Highlights

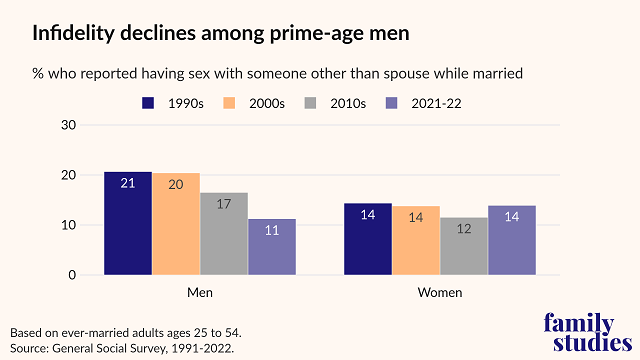

- In the 1990s and 2000s, about 1 in 5 ever-married men reported engaging in extramarital sex. That share fell to 17% in the previous decade and has continued to drop in recent years. Post This

- Men in high-prestige occupations—think CEOs, physicians and surgeons—are generally more likely than others to have cheated on their spouse. Post This

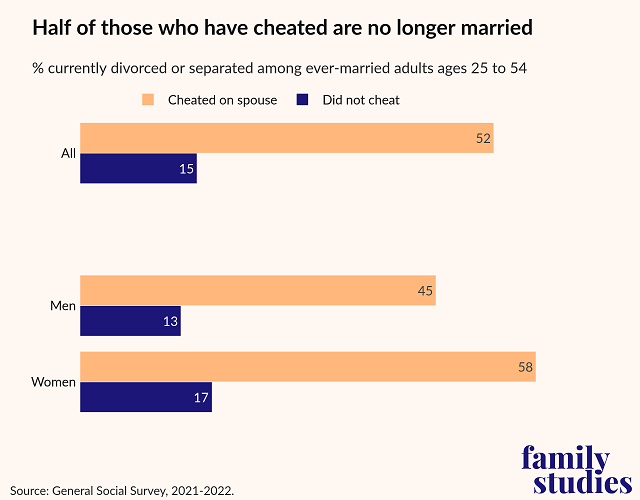

- Among ever-married, prime-age adults who have cheated on a spouse, about half are currently divorced or separated. Post This

A kiss-cam moment at a recent Coldplay concert went viral: a tech company CEO was caught on camera embracing a woman who was not his wife, an HR executive at the same company. The story spread like wild fire, and that public display of infidelity stirred up many conversations on men, women, and cheating—raising questions that are worth exploring with data. How common is cheating today? Are men with higher status jobs more likely to cheat? How does work status relate to cheating?

To better understand cheating among adults in the workplace, I looked at the data from the General Social Survey (GSS) for men and women ages 25 to 54, the prime age range with the highest rate of labor force participation. I combined the data in each decade to be able to look beyond fluctuations in a single year and focus on the overall trend.

Overall, we see a decline in the share of cheating among ever-married, prime-age Americans. Between 1991 and 1998, 17% of adults in this group reported that they’ve had sex with someone other than their spouse while married. The share declined to 14% between 2010 to 2018, and further to 13% in the most recent data available from 2021 to 2022.1

This decline is much more pronounced among prime-age men. In the 1990s and 2000s, about 1 in 5 ever-married men reported engaging in extramarital sex. That share fell to 17% in the previous decade and has continued to drop in recent years. In contrast, the share among ever-married, prime-age women has remained relatively steady over time. As a result, rates of cheating are now roughly equal between prime-age men and women.

Are Higher Status Men More Likely to Cheat?

Men in positions of higher status may be more prone to infidelity, as status is often seen as an attractive trait and typically comes with more opportunities for extramarital encounters. Studies of professionals have shown power is indeed linked to more infidelity, and those in higher positions are more likely to be unfaithful.

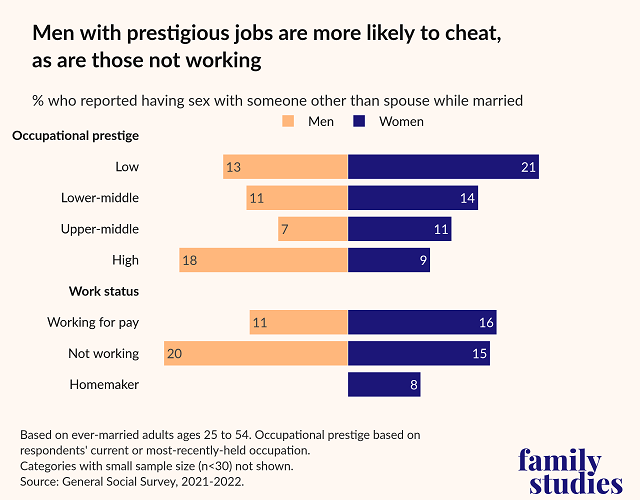

Occupational data from the GSS tells a nuanced story about infidelity. Men in high-prestige occupations—think CEOs, physicians and surgeons—are generally more likely than others to have cheated on their spouse. Nearly 1 in 5 prime-age men with high prestige jobs (18%) have had extramarital sex, compared with 7% of men in upper-middle prestige jobs, and 13% of men in low prestige occupations. However, this pattern doesn’t apply to women in similar positions. In fact, women in low-prestige jobs are more likely to have cheated than those with high-prestige jobs (21% vs. 9%). (For more information about the occupational prestige classifications, see the Appendix.)

