Highlights

In 1997, when Quebec, Canada, launched full-day, year-round child care for all children under age 5, the title of its policy brief read, “Children at the heart of our choice.” The assumption, of course, was that government-subsidized, universal day care would provide all children the potential for a “healthy start” in life, while simultaneously enabling many more women to enter the workforce and increase their earning potential.

Within 10 years, comprehensive analyses of the universal, “$5 per day childcare” program, including its impact on child care use, employment patterns, and children’s and parent outcomes, suggested cause for concern. Social development among children, as indicated by both emotional and behavioral measures, had significantly deteriorated in Quebec, relative to the rest of Canada (10% of a standard deviation lower). Comparisons between children ages 2 to 4 who had been exposed to the program, with older children (and siblings) who had not, revealed significant increases in anxiety, hyperactivity, and aggression in those exposed to the program. And the analyses found more hostile, inconsistent parenting, and lower-quality parental relationships among parents of children exposed to the program. But it was hard to predict whether the negative outcomes identified for 2- to 4-year-olds would persist across their development, or simply dissipate.

For decades, early intervention programs for children from high-risk environments, such as Head Start, the Perry Preschool Project, and the Abecedarian Project, had explored whether intensive positive intervention in a child’s early years actually carried through to adulthood by improving economic outcomes and lowering incidence of criminal behavior. Evidence suggested that some of these positive effects did persist in adulthood. But would the same be true of negative outcomes associated with exposure to programs in early childhood?

Twenty years after the Quebec program’s implementation, a second set of comprehensive analyses were conducted by Michael Baker, Jonathan Gruber, and Kevin Milligan (forthcoming, in the American Economic Journal). After replicating the previous results for children ages 0 to 4, the authors explored whether the negative outcomes associated with exposure to Quebec’s early, extensive day care program persisted into ages 5 to 9, the pre-teen years, adolescence, and young adulthood.

Their research confirmed that the negative effects did continue, and in some cases became stronger across development. Among 5 to 9-year-olds, negative social-emotional outcomes not only persisted, but in some cases increased, as indicated by 24% of a standard deviation increase in anxiety, a 19% increase in aggression, and a 13% in hyperactivity. The impact on boys and children with the most elevated behavioral problems was stronger, especially in measures of hyperactivity and aggression.

Using a specific type of regression analyses based on what is called “The Recentered Influence Function” (RIF), Baker, Gruber, and Milligan found that the “primary impact” of the Quebec program was to increase behavioral problems especially “for those who already had high scores.”

Source: M. Baker, J. Gruber, & K. Milligan, "The Long-Run Impacts of a Universal Child Care Program," 11/8/18

Copyright American Economic Association; reproduced with permission of the American Economic Journal: Economic Policy.

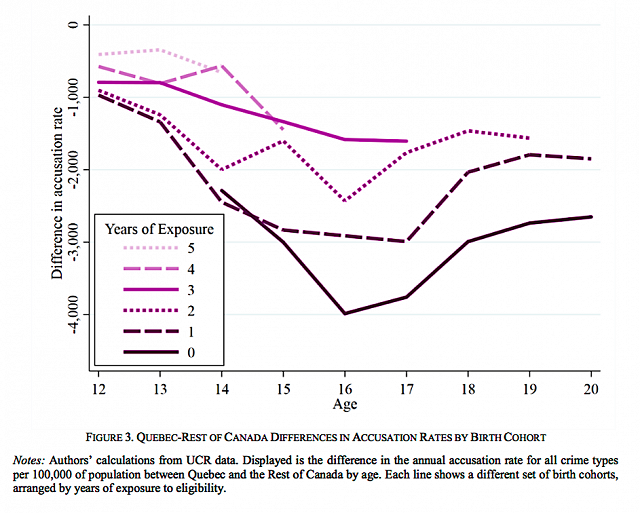

For youth and young adults, ages 12 to 20, analyses of self-reported general health and life satisfaction indicated that negative social-emotional outcomes associated with exposure to the daycare program persisted into young adulthood. The most striking finding was a “sharp and contemporaneous increase in criminal behavior” for those exposed to the universal day care program compared to their peers in other provinces. Though crime rates in Quebec are lower than the rest of Canada, there was a significant increase in crime accusation and conviction rates for those cohorts exposed to the Quebec child care program. There was an increase of 19% in the average rate of criminal accusations and an increase of 22% in the average rate of criminal convictions. As with the 5- to 9-year-old measures, the impact on criminal behavior was greater for boys, and for those who already had elevated behavioral problems.

