Highlights

- New research shows that possession of means still matters when it comes to marriage and family formation for men, but not for women. Post This

- For men, as income increases, the probability of marriage also increases such that men in the highest income category are about 57 percentage points more likely to marry than men in the lowest income category. Post This

It was in nineteenth century Britain that Jane Austen penned the words “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” In those days, a man with a good fortune was also likely to actually find a wife, as possession of means was prerequisite for marriage for men at that time. That was how it was then, but what about today? In 21st century America, over half of all married couples are dual-earner families, and men are no longer expected to be the sole source of financial support for their families. It seems, therefore, that possession of means would no longer matter as much for men’s marriage prospects, while at the same time it may matter more for women’s marriage prospects. Yet my new research, published in the journal Evolution and Human Behavior, shows that possession of means still matters when it comes to marriage and family formation for men, but not for women.

This research uses data from a large probability sample (55,281) of the U.S. population collected by the Census Bureau—the 2014 wave of the Study of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). The SIPP data contains information on men’s and women’s personal incomes from all sources (which includes income from all sources, not just wages, plus investment and business losses so it can be negative), in addition to the number of marriages and number of biological children.

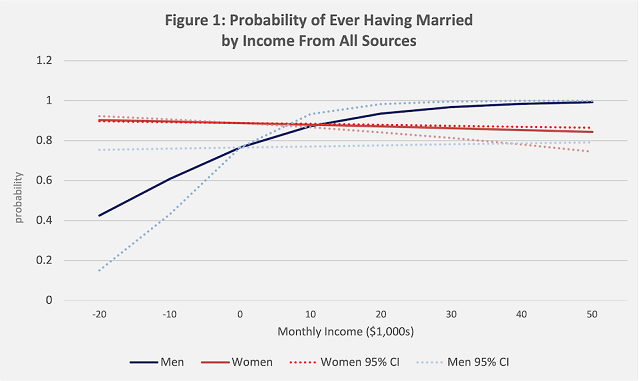

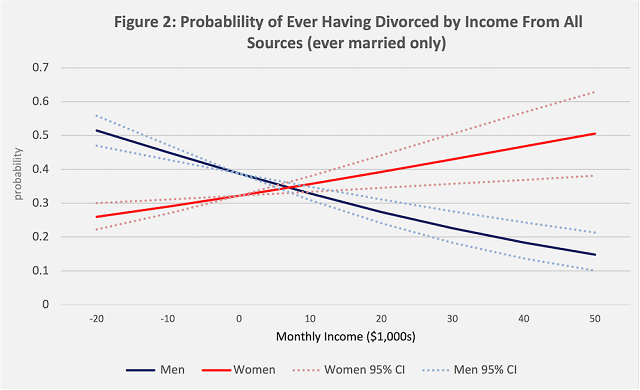

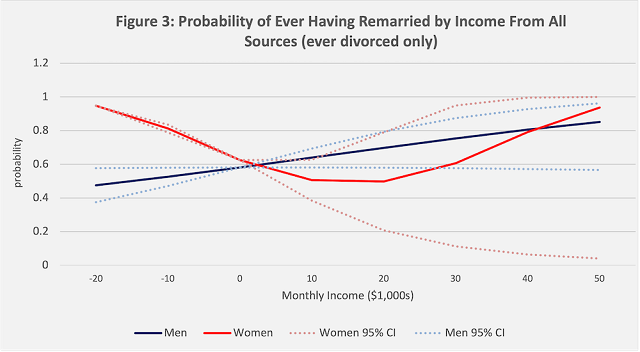

The results of the study are shown in Figures 1 through 3, which depicts the probability of marriage, divorce, and remarriage for men and women by personal income, adjusting for age, income, education, race, and Hispanic ethnicity. The solid lines give the probability; the dotted line gives the 95% confidence interval for the probability.

As Figure 1 illustrates, for men, as income increases, the probability of marriage also increases such that men in the highest income category are about 57 percentage points more likely to marry than men in the lowest income category. The same is not true for women. High income men are more likely than low income men to marry, while income is unrelated to marriage for women. Given that marriage involves choice on both the man and the woman’s part, these results suggest that women are more likely to choose to marry men with good financial prospects, while a woman’s financial prospects are less important to men when choosing a marriage partner.

