Highlights

- Closely-connected extended families are far more effective in transmitting cultural and religious values across generations. Post This

- There is no more powerful explanation for why Americans leave religion, or why they never take it up in the first place, than the family. Post This

- Americans raised in blended families, interfaith families, or single-parent families are far less likely to have participated in religion growing up. Post This

More than a decade ago, the Pew Research Center released a path-breaking study on people without religion: “Nones” on the Rise. At the time, I was in graduate school studying political science and working full time as a pollster. Partly inspired by this work, I wrote my dissertation exploring why people leave religion: “And Then There Were Nones: An Examination of the Rising Rate of Religious Non-affiliation Among Millennials.” (I’m a fan of Agatha Christie). I never turned it into a book, despite some prodding, but I remain passionately engaged in the topic.

So when I came across Jake Meador’s recent article in the Atlantic, “The Misunderstood Reason Millions of Americans Stopped Going to Church,” I dropped everything to read it. Meador wonders whether American culture has become too hyper-individualistic for religious communities to thrive. He states:

Contemporary America simply isn’t set up to promote mutuality, care, or common life. Rather, it is designed to maximize individual accomplishment as defined by professional and financial success. Such a system leaves precious little time or energy for forms of community that don’t contribute to one’s own professional life or, as one ages, the professional prospects of one’s children. Workism reigns in America, and because of it, community in America, religious community included, is a math problem that doesn’t add up.

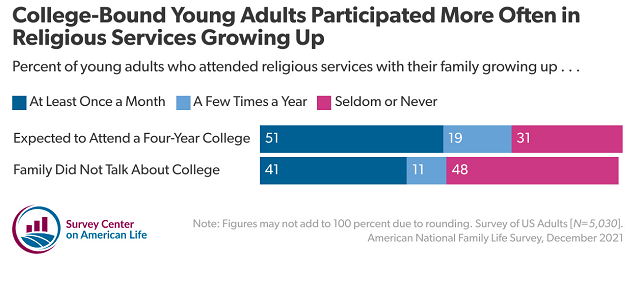

It's an intriguing idea. But it doesn't quite fit the data. Young people who were raised by parents who expected them to go to a four-year college were far more active in religion during their formative years than those without those same expectations. More than half (70%) of college-bound young people said they went to religious services with their family at least a few times a year during their childhood. In contrast, young people whose parents never discussed the option of college were far less active—nearly half (48%) said they seldom or never attended services.

The college divide in religious participation runs in the opposite direction this argument would suggest—college-educated Americans tend to be more involved in religion than those with fewer years of formal education.

An obsessive focus on enrichment activities and tightly-controlled schedules has become a central feature of many middle-class and upper-middle-class parenting strategies. I’ve argued that this type of parenting approach contributes to loneliness and heightened anxiety among young people. Johnathan Haidt argues much the same in a recent Substack post:

With every decade children have become less free to play, roam, and explore alone or with other children away from adults, less free to occupy public spaces without an adult guard, and less free to have a part-time job where they can demonstrate their capacity for responsible self-control.

There are many reasons to be concerned about this development, but it's ill-suited to explain America’s cross-cultural religious decline. There’s simply not much evidence that hyper-involved parents are taking kids out of Bible study to enroll them in Russian math classes.

The question remains: what is the reason so many young people are leaving religion? There’s no single answer, but the most compelling explanation is that changes in American family life precipitated this national decline. American families have changed dramatically over the past few decades and many churches have been slow to respond. Americans raised in blended families, interfaith families, or single-parent families are far less likely to have participated in religion growing up. And these types of family arrangements have become far more common today than they once were. The family explanation is compelling for a few reasons:

- Young people today are leaving much earlier than those of previous generations. Seventy percent of young adults who have disaffiliated shed their formative religious identities during their teen years.

- The Americans most likely to “leave” religion are those with the weakest formative attachments. Compared to previous generations, Generation Z reports having a less robust religious experience during their childhood.

- Most Americans who disaffiliate say they “drifted away” from religion rather than experiencing a singular negative or traumatic event that pushed them out. To put it another way, they quiet quit.

- A wealth of research has shown that religious socialization in the family is a key component of the transmission of religious values, identity, and beliefs across generations.

Back in 2020, David Brooks wrote about the disintegration of traditional family life that featured large, interconnected networks of extended family members—grandparents, in-laws, cousins, nieces, and nephews. Brooks argues that extended families, composed of a flexible web of relationships, provide greater stability, and security for all family members. He wrote: “If a mother dies, siblings, uncles, aunts, and grandparents are there to step in. If a relationship between a father and a child ruptures, others can fill the breach. Extended families have more people to share the unexpected burdens—when a kid gets sick in the middle of the day or when an adult unexpectedly loses a job.” I would argue that closely-connected extended families are far more effective in transmitting cultural and religious values across generations as well.

The rise of nontraditional family arrangements is hardly the only factor responsible for the decline of American religion. Politics are an important factor, and growing religious diversity likely plays a role as well. Americans are far more likely to have nonreligious friends and family members today, and this is especially true of young adults. There’s growing evidence that religious diversity undermines commitment. My own research has shown that geographically, the places where religion has endured tend to be the most homogeneous. There are multiple pieces of this puzzle. I’ve written as much. But if you push me on this, I think there is no more powerful explanation for why Americans leave religion, or why they never take it up in the first place, than the family.

Daniel A. Cox is the director and founder of the Survey Center on American Life and a senior fellow in polling and public opinion at the American Enterprise Institute.

Editor's Note: This essay was first published in the author's newsletter, American Storylines. It has been republished here with permission.