Highlights

- While pro-natal policy isn’t a sure-fire political winner, it hasn’t yet been politically polarized. Post This

- Across various demographic groups, the leading reason respondents give for not having children yet is “I’m single.” Post This

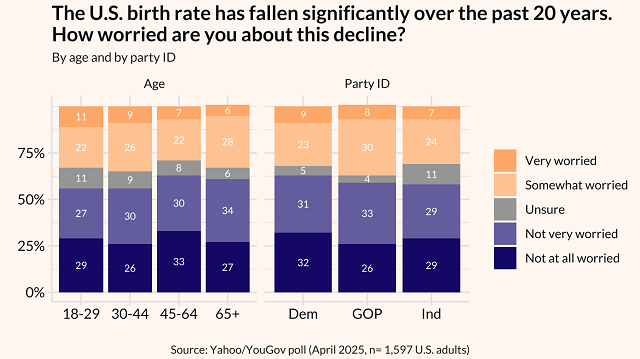

- The long-term consequences of falling birth rates have yet to fully permeate the public consciousness. Less than 1 in 10 Americans are “very” worried about declining fertility. Post This

For the better part of this century, the nascent movement to make it easier for people to start families and have children flew largely under the popular radar. A few Cassandras tried to warn us, like AEI’s Nick Eberstadt, or Jonathan V. Last, author of What to Expect When No One’s Expecting. But concerns about falling birthrates were ignored or treated as crankish, as opposed to the respectful treatment given to neo-Malthusian “Population Bomb” propaganda that warned of over-population.

The ship is slowly starting to turn, as nearly every country across the globe records ever-lower birth rates. Before he was Vice-President of the United States, J.D. Vance was telling audiences that “We want babies not just because they are economically useful. We want more babies because children are good. The world’s richest man advancing his idiosyncratic understanding of “pro-natalism” might claim some of the credit, too. As the New York Times’ Caroline Kitchener reported, many pro-family and pro-natalist voices have approached the White House proposing all manner of efforts aimed at boosting birth rates.

But what do the American people think of these natalist energies? Would an unabashed embrace of policies explicitly aimed at inducing fertility be welcomed, opposed, or ignored? Much depends on the policy, the design, and the messenger. And a new survey from Yahoo and YouGov gives us some of the best looks at the popularity of some of the ideas covered in the Times’ reporting.

To start, it appears that the long-term consequences of falling birth rates have yet to fully permeate the public consciousness. Across the board, less than 1 in 10 Americans proclaim themselves “very” worried about declining fertility. About one-quarter of adults say they are “somewhat” worried about falling fertility, with the majority of Americans not finding much to be concerned about. (In 2022, a different YouGov poll found that Americans were more than twice as likely to believe overpopulation would be a bigger problem than underpopulation.) And political differences on the question are scarce; only 8% of self-identified Republican voters are "very worried" about declining birth rates, though more Republicans than Democrats declared themselves “somewhat” concerned.

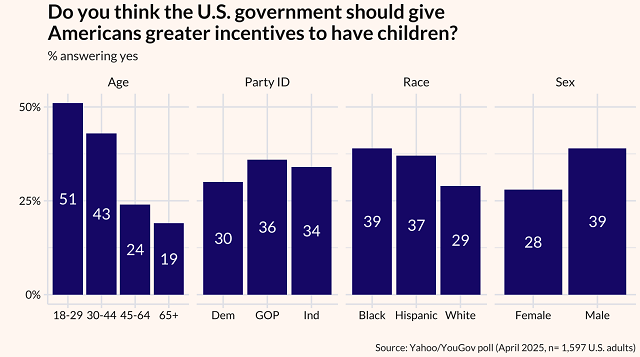

Perhaps this sanguine attitude helps explain the fact that avowedly pro-natalist policies, such as those pitched in the Times piece, aren’t runaway winners. When asked if the “U.S. government should give Americans greater incentives to have children?,” only one-third of Americans say there should be more incentives for would-be parents, with men (39%) being more likely than women (28%) to support the idea. Racial minorities also supported the idea more than whites.

But there are real differences among some demographic subgroups. Perhaps unsurprisingly, young people—who by definition stand to gain the most from any transfer scheme that prioritizes the fertile over those who can no longer have children—are most likely to support government action to boost birth rates. Gen X and older are decidedly cool on the question. And while voters who identify as Republican are a little more likely to support the idea in theory, Democrats and independents aren’t far behind; suggesting that while pro-natal policy isn’t a sure-fire political winner, it hasn’t yet been politically polarized.

