Highlights

- A new study of a pre-K program in Boston finds that the benefits are largely the preserve of affluent white boys. Post This

- The Boston study leaves unanswered questions about what would have happened to student outcomes if instead of launching a pre-K program, Boston had instead simply given families $20,000 per child. Post This

- When it comes to assessing the likely effect of a massive expansion of pre-K, the studies with the greatest external validity remain the Quebec Family Plan and the Tennessee Voluntary Pre-K Program. Both provide grounds for substantial alarm. Post This

Universal pre-K advocates have historically used studies the way a drunk man uses lampposts – for support rather than illumination, as the Brookings Institution’s Russ Whitehurst has pointed out. Their argument could be justly paraphrased: We have strong evidence that small, intensively resourced programs serving deeply disadvantaged students yielded strong benefits; therefore, we know that large-scale, less resourced, differently designed universal programs will also yield strong benefits.

But just as Congress is debating President Biden’s $1.8 trillion American Families Plan, with $425 billion going towards universal public pre-K as well as universally affordable child care, researchers have released a discussion draft of a paper demonstrating, as an author told the New York Times, “that modern large-scale public preschool programs can improve educational attainment.”

The study examines long-term outcomes for students chosen randomly by lottery to attend Boston’s public pre-K program (for four-year-olds) from 1997 to 2003. The top-line results are strikingly positive: participants were 6 percentage points more likely to graduate high school, and 5.4 percentage points more likely to enroll in college. They also received fewer suspensions in high school and were less likely to be incarcerated as a juvenile.

But underneath that topline, the findings get somewhat peculiar. In theory, public pre-k should provide a benefit either by allowing kids to enroll in a higher quality program than their families could afford, or by providing them with a more developmentally congenial environment than they would experience at home. Pre-K should, then, provide greater benefits for disadvantaged students from single-parent households. Much of the literature on childcare and pre-K conforms to this expectation.

But not this study. To put it somewhat crudely, but also probably more accurately than the authors put it themselves, this study finds that the benefits of pre-K are largely the preserve of affluent white boys.

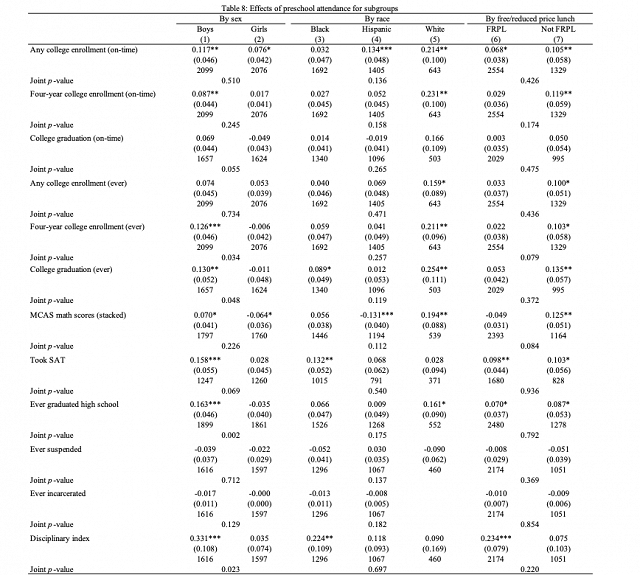

In their subgroup analysis by gender (see Table 8 in the study), the authors found no benefits for girls significant at a 5% or higher level. They found benefits for boys significant at a 5% or higher level for: taking the SAT test, high-school graduation, discipline, four-year-college enrollment, and college graduation. By race, white students saw significant improved outcomes on college enrollment, graduation, and standardized math test scores; black students saw improved outcomes only on discipline and SAT-taking; Hispanic students saw an increase in on-time college enrollment, but (oddly) a substantial deterioration in standardized math test scores. By poverty, higher-income students saw gains in college enrollment, college graduation, and standardized math test scores. Low-income students saw benefits only for discipline and SAT-taking.

Yet the authors claim in their public-facing brief that “there are no differences in preschool impact by race and income.” They make this claim because their joint P test shows that the differences by race and income can’t be stated with statistical significance. But the authors could have created an index (as they did with the discipline variable) or conducted a joint F test across all outcomes, which would likely have shown that the benefits were concentrated in advantaged and white students. The fact that they did not—and then presented a categorical public statement at apparent odds with their pattern of findings—is disconcerting. Though they claim otherwise, their findings appear theoretically incoherent, and theoretically incoherent findings are often a symptom of some other serious empirical problem.

