Highlights

- Across all religious groups in America, men who attend religious services more frequently are far less likely to view pornography. Post This

- Today, Protestant men who attend church regularly are basically the only men in America still resisting the cultural norm of regularized pornography use. Post This

- Guess who are the happiest husbands? Religious men who do not use porn. Post This

Is misplaced guilt arising from sexual prudishness destroying Christian relationships? In a recent interview in The New Yorker, sociologist of religion, Samuel Perry said:

What I found is that, whatever we think pornography is doing, those effects tend to be amplified when we’re talking about conservative Protestants. It seems to be uniquely harmful to conservative Protestants’ mental health, their sense of self, their own identities—certainly their intimate relationships—in ways that don’t tend to be as harmful for people who don’t have that kind of moral problem with it.

The effects of pornography aren’t just about watching images on a computer screen but what that activity means to your community. It’s what that activity means to you. And so, with conservative Protestants, you have this fascinating paradox of a group of people who hate pornography morally. They want to eradicate it from the world. And yet, statistically, they will view it slightly less often than your average American. And so you have this paradoxical situation of a group of people who collectively hate it, and yet, as individuals, they semi-regularly watch it. Especially the men. What are the consequences of that kind of incongruence in their lives?

The public reviews and discussions of Dr. Perry’s new book, Addicted to Lust: Pornography in the Lives of Conservative Protestants, could leave you thinking that conservative Protestant relationships are being ruined by a scourge of misplaced shame over pornography use. But the book itself is far more sedate in its claims. Perry uses extensive qualitative and quantitative data from numerous sources, including extensive interviews he conducted with conservative Protestant pastors and believers, to argue that pornography has been uniquely damaging to the relationships of conservative Protestants. Given the topic, the book has received an enormous amount of media attention that generally leaves the impression that the moral scruples of conservative Protestants are ruining their marriages.

Perry’s argument is that among our secular neighbors, the husband (or wife) watching pornography doesn’t tend to lead to great unhappiness or divorce very often; but among conservative Protestants, relationship troubles arising from pornography are far more frequent. Perry is a thoughtful researcher and writer, and so he doesn’t think Christians just need to abandon their sexual mores, but he does suggest that Christians need to be more open to talking about the issue and removing the shame associated with pornography.

Protestant Men Use Porn Less

It's an interesting take. But the claims of the book turn out to be far less sensational than the title would suggest and, ultimately, may serve as an encouragement to conservative Protestants.

For example, Perry uses data from the General Social Survey (GSS) to show that, among Protestant males who are members of the most conservative denominations, the share who have viewed a pornographic film in the last year has been roughly stable for the last 20 years, at around one-third. This is a far less dire picture than many religious leaders paint. He goes on to argue that, since porn use is actually stable, the rapidly-growing level of concern among religious leaders about pornography use is perhaps misplaced. While he doesn’t call this a “moral panic,” the concept seems to be lurking in the background of his reasoning.

I think Perry misreads the evidence. He focuses on denominational identity and beliefs, and so suggests that conservative Protestants view slightly less pornography than other Americans. But when I cut the data by religious identity and religious attendance (that is, actual religious behaviors that signal costly commitments to faith and who actually participates in church life) the difference becomes stark.

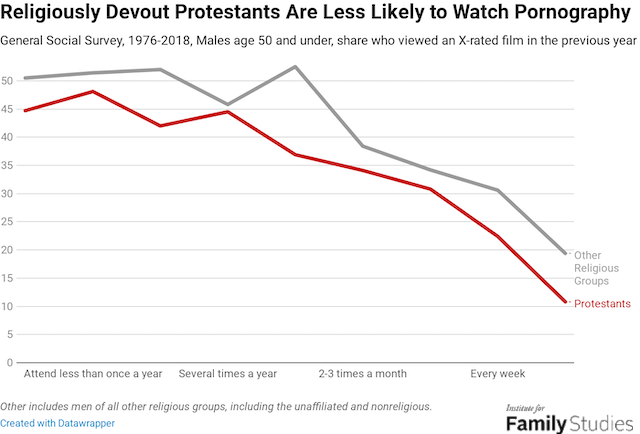

Across all religious groups in America, people who attend religious services more frequently are far less likely to view pornography. Nominally-Protestant men are nearly five times more likely to view pornographic films as men who frequently attend religious services (more than weekly). And across all levels of religious attendance, Protestant men are about 5 to 10 percentage points less likely to have viewed porn in the last year.

These are meaningful differences! They suggest that religiously-observant Protestants are experiencing a vastly lower rate of pornography use. That isn’t the impression you would get from Addicted to Lust, which leaves the impression that the devout use pornography just a bit less than the rest, when, in fact, the gap is enormous.

