Highlights

- When U.S. states provide subsidies for IVF, overall fertility rates are unaffected, in general, because while fertility rises for older women, it falls for younger women. Post This

- Individuals who would probably have the most use for IVF also tend to have lower fertility desires. So IVF subsidies don’t seem like a plausible avenue for boosting society-wide fertility. Post This

- Society-wide fertility is unlikely to be increased by interventions aimed at 40-something women having a first child. Post This

Recently, President Trump proposed that insurance companies be required to cover in vitro fertilization (or IVF), so it’s worth asking: does subsidizing IVF boost fertility?

As this brief will show, the answer is no. Free IVF has no effect on fertility.

Why IVF Subsidies Don’t Work

Before getting into the heart of this issue, it’s important to address a background question: what is the goal of subsidizing IVF? There are a lot of possible goals. My wife and I have struggled with infertility, ultimately overcome through the wonders of modern medicine (but not, as it happens, IVF). Helping people suffering from infertility is an important endeavor. If the goal is to alleviate suffering, IVF subsidies could be one way to do that.

But in his comments, President Trump said the goal of his proposal was “because we need great children, beautiful children,” which seems to suggest, especially in combination with vice-presidential candidate J.D. Vance’s public comments on pronatal policy, a belief that IVF will boost fertility. Unfortunately, IVF subsidies are not the way to achieve this goal. That’s because they don’t work, and they don’t work for the exact reason they are popular: such policies overwhelmingly help older women have a first birth. This is a laudable outcome, but older women facing fertility challenges are implausible candidates to help propel society-wide fertility higher. In 2022, just 0.5% of births to women ages 25-29 involved IVF, compared to 55% of births to women ages 50 or older. And whereas just 4% of non-IVF births were to women aged 40 or older, 23% of IVF births occurred among women in their forties or older. Additionally, most IVF users do not have high odds of going on to have more children: whereas 2.3% of first births in 2022 involved IVF, just 1.8% of second births and 0.9% of third births did. Society-wide fertility is unlikely to be increased by interventions aimed at 40-something women having a first child.

The other group most impacted by IVF subsidies is, of course, gay and lesbian couples. But, in a large, not-yet-published survey we recently conducted at IFS, 36% of gay and lesbian individuals reported desiring zero children, compared to only 14% of heterosexual individuals; much lower shares also reported desiring 3 or more children. In other words, the individuals who would probably have the most use for IVF also tend to have lower fertility desires. So, again, IVF subsidies don’t seem like a plausible avenue for boosting society-wide fertility.

Finally, we should consider what happens when IVF becomes more readily available. While more people, especially older individuals, would gain new options to boost their fertility, younger people would also gain those options, and as a result might possibly change their fertility behavior in expectation of using IVF in the future. Imagine if it suddenly became possible for individuals to have children at age 60. Some 60-year-olds might have kids, but also some 39-year olds might delay having kids, believing they have plenty of time (especially if their employers aggressively advertise free egg freezing to them). IVF not only helps older people have kids, but it also makes it easier for younger people to delay kids.

So, as we look at the empirical evidence, we should explore what happens to fertility at different ages.

What Happens When States Subsidize IVF?

Many states already subsidize IVF, so we have high-quality empirical studies on the effects of those subsidies in the real world. The table below summarizes those studies:

Summary of Studies on IVF Insurance Coverage Mandates

Across four studies with six different family-related outcomes measured, one study didn’t report an overall effect, but found approximately offsetting changes in fertility rates of women under and over age 35. Another study found effects on delayed marriage. Two studies found no overall effect on first birth rates: one of them found an increased rate for women over 35 and no effect on women under 35; the other found a reduced rate on women under 35 and no effect over 35. Remember, though: first births are not all births, and studying only first births is a way of stacking the deck in favor of IVF, since IVF disproportionately impacts first births. The one study that analyzed a wide range of endpoints found no effect on overall first birth rates or on increased age at first birth, and no effect on completed fertility.

Overall, we see that when U.S. states provide subsidies for IVF, overall fertility rates are unaffected, in general, because while fertility rises for older women, it falls for younger women.

More Recent Cases

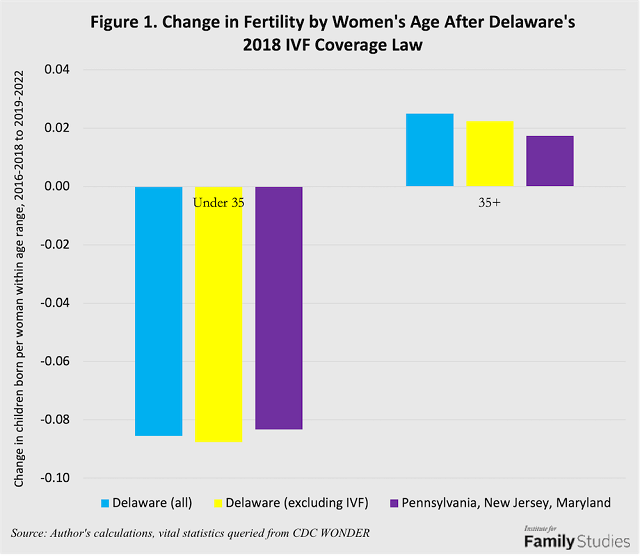

For what it’s worth, it’s easy to see that these policies simply cannot have big effects. The studies above all predate 2018, when Delaware implemented a comprehensive IVF coverage law, so Delaware is not included in their sample of states with IVF coverage. What happened to fertility in Delaware before and after IVF coverage? Well, we can look at age-specific fertility rates in Delaware from 2016-2018 vs. 2019-2022, and see how they changed compared to nearby states, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and New Jersey.