Infidelity is also linked to employment status. In this case, men who are not working are more likely to have cheated on their spouse.2 About 1 in 5 men ages 25 to 54 who are not employed have cheated, compared with 11% of men who work for pay (full time or part time). For women, the pattern is different. The cheating rate is similar among women who work and those who do not work. However, women who stay home to care for children and manage the house are least likely to cheat, with 8% reporting infidelity, compared with 16% of women who work for pay. (Comparable data for men in this group is not available due to limited sample size.)

The connection between infidelity and men’s work characteristics is intriguing, with some possible explanations. Previous research shows that women often find dominant or prestigious men more attractive for long-term romantic relationships, which could create more opportunities for men in these positions to cheat. On the other hand, as men’s work is often tied to their sense of identity and masculinity, failing to meet these expectations (e.g., unemployment or underemployment) can threaten masculinity. In response, some men may seek validation through outside relationships. Indeed, one study found that men who are financially dependent on their wives or cohabiting girlfriends are five times more likely to cheat than men earning comparable incomes to their partners.

Who Cheats More?

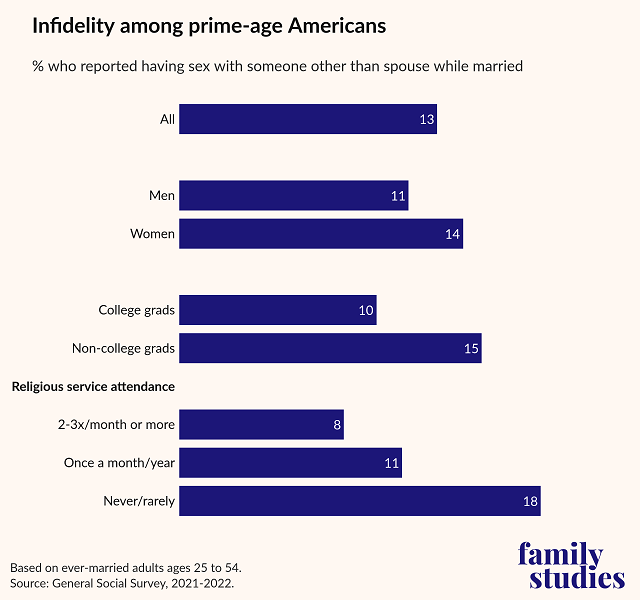

Infidelity varies across demographic groups, and men typically are more likely than women to cheat. However, this pattern does not hold up among prime-age Americans. According to my analysis of the latest GSS data on ever-married adults ages 25 to 54, men are no more likely than women to report infidelity. Some 11% of men and 14% of women say they have cheated while married, and the difference is not statistically significant.

A few patterns remain consistent among prime-age, ever-married adults. Those with a college education are less likely than those without one to cheat (10% vs. 15%). Religious practice also plays a significant role in cheating: adults who regularly attend religious services are much less likely to have cheated than those who never or rarely attend (8% vs 18%).

It is also worth noting that that rate of cheating is much higher among divorced or separated adults (34%) than those who are currently married (7%)—likely because those who cheated on their spouse are more likely to end up divorcing.

In fact, infidelity is a major contributing factor to divorce. Previous research based on small-scale interviews of divorced individuals suggests that a majority cited infidelity as a reason for their divorce. More importantly, infidelity was often mentioned as the breaking point in an already deteriorating relationship, the “last straw,” so to speak.

My analysis based on the new GSS data suggests that among ever-married prime age adults who have cheated on a spouse, about half are currently divorced or separated. And those who cheated on their spouse are about three times more likely than those who didn’t to be divorced or separated (52% vs. 15%).

Compared with prime-age women, men who have cheated are less likely to be currently divorced. Fewer than half of men who have been unfaithful (45%) are divorced, whereas nearly 60% of women who have cheated on a spouse are divorced.

A couple of factors may help explain this gender difference. Previous research based on a sample of undergraduate students suggests that men find it more difficult to forgive sexual infidelity, and they are more likely than women to end a relationship following a partner’s cheating. If this holds true within marriage, then when a woman cheats, the marriage is less likely to survive.

At the same time, as I previously pointed out, men are also more likely than women to remarry. It is possible that some currently married men who have cheated are now in their second marriage, as the data doesn’t tell us whether the person who cheated is still married to the same spouse.

As for the "kiss cam CEO"? He may still have a shot at salvaging his marriage if his wife is forgiving. But based on what we’ve seen so far, the odds don’t look promising.

Wendy Wang is Director of Research at the Institute for Family Studies.

*Photo credit: Shutterstock

1. The GSS shifted from in-person interviews to online and mixed modes in recent years (2021,2022), which may complicate the interpretation of trends.

2. Not working” and “not employed” are used interchangeably to refer to a group that includes mostly unemployed adults, along with a small number of retirees, students and respondents who selected “other” for their employment status in the GSS.

3. Table note: Based on occupational prestige score (prestg10) in the General Social Survey. For more details, please see Page 3307 in GSS codebook, Appendix F.

Appendix

Table: Occupational Prestige by Four Categories3

| Category | Prestige Score | Examples |

| Low Prestige | 0–35 | Less prestigious jobs (e.g., janitors, food service workers, cashiers) |

| Lower-Middle Prestige | 36-49 | Routine or entry-level occupations (e.g., truck drivers, secretaries, retail sales) |

| Upper-Middle Prestige | 50–64 | Skilled or semi-professional roles (e.g., police officers, K–12 teachers, technicians) |

| High Prestige | 65–80 | High-status professions (e.g., physicians, lawyers, college professors, executives) |