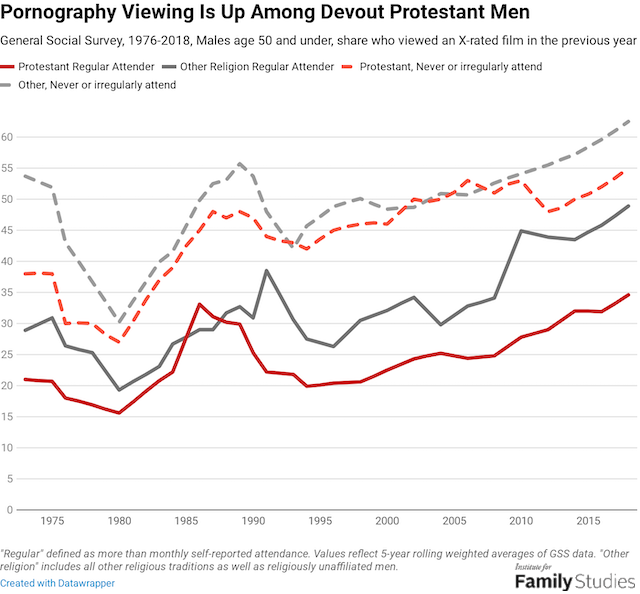

Even so, it is important to note that pornography use is rising among these men.

The share of Protestant men who report having watched a pornographic film in the last year has risen to about a third even among those who regularly attend church.

But Protestants are becoming more distinctive over time. Through the 1980s, Protestants and other regular church-goers looked similar. But over time, non-Protestant churchgoers have developed porn habits very similar to their less devout neighbors. Today, Protestant men who attend church regularly are basically the only men in America still resisting the cultural norm of regularized pornography use.

Thus, pornography use is much lower among devout Protestants than other people, suggesting Protestant belief and behavior truly is distinctive. However, because pornography use is rising among Protestant churchgoers, it makes sense for Protestant pastors to perceive pornography as a growing issue. This, again, contradicts Perry’s argument that the growing Protestant concern for pornography use is detached from any actual growing problem. While porn use remains comparatively low among devout Protestant men, it is rising.

Is Porn the Only Problem?

But Perry’s main argument boils down to a suggestion that pornography has only very modest negative effects on most peoples’ relationships—that porn is far more damaging if the people in that relationship are typical conservative Protestants. That is, it is our hang-ups as Christians about porn that destroy our relational happiness—not the porn itself. Hold on to that thought.

A recent New York Times article chronicled how progressive men are failing to shoulder an egalitarian burden of parenting. That is, these men say they believe in egalitarianism, but then don’t enact it. As a result, their marriages face extra anger and unhappiness, especially for their wives.

Would it be proper to say that the cause of the unhappiness here is the expectation of egalitarianism? No. Clearly, the problem is that the progressive dad doesn’t live up to the standard he professes.

Adherence to the sexual norms promoted by conservative Protestants—delaying sex until marriage and monogamy within marriage, including (for most) avoiding porn—is consistently associated with greater marital happiness.

The same holds for conservative Protestants: it’s absurd to suggest that the problem is the expectation of sexual exclusiveness. All people, all couples, have a variety of expectations that they imperfectly achieve. The fact that conservative Protestants hold a particularly sacred view of human sexuality makes them idiosyncratic on the question of porn, but there is nothing unusual about having idiosyncracies.

What Perry has explained in book-length is that when couples have big disagreements about things they care about, it tends to make them unhappy. While there are better and worse ways to handle disagreements, at the end of the day, if a couple shares the conviction that pornography use is wrong, but one partner keeps using pornography, no amount of speaking in a calm voice resolves the issue. Actions have consequences, and the failure to live up to our own moral standards, and those of the people we love, ought to create psychological discomfort, even distress. There’s no get-out-of-jail-free card for the consequences of relational sabotage. A life free of this kind of psychological discomfort is simply a life of narcissism—where no moral code is regarded as ever having a claim superior to one’s immediate desires.

In other words, Perry is almost certainly correct that when couples regard pornography as immoral and one member of the couple violates that standard, it makes both partners unhappy. But while conservative Protestants may be unique for strictly opposing pornography, virtually all people have some kind of standard to which they hold their spouse, and most of us can recall the litany of times we failed to live up to our spouse’s standards, or vice versa. More to the point, while high standards create more opportunities for failure, it turns out that strict moral standards for a relationship, be they traditional-religious or egalitarian, are associated with greater relationship satisfaction, not less!