Source: M. Baker, J. Gruber, & K. Milligan, "The Long-Run Impacts of a Universal Child Care Program," 11/8/18

Copyright American Economic Association; reproduced with permission of the American Economic Journal: Economic Policy

Baker, Gruber, and Milligan acknowledge that there is some evidence of positive impacts from universal child care programs in certain nations for children of certain ages. But in most cases, the benefits are primarily for less-advantaged children. As they conclude, “There is little clear evidence that these programs provide significant benefits more broadly.”

The timing and extent of the Quebec child care program provided the unique opportunity to comprehensively evaluate the implications of a universal day care program on many children from childhood to young adulthood. Importantly, the findings from the Quebec program are largely consistent with findings from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s comprehensive evaluation of day care in the United States. That study, which followed the same 1,364 children every year from birth, found that extensive hours in day care early in life predicted negative behavioral outcomes throughout development, including in the final assessments done when the children were 15 years old.

By age four-and-a-half, extensive hours in day care predicted negative social outcomes in every area including social competence, externalizing problems, and adult-child conflict, generally at a rate three times higher than other children. In caregiver reports of behavioral problems, only 2% of children who averaged less than 10 hours per week of day care during the first four years of life had at-risk scores, while as much as 18% of children who averaged more than 30 hours per week did. Family economic status, maternal education, quality of child care, and caregiver closeness did not moderate these effects. But would those effects persist?

By third grade, children who had experienced more hours of non-maternal care were rated by teachers as having fewer social skills and poorer work habits. More time in day care centers specifically predicted more externalizing behaviors and teacher conflict, too. Hours spent in day care centers specifically continued to predict problem behaviors into sixth grade. But by age 15, extensive hours before age four-an-a-half in any type of “nonrelative” care predicted problem behaviors, including risk-taking behaviors such as alcohol, tobacco, and drug use, stealing or harming property, as well as impulsivity in participating in unsafe activities, even after controlling for day care quality, socioeconomic background, and parenting quality. And much like the findings for the Quebec childcare program, the statistical effects linking day care hours with problem behaviors at age four-and-a-half were nearly the same as the statistical effects at age 15.

As with the persistence of negative effects across development, there is also evidence for the persistence of positive effects when children are exposed to the highest quality daycare. Higher adult-child ratios and more sensitive and positive caregiving in day care have consistently been associated with better cognitive performance and fewer behavioral problems in children. Some of those positive effects appear to be lasting. Findings from the NICHD-SECC found that higher quality child care was associated with a significant increase in cognitive-academic achievement scores at age 15 for children who experienced the highest levels of quality. And later research evaluating a subsample of these students found that the highest quality child care predicted higher grades and admission to more selective colleges after high school graduation. The effects were small but consistent across the outcomes from kindergarten through 12thgrade, confirming that the positive effects of high-quality child care can persist across development.

But, as research on the Quebec program found, the highest level of quality can be hard to secure. In 2005, 60% of the universal day care program sites in Quebec were judged to be of “minimal quality.” Just one-quarter of the sites provided care that met the standards necessary to qualify as good, very good, or excellent. Such findings are comparable to many other developed countries, confirming just how challenging it is for children to have access to the quality of care necessary for persistent positive gains over the long run. And these small gains have to be weighed against the risks of spending extensive hours in day care. The comprehensive evaluation of day care quality done in the NICHD-SECC found that extensive hours in day care early in life predicted negative behavioral outcomes throughout childhood and in to adolescence, even after controlling for day care quality, socioeconomic background, and parenting quality.

If our children are “at the heart of our choice,” then the research confirming that children exposed to early, extensive day care are at risk for social-emotional and behavioral challenges must be taken seriously. In the last decade, more sophisticated analytical methods have allowed social scientists to identify “cascade effects” showing how social behavioral challenges in early life predict challenges with academic competence in adolescence, which then predicts other social-emotional challenges in young adulthood. Other research identifying “cascade effects,” found that lower academic competence at ages 4 to 5 predicted social-emotional problems at ages 6 to 7, which then predicted social-behavioral problems at ages 12 to 13, followed by greater depression at age 16.

Clearly, more research is needed to understand the implications of extensive hours of day care in early life across development and into young adulthood. What we do know suggests that extensive time spent in non-maternal care in early life has effects that persist across the entire course of development. Though the effects may appear small, they matter in the lives of individual children, and they matter in the collective consequences to communities and society at large.

Jenet Erickson is an affiliated scholar of the Wheatley Institution at Brigham Young University.