Note: *Model prediction with age, education, proportions Black and Hispanic set to their means.

Not only are high-income men more likely to marry, they are more likely to stay married, too. Figure 2 shows the probability of divorce for those who have been married at least once, and reveals that for men the probability of divorce declines as income rises, such that men in the highest income category are about 37 percentage points less likely to divorce than men in the lowest income category. For women the probability of divorce increases as income rises, perhaps mostly due to reverse causality and the fact that divorced women are more likely to have to support themselves financially. For men, the results suggest that women are more likely to divorce low income men than high income men.

Note: *Model prediction with age, education, proportions Black and Hispanic set to their means.

High-income men are also more likely to be “recycled” in the marriage market. Figure 3 shows that if high-income men do divorce, they are more likely to remarry than low-income men. Men in the highest income group are about 38 percentage points more likely to remarry than men in the lowest income group. Once again, this suggests that high-income men are valued as long term mates by women. High-income women, on the other hand, are less likely to remarry than low-income women. This is not true for the very highest income women, but the confidence interval is very wide for these women, suggesting that this finding is less certain. These results further suggest that partner earning capabilities are less important in male mate choice than in female mate choice.

Note: *Model prediction with age, education, proportions Black and Hispanic set to their means.

Not only are high-income men more marriageable than other men, my study also found that they are more likely to become biological fathers: the results show that high-income men are more likely to have children than low-income men. Men in the highest income group are about 41 percentage points more likely to ever have children than men in the lowest income group. The opposite is true for women—high-income women are more likely to be childless. For women, there is once again reverse causation here, as women with children are more likely to work part time or not at all. Women with children may also be subject to discrimination by employers. There may be some reverse causation for men as well—men may work harder and earn more money once they have a child. Alternatively, married men with children experience positive discrimination by employers and may be more likely to be hired and promoted.

Income does not affect repeat fatherhood, however, according to the study. Men who remarry after divorce do tend to remarry relatively younger women, but this does not vary by personal income. While higher income men are more likely to remarry and marry younger women, if they already have children, they are not more likely to have additional children with their new wives. For women with children who divorce, high income is associated with a lower probability of having additional children with new partners.

These results provide evidence about who men and women are most likely to choose to marry and have children with. The results reveal preferences regarding long term mates, and these preferences suggest that women continue to prioritize financial prospects while men do not. Of course, it may not be that most women place a high value on a man’s finances; rather it may be that women value the characteristics associated with income earning, such as industriousness, conscientiousness, and intelligence. Regardless, the results are behavioral evidence that men and women today prefer somewhat different things in a long-term mate. All in all, this evidence suggests that modern American men and women are not as different from their nineteenth century forbears as we might like to think.

Rosemary L. Hopcroft is Professor of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She is the author of Evolution and Gender: Why it matters for contemporary life, Routledge 2016) and editor of The Oxford Handbook of Evolution, Biology, & Society (Oxford, 2018).

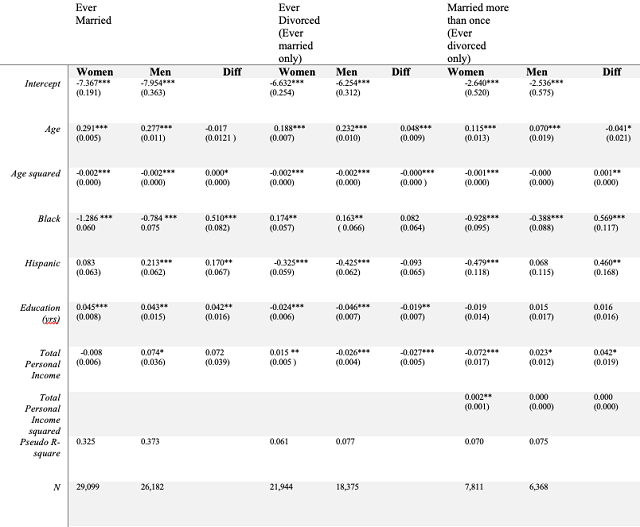

Appendix 1. Logistic regression of ever having been married, ever having been divorced

and ever having remarried.* Logistic regression coefficients, standard errors in brackets.

*p < 0.05 **p<0.01 ***p<0.001 *Not shown – controls for state of residence