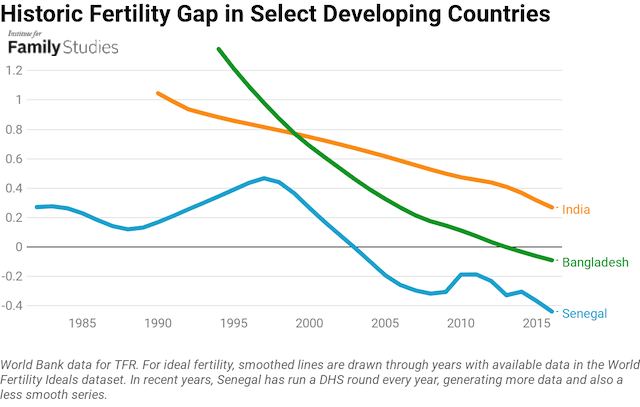

Senegal once had birth rates well above what women said they desired. But today, that is no longer true. Rapid declines in birth rates have sent fertility well below levels Senegalese women say is ideal, despite Senegal still being an extremely poor country. Bangladesh, likewise, has seen a switch from above-ideals fertility to (now) near-ideals fertility. It remains to be seen whether Bangladesh’s decline will continue or not, but India’s has appeared to accelerate in recent years.

It is reasonable for India to want to avoid above-ideals fertility rates: those are births women say they’d rather not have! But it seems unlikely that the decline will stop when the gap hits zero. More likely, it keeps falling, and Indian women within the next generation, or at most two, will experience below-ideals fertility.

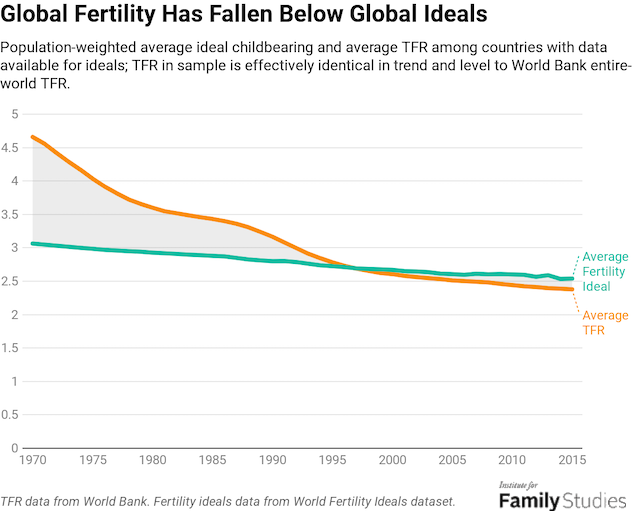

This issue isn’t unique to India. In fact, it’s global. Using the population-weighted average of TFR and fertility ideals for countries where data is available (which covers well over 90% of global population), we can see how global fertility ideals have changed over time.

While fertility ideals around the world do seem to be inching downwards, fertility is falling much faster. Today, fertility has slipped considerably below what the average reproductive-age woman says is her personal fertility ideal, and that gap continues to widen.

The problem of missing children is a serious problem. But it is understandable that many experts, governments, and non-governmental organizations are unfamiliar with this problem since the relevant data collection has been scattered and infrequent. Furthermore, because most of the twentieth century was characterized by above-ideals fertility, the idea that global fertility might durably drop below what women desire seemed farfetched. But that is where we are today. And since we now live in a world with a growing global shortfall in births, it is incumbent on the policymaking community to take the problem seriously, and look for solutions.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, and an Adjunct Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

Note: The World Fertility Ideals dataset is available for distribution upon request, and identifies data sources.