Highlights

- It is too early to say for certain but growing numbers of actual and would-be parents seem to be heeding the conventional wisdom that a stable two-parent family helps children flourish. Post This

- One of the most encouraging developments is the rebound in the proportion of black children being raised by their biological fathers as well as their birth mothers. Post This

All the experts agreed: the nuclear family was on its way out. The two-parent family of married mother and father bringing up their own biological children would soon be replaced by a menagerie of alternate family forms: cohabiting couples with children; single-parent families; blended families; same-sex couples raising children conceived and born in a variety of unconventional ways; and so on. And for more than a half-century, each year’s tabulation from the Census Bureau on children’s living arrangements seemed to be proving the experts right.

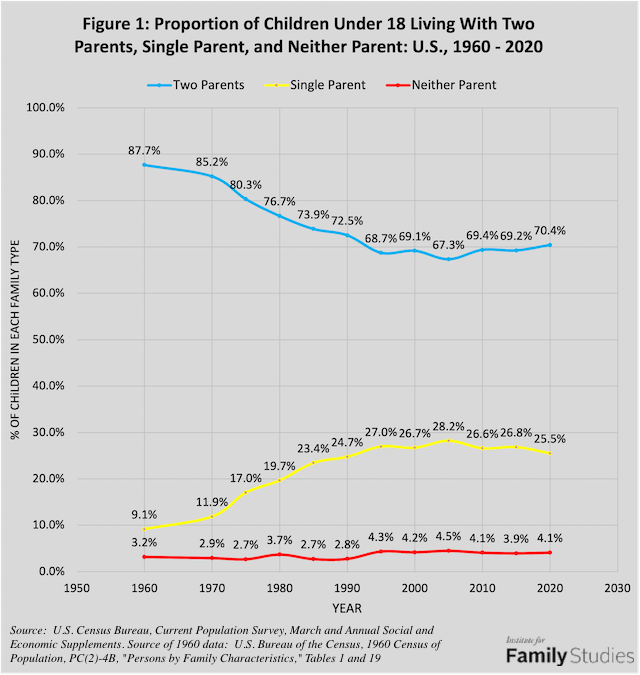

As may be seen in Figure One, the Census Bureau’s reading of the proportion of children under 18 living with two parents declined from 88% in 1960 to just over two-thirds in 2005. And the proportion living with divorced, separated or never-married single parents tripled from 9% to 28%, while the fraction living with neither parent (that is, with grandparents, other relatives, or foster parents) inched up from 3% to 4½ percent.

But a funny thing happened on the way to extinction: although certainly not out of intensive care, the supposed corpse of the two-parent family seems to be breathing new life. The proportion of children living with two parents has gradually recovered, reaching 70% in 2020. And the fraction living in one-parent families has slipped from 28% to 25%, while the number living with neither parent has levelled off between 4 and 5 percent.

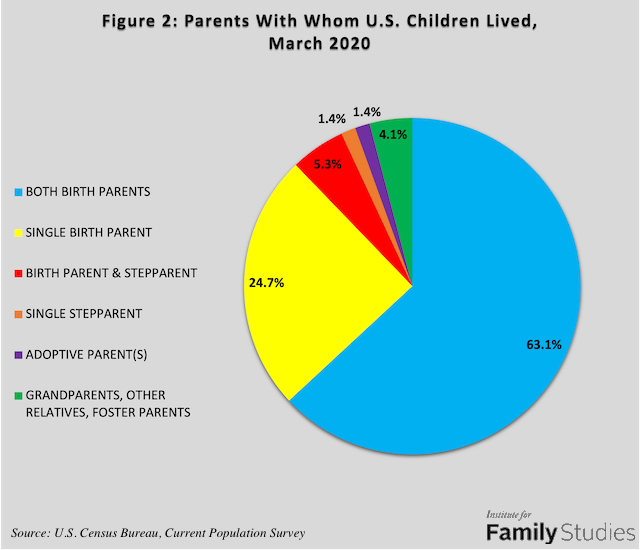

Before celebrating the turning of the tide, however, please note that the standard Census Bureau family trend charts underestimate how grave the condition of the two-parent family has been and still is. The Bureau lumps stepparent and adoptive families with both birth-parent families, making their two-parent category more inclusive than commonly understood. Furthermore, children in stepfamilies and adoptive families have experienced family disruption. The evidence is that they have higher rates of emotional, behavior, and learning problems than those residing with both birth parents.

Using a new online tabulation facility that the Census Bureau has made available to researchers, I carried out a special tabulation of data from the latest Current Population Survey to give a more detailed breakdown of children’s family living arrangements in 2020. The results are shown as a pie chart in Figure Two. As may be seen in the figure, the proportion of children living with both birth parents was just over 63%, while the proportion living with a single birth parent was just under 25 percent.