As the figure shows, the effects are extremely small. Birth rates for women under age 35 fell in Delaware and nearby states, but ever-so-slightly more in Delaware during these time periods. Birth rates rose among women over age 35 in both areas, but by slightly more in Delaware. On net, Delaware’s IVF law may have possibly increased fertility by, at most, 0.005 children on average. Not 0.5 children: 0.005.

We can verify these small effects because Delaware reports the number of children born as a result of IVF. Estimated total fertility rates before age 35 fell 0.002 children more for women under 35 excluding IVF than it did including IVF, and children born after age 35 rose by 0.003 children, meaning the increase in IVF is associated with a 0.005-child increase in Delaware’s fertility. Two different methods yield the same result: free IVF boosted fertility by such a small amount it is virtually undetectable.

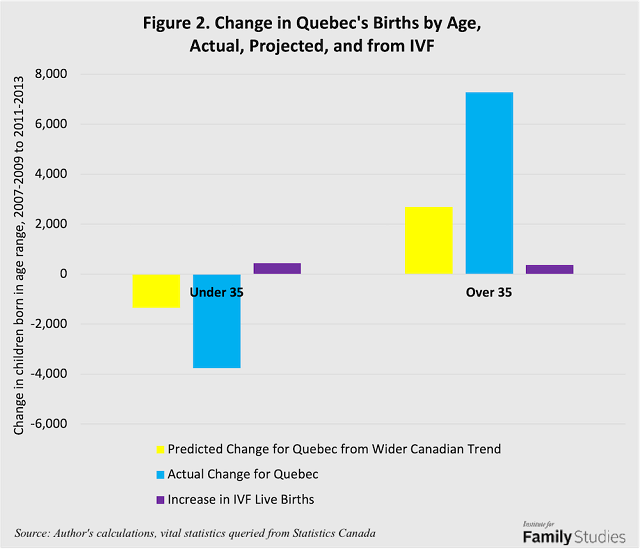

We can look at another case: Quebec. In 2011, Quebec dramatically increased the public subsidy available for IVF, with the result that IVF usage almost tripled. We can compare birth rates by age in Quebec from 2007-2009 to those in 2011-2013, and see what they would have been if they had shown a similar trend as the rest of Canada, and how much of that gap can be explained by live births from IVF.

Quebec’s births for women under age 35 declined much more than might have been guessed from the wider Canadian trend, even as likely births from IVF cycles under age 35 rose by around 400 births. Meanwhile, Quebec’s births for women over age 35 also rose by much more than might have been expected: but again, only about 400 births came from IVF. If we assume that none of those likely IVF births replace counterfactual non-IVF births, Quebec’s increase in IVF subsidies boosted fertility by just 0.005 children per woman, similar to Delaware. Of course, that’s assuming that the entire increase due to IVF subsidies involves extra births that would not have occurred otherwise, which may not be the case.

Conclusion

If the goal is to boost births, subsidies for IVF are a peculiar kind of policy. They disproportionately go to people unlikely to have additional births beyond the first birth, and only subsidize very specific subsets of individuals and families with specific values (i.e. people without ethical objections to IVF), and they may incentivize fertility delay among younger couples.

On the one hand, it’s not surprising that IVF subsidies are gaining popularity: infertility is a legitimate medical condition worth treating. Politicians who fear that the public won’t stomach direct support for family life may gamble that the public will support fertility subsidies masquerading as health interventions. Moreover, couples struggling with infertility garner obvious and well-deserved sympathy, and academic research shows that infertility has significant mental health costs. And since the fertility industry is increasingly attracting investment from Silicon Valley into pricey procedures, including eugenic embryo selection via IVF, there are no shortage of lobbyists willing to encourage politicians to support these policies.

But IVF subsidies are essentially a form of Potemkin pronatalism: they may sound pronatal but the supposed benefits do not really exist. The main effect of IVF subsidies is just a transfer of money away from some types of families (especially people who marry young, who tend to be lower income) to other types of families (especially those who marry late and tend to be higher income, or LGBT couples with a wide range of incomes), without any net effect on overall fertility, and perhaps an intensification of fertility delay. Subsidies for IVF may be justifiable for health reasons, or on the basis of supporting couples who can’t have kids any other way, or they may be unjustifiable on moral or ethical grounds, or because they subsidize wealthier families more, but these questions are outside the bailiwick of pronatalism. However, on the simple question of “Will subsidizing IVF increase fertility?” the simple answer is “no.”

Lyman Stone is a senior fellow and director of the Pronatalism Initiative at the Institute for Family Studies. He is also the chief information officer of the consulting firm Demographic Intelligence.