Highlights

Too many American children experience the hurt from broken bonds at an early age. About 35% of American adolescents live without one of their parents, and around 40% of American children are born outside of marriage. Although these kids’ parents are usually in a relationship or even cohabiting at birth, mom and dad often break up while their child is still young.

Of course, if the biological parents of a child split up, the child in question will usually continue to reside with the mother. And although many of these children continue to have a close relationship with their father, this is the exception and not the rule, especially when it comes to children whose parents were never married in the first place.

In other words, the problem of broken families is interchangeable with “fatherlessness.” Simply put, father-absence is the now-widespread phenomena of children who have no close relationship with, or even knowledge of, their biological father. Only 9% of children were raised without their father in 1960, yet today a quarter of American kids are raised without their father. The consequences are far from benign.

Family Structure and Poverty

First, family breakdown fuels poverty. On average, even high school dropouts who are married have a far lower poverty rate than do single parents with several years of college.

But family structure has the biggest impact on children. According to Raj Chetty—the preeminent researcher on the topic of social mobility—having fathers in the neighborhood is a primary factor in predicting upward income mobility for the children in that neighborhood later in life, even when controlling for other variables such as the available schools, race, or ethnicity.

In part, that’s because family structure influences the choices that children will make: controlling for race and parental income, boys raised without their father are much more likely to use drugs, engage in violent or criminal behavior, go to jail, and drop out of school; girls, meanwhile, are more likely to engage in early sexual activity or have a child out of wedlock. Children without a father in the home are even more likely to suffer from mental health problems as adults.

Roy Baumeister and John Tierney’s book, Willpower, details a psychology test, where children can either receive a small prize right away, or receive a larger, more valuable prize 10 days later—if they forgo the smaller prize. En mass, children without a father in the home settled for the initial prize, while children with a father in the home were more willing to wait for the larger prize.

Research by David Autor and David Figlio studied and rejected the idea that these effects are mainly due to dangerous neighborhoods or poor schools. They concluded that “neighborhoods and schools are less important than the ‘direct effect of family structure itself.’”1

Family Breakdown is Class-Based

Family breakdown is extremely important if we care about a child’s social mobility—the average child does best with married parents, and, more specifically, with their biological father residing in their home.2 Yet America’s poor children have relatively few involved or present fathers.

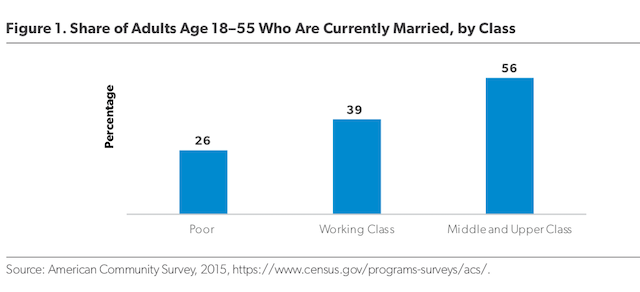

That’s because the vast majority of America’s overall marriage decline is concentrated among poor and working-class Americans, leading to a “marriage divide” based on class (see figure below).3

Source: Wilcox and Wang, The Marriage Divide, American Enterprise Institute, 2017.

As marriage rates fractured among America’s poor and working class, the institution has remained resilient among America’s better-off, who still marry at rates similar to those 50 years ago.

And the collapse of marriage among the working class has coincided with a sharp increase in out-of-wedlock births, often to cohabiting parents—because people see marriage as ideal but unattainable, yet still desire children.

Welfare May Have Played a Role

It is important to realize that things weren’t always so. The black American family provides a stark example. From 1890 to 1950, black women had a higher marriage rate than white women. And in 1950, just 9% of black children lived without their father. By 1960, the black marriage rate had declined but remained close to the white marriage rate. In other words, despite open racism and widespread poverty, strong black families used to be the norm.

But by the mid-1980s, black fatherlessness skyrocketed. Today, only 44% of black children have a father in the home. In unison, the rate of black out-of-wedlock births went from 24.5% in 1964 to 70.7% by 1994, roughly where it stands today.