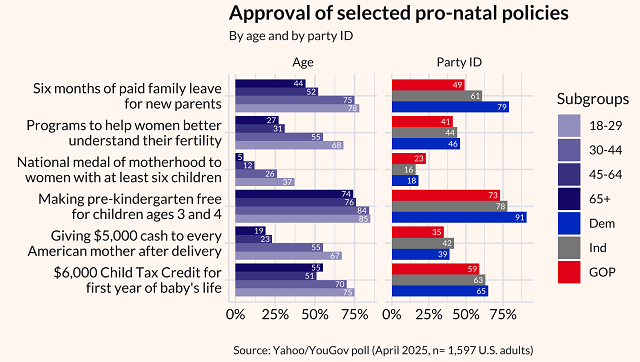

The survey then asks respondents whether they “approve” or “disapprove” of a suite of six policies that have been discussed in pro-natalist circles: free pre-kindergarten for 3- and 4-year-olds, paid family leave, programs to help women better understand their cycle and fertility, a national medal given to mothers with six or more children, a $5,000 “baby bonus”, and expanding the Child Tax Credit to $6,000 for the first year of a baby's life (which was proposed in 2024 by Kamala Harris' campaign.)

As with any public opinion poll, the limited wording on the question shouldn’t be taken as the final word on any given policy design (for instance, whether a Child Tax Credit should have a boost for married couples or a work requirement. And the “approve/disapprove” structure means voters are answering a different question of whether they think such a plan would work to boost fertility or family formation or not).

For instance, the best-performing policy idea, making pre-kindergarten free for children age 3 or 4, racked up supermajority support, with 79% of respondents saying they “approve” of the policy. But it could very well be that these respondents are supporting pre-K not on pro-natal grounds, or even on child development grounds, but because they see it as a way of helping parents get back to work.

And we can see that, in general, Democrats are slightly more likely to favor spending money on supporting parents and their children than Republicans (though in most cases, not more than the presumed margin of error.) Younger respondents are much more likely to support paid leave, a baby bonus, or efforts to help women to better understand their fertility than older ones. Framing matters: the budgetary cost of six months of paid leave could well surpass the $5,000 baby bonus, yet it has stronger support, likely because of its association with enhancing workforce attachment. And, unsurprisingly for a country without much of a history of civilian honors, the idea of a “national motherhood medal” does not seem to resonate with many.

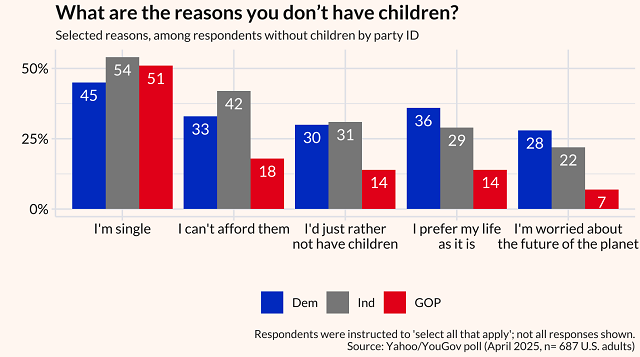

Beyond public opinion towards fertility policies, the Yahoo survey also asked respondents without children why they hadn’t become parents yet. Two things jump out. First, the leading reason respondents give for not having children yet, across various demographic groups, is “I’m single.” If not for that, about one-third of respondents guessed that they’d have had children by now. Secondly, while the overall rates of childlessness didn’t differ, Democratic adults without children are much more likely to relate politically-relevant reasons for why they are childless, like climate change and career concerns, compared to Republicans.

As the parties realign along educational lines, college-educated adults are more likely to identify as Democrats. So it’s not surprising that legacy media – which skews both progressive and college-educated – tends to focus on aspects of childlessness that fit into a left-leaning framework, like a “burning planet,” the “unsustainability” of modern-day parenthood, or the expectations that children are unattainable expenses. But that doesn’t fit the experience of all childless Americans.

Moreover, these findings underscore how any article, book, or panel discussion about declining birth rates must always come back to addressing the fundamental truth that declining fertility is downstream from our societal decline in relationship formation and marriage.

It remains to be seen whether the White House will champion any of these policies that have been proposed, or whether their pro-family efforts will look different. But they would be wise to take key findings from the Yahoo poll: That Americans aren’t yet convinced that low birth rates are a crisis, and that pro-natal policies probably aren’t a political winner—yet. But these issues do poll best among young adults.

As this survey suggests, pro-natal policies may be received best if they are seen as supporting parents rather than trying to induce people to have children. This survey is just the latest to hint that Americans need to be educated about the social and economic consequences of a low fertility future, and that some pro-family policies have the ability to capture some eyeballs—and maybe even sway some votes. A high-profile White House Summit on the Future of the Family, as I have previously proposed, could help raise real awareness of the scale of our birthrate trajectory, and might even pay political dividends by focusing attention on substantive (that is, non-gimmicky) policy proposals to better support parents.

Patrick T. Brown (@PTBwrites) is a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, where he writes the weekly “Family Matters” newsletter.