Highlights

Numerous developments over the past few years have drawn attention to the plight of small-town America. The opioid epidemic, though well in progress, burst onto the national radar about half a decade ago. Studies have documented that freer trade with China left behind many places that relied on manufacturing employment. And, of course, there was the election of Donald Trump.

The question of what to do with struggling localities has produced a lot of suggestions, but a recurring one is that people should simply leave places where there's no work. On the wonkier side of things, Eli Lehrer and Lori Sanders once proposed allowing people who lose their jobs to cash out their future unemployment benefits to fund a move. And on the more rhetorical side, two of my National Review colleagues had an interesting spat a few years back: Michael Brendan Dougherty, then working for The Week, asked what conservatives had to offer to someone struggling in Garbutt, New York. Kevin D. Williamson replied: "Get the h*** out."

But where does one go from Garbutt?

It used to be the case that low-skilled rural workers could earn a lot more if they moved to a big city. But that advantage has declined over the years. And as the cities have filled up and resisted becoming even denser, housing costs have skyrocketed. A new study from Philip Hoxie of the American Enterprise Institute and two coauthors puts these two together—less of a wage premium, higher rents and mortgages—and finds that workers who never went to college actually earn less in denser areas after the cost of housing is subtracted.

This study joins a growing and troubling line of research suggesting that highly productive big cities, through policy choices that limit density and drive up housing costs, are making it harder for the poor and sometimes even the middle class to move in and better themselves. This is not an excuse for staying somewhere where work has dried up, as I'll explain in a bit, but it's certainly a reason to stay out of San Francisco.

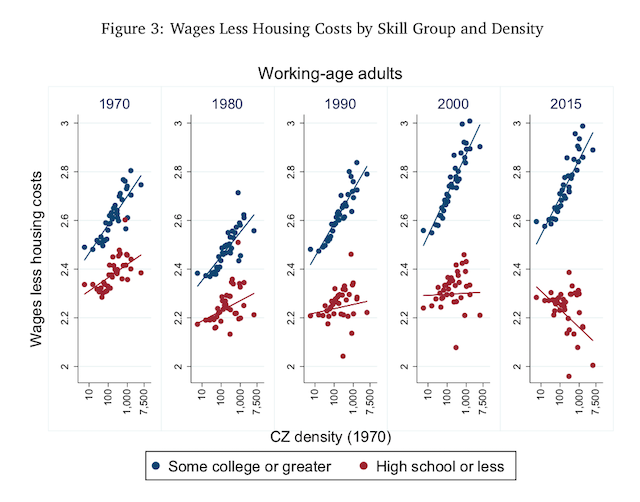

Hoxie et al. look at Census Bureau data on working 16-64-year-olds from 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000, and the 2011-15 period. They separate workers with at least some college from those with none, calculate the workers’ earnings in each of 722 "commuting zones," subtract the cost of housing, and rank the zones based on how dense they were in 1970.

Here's the key chart from the report based on those breakdowns. It implies that the benefit of moving to a denser area has steadily eroded for lower-skilled workers, and indeed recently turned outright negative. In other words, moving to a denser area actually costs money for those who don't have the education needed to get a high-paying job.

Now, one might nitpick the methods a few ways. In an analysis where the college/non-college distinction is so crucial, I would probably focus on the "prime working age" group of 25-54 rather than including people as young as 16. And there are some ways in which applying that distinction across such a large time period forces one to compare apples with oranges.

According to my own analysis of the Census data, among those who were 16-64 and employed, noncollege workers were the least educated 73% of all workers in 1970 but only the least educated 41% in 2011-15; immigration has also driven substantial demographic shifts in the past half-century, and women’s labor-force participation has risen considerably. Finally, looking within years, the analysis doesn’t control for demographic differences across cities that might cause differences in earnings regardless of density (such as the share of “non-college” workers who lack even a high-school degree, and the precise credentials earned—or not—by workers who attended college), or for differences in the level of social services provided to the working poor, which might offset housing costs.

But whatever marginal differences one might make by tweaking these details, that's one scary chart, and it sends a strong message both to policymakers and individuals thinking about moving.

On the policy front, this is just one study in a long line of such studies pointing out that the nation's biggest, most productive, and most economically vibrant areas have shut out lower-skill and sometimes even middle-class workers through various regulations, from density restrictions in urban cores to single-family zoning in the suburbs.

To take just two of the most recent studies, one last year found that housing constraints “lowered aggregate US growth by 36 percent from 1964 to 2009,” and one in 2017 blamed those constraints, in part, for the fact that incomes in different regions are converging less quickly than they used to. These places could grow in size, collect more taxes, provide more opportunities to those born elsewhere, and become even more fearsome economic powerhouses just by letting folks respond to a market demand for more housing. That's basically the fabled $20 bill lying on the sidewalk that no one bothered to pick up yet, though, of course, there are plenty of special interests lined up against making cities and their suburbs even denser than they already are.

But what about the individual level? Certainly, this study shows that low-skilled Americans looking for new opportunities shouldn't seek out density, per se. And it clearly shows they can be frustrated by the lack of opportunity in the biggest cities. Yet the study doesn't quite answer the Garbutt question posed earlier. Maybe someone leaving a downtrodden town shouldn't head to New York or Los Angeles, but that doesn't mean they should stay put.1

Take another gander up at that chart from the study, and remember I said there were 722 commuting zones in the analysis. Each dot obviously doesn't represent a single commuting zone; instead, numerous zones are "binned" together,2 which makes the plot more readable but also obscures the immense differences among places in the U.S.—even places that have the same density.

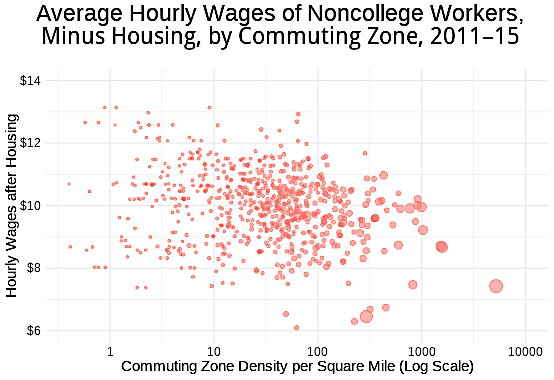

I obtained the underlying data from the authors and used it to make the following chart, which depicts the after-housing hourly wages of non-college workers in the 2011-15 period. Each dot here represents a single zone, with the sizes representing the places' working-age populations (which, like density, the authors measured as of 1970). For simplicity, I present wages after housing in simple dollar amounts rather than logarithms.

Note: Author's analysis of data provided by Philip Hoxie.

For a person living somewhere at the bottom, there are definitely lots of better places to head. At the extremes, one might find somewhere in which non-college jobs pay 50% more, taking housing into account. (Though remember, that not all "non-college" workers have exactly the same education and other traits, and these data aren't adjusted to account for such differences.) In other words, don't move to density; move to somewhere that similar people thrive, with their earnings covering their dwellings with some money to spare.

As Americans, we do need to ask ourselves how to balance the role of government and the role of personal initiative. But in this case, there's plenty of room for both.

Robert VerBruggen is an Institute for Family Studies research fellow and a policy writer for National Review Online.

1. If you're curious about Garbutt in particular, in this study it's part of a larger commuting zone that includes Rochester, and where wages after housing for non-college workers amount to roughly $10 an hour. This is pretty typical, so maybe Garbutt isn't so bad if you're willing to commute somewhere nearby for work. I’ve never been there, myself.

2. This is a common but somewhat controversial practice.