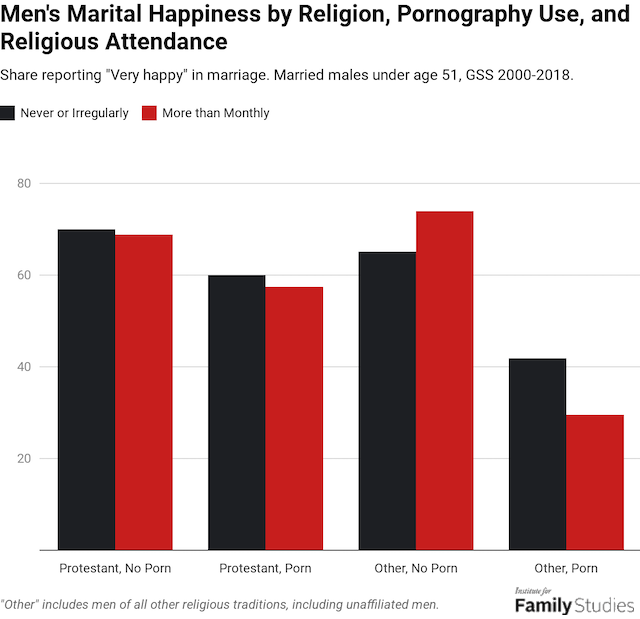

And indeed, data from the GSS shows that even accounting for pornography, married Protestant males are pretty happy. Those who abstain from porn are as happy or happier than married men of other faiths who abstain from porn, while married Protestant males who have viewed pornography in the last year are far happier with their marriages than men of other faiths who did so.

Obviously, correlation isn’t causation—unhappiness could cause porn use rather than the other way around! But at a very basic level, it appears that most married Protestant males are pretty happy, regardless of whether or not they view pornography.

Conservative Protestants Tend to be More Sexually Satisfied

But on a larger scale, Perry’s book could lead you to believe that conservative Protestants have miserable sex lives. That isn’t his argument, but popular portrayals of the issue can come close to that.

The reality, however, is that religious people are among the most sexually satisfied. Adherence to the sexual norms promoted by conservative Protestants, that is, delaying sex until marriage and monogamy within marriage, including (for most) avoiding porn, is consistently associated with greater marital happiness. While it is undoubtedly true that disagreement with culturally normative pornography use creates psychological stressors for conservative Protestants, on the whole, conservative Protestant sexual norms are highly conducive to individual and marital happiness. Our issues with porn are not severe enough to offset the fact that our lifestyle model of chastity until marriage and commitment within marriage is, in fact, the most strongly happiness-associated lifestyle in America today.

Perry spends a lot of time discussing various religious ideas within Protestantism. But there’s one more religious concept he could have benefitted from discussing.

Conservative Protestants would simply assert that the psychological distress Perry observes is what the 19th-century Lutheran writer Soren Kierkegaard called, “the sickness unto death,” or, more simply, “despair over sin.” Most conservative Protestants subscribe to the belief that religious faith requires a recognition of one’s own sinfulness. Faced with that despair-inducing recognition, some seek resolution through faith: they confess, repent, and receive absolution from God and their community. But some people, faced with this encounter, have a different reaction: they cling to the behavior that conservative Protestants would describe as “sin.” In time, so the theological explanation goes, clinging to this behavior corrodes faith and that person may eventually leave that faith.

This theological model has been adopted by Christians for approximately 2,000 years. And Perry finds it in the sociological data on pornography, saying his interview with The New Yorker:

After looking at pornography for a long enough time, [some conservative Protestant men] started to back away from their faith a little bit. They were less likely to pray, less likely to attend church, less likely to feel like God is playing an important part in their lives.

And I think that is how we respond to cognitive dissonance. The classic theory is that, if we find ourselves engaging in behavior that we believe violates our values, we can do one of two things: we can stop the behavior or change our values. And oftentimes, when conservative Christians keep on struggling with this temptation in their lives, it’s just easier for them to say, “You know what? Maybe I don’t believe this so much. Maybe I could just keep doing this and not think the religious part of it is so important.”

Porn Is a Real Problem: But Conservative Protestants Are Doing Okay

Perry’s book contains thoughtful, novel research that contributes valuable information on an important question: struggles with pornography are indeed harming the relationships of many people and seem to be especially painful for conservative Protestants.

But this finding should be attached to caveats: other cultural groups have their own idiosyncratic hang-ups, and there’s no evidence that conservative Protestants have a uniquely severe or intense problem compared to other potential relational problems. Furthermore, whatever effect pornography is having, it isn’t enough to offset the effects of many other lifestyle choices conservative Protestants make that are strongly associated with personal, marital, and sexual happiness. In the end, the sociological phenomena Perry observes related to pornography are a neat demonstration that ancient Christian moral reasoning continues to serve as a decent working theory of how human societies, and human consciences, actually function.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, and an Adjunct Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.