One contributor to family breakdown, which soon spread to the poor and working-class white family, may have been welfare expansion. Cash welfare in meager form existed since 1935,4 and some welfare expansion took place during the Kennedy administration. But under Johnson’s Great Society, which began in 1964, benefits became substantially more generous and came under greater control of the federal government.

In the words of Harvard’s Paul Peterson, “some programs actively discouraged marriage,” because “welfare assistance went to mothers so long as no male was boarding in the household… Marriage to an employed male, even one earning the minimum wage, placed at risk a mother’s economic well-being.” Infamous “man in the house” rules meant that welfare workers would randomly appear in homes to check and see if the mother was accurately reporting her family-status.

The benefits available were extremely generous. According to Peterson, it was “estimated that in 1975 a household head would have to earn $20,000 a year to have more resources than what could be obtained from Great Society programs.” In today’s dollars, that’s over $90,000 per year in earnings.

That may be a reason why, in 1964, only 7% of American children were born out of wedlock, compared to 40% today. As Jason Riley has noted, “the government paid mothers to keep fathers out of the home—and paid them well.”

Identifying welfare as a contributor—along with shifts in the labor market and de-industrialization—explains why fatherlessness has spread as it has.5 For example, racial differences in marriage rates may be largely due to racial income disparities, which lead to stiffer marriage penalties for black adults.6 And today, many means-tested programs7 reach into the working class and lower-middle-class, which corresponds with a decline in marriage among these groups.8

In today’s America, four-in-10 families with children receive support from at least one means-tested transfer program.9 One study found that almost a third of Americans said they personally know someone who chose not to marry due to the fear of losing a benefit.

Time for Reform

State policymakers on both the left and the right who are concerned with declining social mobility and the state of our children should pursue compassionate reform. This includes reducing marriage penalties in welfare programs. A specific example of what state-led welfare reform could look like will be discussed in a subsequent article.

Willis L. Krumholz is a fellow at Defense Priorities. He holds a JD and MBA degree from the University of St. Thomas, is a CFA charter holder, and works in the financial services industry. You can follow him on Twitter @WillKrumholz.

1. According to Autor and Figlio, boys especially struggle without a father in the home. This is because, according to The Wall Street Journal’s William A. Galston, discussing Autor and Figlio’s research, “…boys’ problems are much more behavioral than cognitive. For example, truancy and classroom disciplinary issues lead to suspensions, which play the largest role in explaining the boy-girl high-school graduation gap. But the presence of fathers in the household substantially reduces the gaps between boys and girls in absences and suspensions. It turns out that boys need fathers as well as mothers even more than girls do, and suffer even more when fathers are absent from their lives.” William A. Galston, “The Poverty Cure: Get Married,” Wall Street Journal, October 27, 2015.

2. W. Bradford Wilcox, Chris Gersten, and Jerry Regier, The Effect of Marriage Penalties on Economic Mobility, Poverty, and Family Formation, (forthcoming, 2019).

3. Wilcox, Gersten, and Regier (forthcoming, 2019). Note on the figure: Poor families are those with incomes (not including benefits) below the federal poverty level (FPL), working-class families are those with incomes between approximately 100 percent and 200 percent of the FPL, and lower-middle-class families are those with incomes between approximately 200 percent and 300 percent of the FPL.

4. Aid to Families with Dependent Children (“AFDC”) was enacted in 1935, but controlled by the states (in the Jim Crow South, meager welfare programs were designed to be exclusionary and seasonal, at most acting as a subsidy to landowners who only wanted to pay agricultural laborers seasonal wages, but also wanted workers to stay in the South during the off-season, despite the lack of paying work).

5. Wilcox, Gersten, and Regier (forthcoming, 2019).

6. For the period 1988 to 1993, for example, Douglas Besharaov and Tim Sullivan found that “black single mothers are 50% more likely than white ones to face a marriage penalty that exceeds 10% of their income (46% versus 31%). See ”Douglas J. Besharov and Tim Sullivan, “Welfare Reform and Marriage,” The Public Interest (October 1996), pg. 7.

7. Such as the Affordable Care Act’s insurance subsidies, and childcare subsidies.

8. Wilcox, Gersten, and Regier, (forthcoming, 2019).

9. Id.