But for the moment, let’s stipulate that this discussion draft is perfectly internally valid. In terms of external validity, it is surely an order of magnitude superior to the “go-to” studies typically touted by early education advocates (the High/Scope Perry Preschool Project and the Carolina Abecedarian Project). But it is still an extremely thin and tenuous reed on which to make the case for rapidly scaling universal pre-K for 3- and 4-year-olds with a massive infusion of federal cash.

The researchers claim that Boston’s pre-K program costs about $13,000 per child for a full-day, full-year program in today’s dollars. But that is a sloppy and incorrect cost calculation, based not on actual administrative expenses but rather on a third-party projection made two years prior to the launch, which assumed that middle-class parents would pay substantial fees to access public pre-K. Given that Boston pre-K teachers “are paid on the same scale as K-12 teachers [and] that pre-k teachers are required to get a masters’ degree within five years,” and that pre-K class size is similar to class size in the public school system, a more reasonable back-envelope calculation puts the cost of the program in line with overall per-pupil spending of about $20,000.

Furthermore, although Boston’s pre-K program was technically “universal” insofar as it was open to students regardless of income, it was still relatively small during the time period studied. At launch in 1997, Boston’s program served more than 2,500 students. In 1998, the school district cut the program back to under 1,000, where it remained for the duration of the period that was studied. Cutting back dramatically on the program may have enabled the school to select only the best teachers to remain in it, further undercutting the external validity of the study’s findings. While the program has grown since, the authors note that today—almost 25 years after—the pre-K program only has capacity to serve roughly half of Boston’s pre-K students.

When it comes to assessing the likely effect of a rapid and massive expansion of pre-K intended to yield a universal entitlement, the studies with the greatest external validity remain those conducted on the Quebec Family Plan and the Tennessee Voluntary Pre-K (VPK) Program. Both provide grounds for substantial alarm.

Quebec’s rapid and massive expansion of affordable child care/pre-K, which yielded a 14-percentage point increase in the share of 0-4 year-olds in center-based care, did substantial and lasting harm to children. Researchers found that time in child care was linked to increased hyperactivity, anxiety, and aggression, as well as deterioration in motor and social development. Research also found strong evidence of “worse parenting” after the new policy was put into place, as well as a significant deterioration in the reported quality of the relationship between the child’s parents. Based on all this, the researchers concluded that “the consistency of the results suggest that more access to child care is bad for these children (and, at least along some dimensions, for these parents).” Further studies provided the small silver lining that this damage was confined to students from two-parent households, and that child care still did some good for children from single-parent households. But the damage done was lasting. Researchers concluded that “the negative impact of the Quebec program on the noncognitive outcomes of young children appears to persist and grow as they reach school ages,” including a rise in anxiety and aggression as well as worse health and lower life satisfaction.

Tennessee’s statewide voluntary pre-K program serves about 18,000 low-income children at a high level of quality, according to the National Institute of Early Education Research’s metrics, but at a cost of less than $5,000 per student. The results were bad: by third grade, VPK students performed substantially worse on science and math tests, were more likely to be disciplined for behavioral infractions, and more likely to be diagnosed with disabilities.

The Boston Pre-K study provides evidence adequate to reasonably advise city mayors or school boards of well-resourced districts to experiment with the provision of small-scale pre-K programs. But as Congress considers dramatically expanding investment in early education, the Quebec Family Study and the Tennessee VPK study hold vastly more relevance to the American Families Plan, which would (as in Quebec) dramatically scale up early education provision and likely sustain it at a cost point closer to Tennessee’s $5k per pupil than Boston’s $20k. Hence we still, on balance, have more reason for alarm than optimism about what Biden’s American Families Plan will mean for children.

But for the sake of argument, let’s wave away the very real concerns about implementation. And let’s assume that the American Families Plan would yield two more grades in public schools funded at around $20k per year. And let’s assume that from this investment we could expect benefits similar to what researchers found in Boston. And let’s assume that these benefits would be universal, not reserved for affluent white boys.

It would still be far from clear that this study proves that universal pre-k would be a wise public investment. That’s because policymakers must necessarily deal in tradeoffs and counterfactuals, and this study leaves unanswered the question about what would have happened to student outcomes if instead of launching a pre-K program, Boston had instead simply given families $20,000 per child.

Max Eden is a Research Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.