Although lower than the 70% figure cited above, 63% actually represents a small increase from what the proportion of children living with both birth parents was in 2012, when it was 61 percent. And the 25% living with single, biological parents represents a small decline from the 2012 proportion of 28 percent. So even with this stricter definition of two-parent families, the trend data show a recovery or at least a levelling off from the lows observed early in the new millennium.

Intact Family Throughout Childhood: A New Estimate

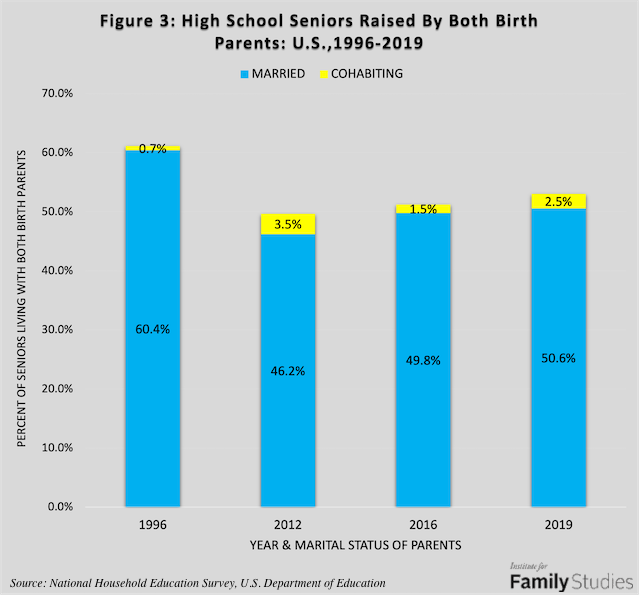

How many American children not only lived with both birth parents at a given point in time but were raised by both birth parents throughout their childhood? One way of estimating this proportion is to examine the living arrangements of high school seniors. The fact that seniors were still living with both birth parents at the culmination of their schooling means that the vast majority grew up with them since birth. Some may have been born to unmarried parents who subsequently got married during the student’s childhood. Some may have experienced parental conflicts or temporary separations, but not the kind of conflict that resulted in permanent splits. Their parents were able to work things out and the marriages endured.

The necessary information to produce such an estimate is available from the National Household Education Survey, the latest round of which was carried out in 2019 and data which were recently released by the U.S. Department of Education. The results of my analysis of the public use file from that survey are shown in Figure Three, with results from earlier rounds shown for comparison.

In 2019, just over 53% of U.S. high school seniors were living with both their biological parents. Just under 51% were with married birth parents and 2½% with cohabiting parents. This represents a considerable decline from the situation in 1996, when 61% of seniors were living with and had been raised by both birth parents. But it represents a modest recovery when compared with parallel findings from 2012 (when under 50% lived with both birth parents) and 2016 (when 51% did). Once again, the newest data point to a turning tide.

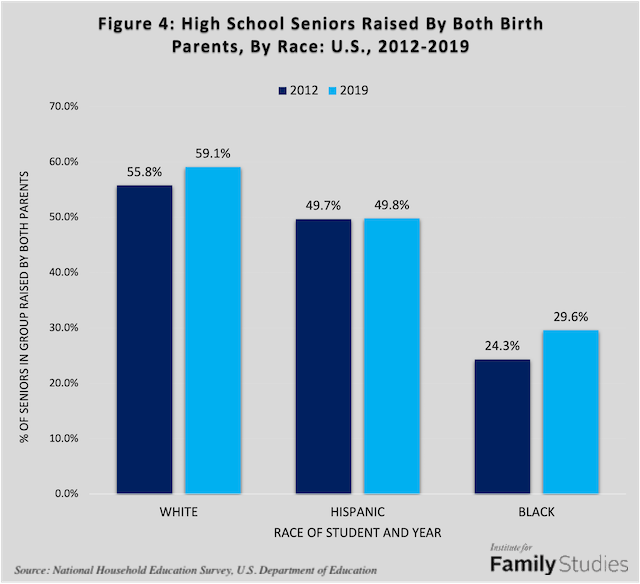

One of the most encouraging developments is the rebound in the proportion of black children being raised by their biological fathers as well as their birth mothers. Among African American high school seniors, that proportion has risen from 24% in 2012 to 30% in 2019. (See Figure 4).

It is too early to say for certain but growing numbers of actual and would-be parents seem to be heeding the conventional wisdom that a stable two-parent family helps children flourish educationally, socially, and economically. They have come to accept that loving and being loved by one’s two parents, who are also committed to one another, has benefits for the children and adults involved and for the community in which they live.

Nicholas Zill is a research psychologist and a senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies. He directed the National Survey of Children, a longitudinal study that produced widely cited findings on children’s life experiences and adjustment following parental divorce.