Highlights

- More than half of students from married two-parent families had mostly A grades, whereas the same was true of less than half of students from most of the other family types. Post This

- Students in single-parent families and those with cohabiting birth parents had suspension rates that were one-and-a half-times higher than the rate for students with married birth parents. Post This

Students who do well in school tend to have parents who did well and went far with their own schooling. As we have shown in a previous IFS research brief, the educational attainment of a child’s birth mother and biological father are strongly associated with the child’s tested achievement in 8th grade and beyond.1 Part of the association is hereditary: among adopted or stepchildren, the students’ achievement is more closely linked to that of their birth parents than of their adoptive or stepparents.2

Educational opportunity and access to adequate schools matter as well, of course. This is shown by the many immigrants who have come to the U.S. with native talent and high aspirations but relatively little education because of the limited access to schooling they had in their home countries. Given the greater educational opportunities and resources here, the children of immigrants often do better and go farther in school than their parents did.

Students’ performance and conduct in school are also affected by the emotional support, intellectual stimulation, guidance, and discipline they receive at home. And they are more likely to get the attention, affection, and direction they need to thrive in school when they come from an intact, married family.3 One of the strengths of immigrant families with children is that they are more likely to be intact than families formed by native-born U.S. citizens.4

Beginning with the 1966 Coleman Report, a long line of studies have found that students from intact, married families do better in school than those from disrupted or unmarried families.5 My own analysis of data from a longitudinal study conducted by the U.S. Department of Education (the ECLS-K) demonstrated the impact that family transitions, such as parental divorce and remarriage, have on students’ task persistence and eagerness to learn, emotional distress, and misbehavior resulting in school disciplinary actions such as suspension.6 IFS studies of trends in Arizona, Florida, and Ohio indicate that school districts tend to be more successful and safer when more of their families are headed by married parents.7

In this new IFS research brief, I examine data from a recent federal survey to explore the link between students’ family living arrangements and three key indicators of student performance and adjustment in elementary and secondary schools across the United States. The survey was the 2016 National Household Education Survey (NHES), a nationwide mail and Internet survey of parents of 13,523 children who were enrolled in elementary and secondary schools across the country. The indicators were:

- whether the student was achieving mostly A grades in school;

- whether the parent had been contacted by the student’s school due to problem behavior that the child was exhibiting at school; and,

- whether the student had ever been suspended or expelled from school due to serious misconduct or non-cooperation.

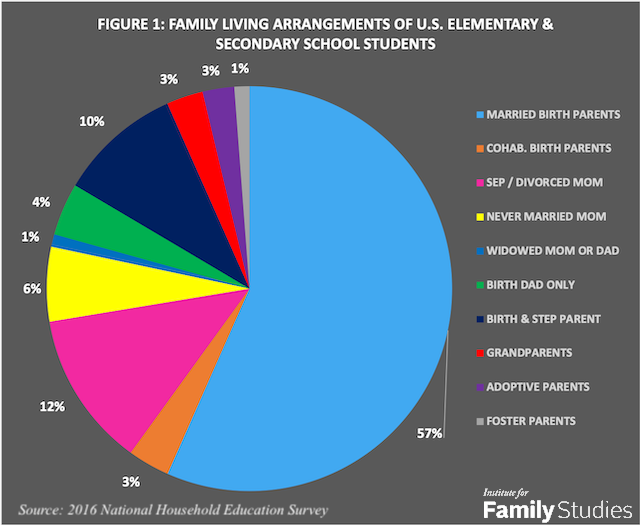

I examined the extent to which these school performance indicators were associated with the type of family in which the student lived, dividing families into 10 types. The family types and percentage of American students living in each are shown in Figure 1.

I used multiple logistic regression analyses to adjust the relationship between family type and student performance for related factors like family income, parent education, age, race, and enrolled grade level of the student, and poverty level and minority concentration of the neighborhood in which the student lived.

Children Who Live with Married Parents Do Better in School

The analyses showed that schoolchildren who live with both married parents do better on each of the three educational progress indicators. Children from married-couple families did better even after controlling for socioeconomic and demographic correlates of family structure. Here are the findings for each of the indicators in turn.

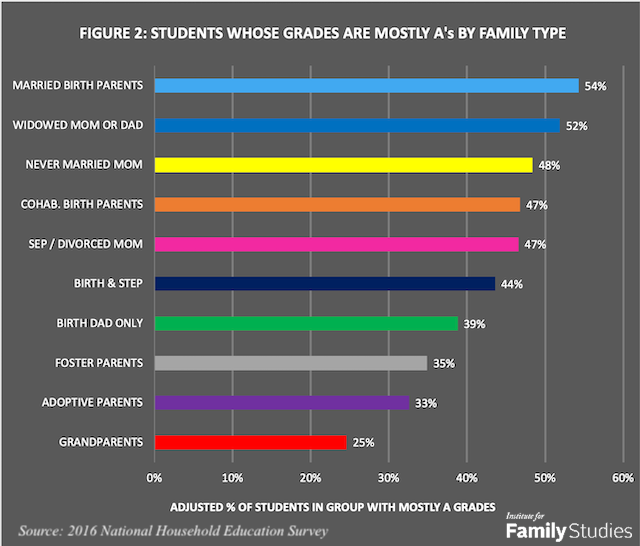

Good Grades. Nearly one-half of U.S. parents (49%) reported that their children received “mostly A’s” on their report cards. More than half of students from married two-parent families had mostly A grades, whereas the same was true of less than half of students from most of the other family types, as shown in Figure 2.

The proportion of married-parent students with A grades (54%) was significantly higher than the proportions for all other groups except for students with cohabiting birth parents, never-married mothers, and widowed mothers or fathers. The proportion for students living with grandparents (25%) was significantly lower than those for students with married birth parents, single parents, and stepparents. The proportion for adopted students (33%) was significantly lower than the proportions for single-parent as well as married-parent families.

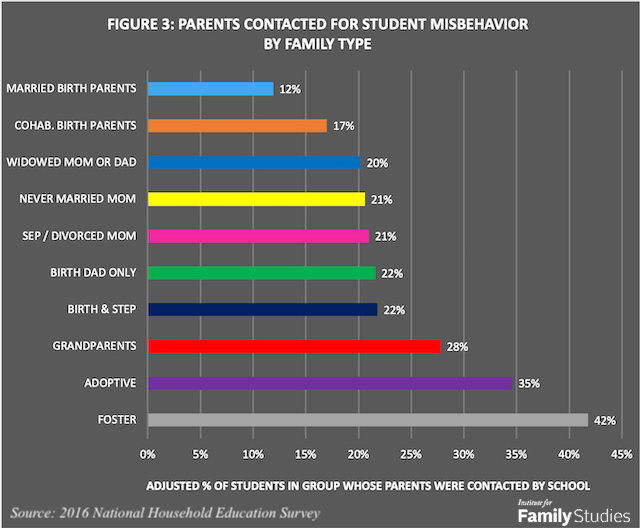

Parent Contacted by School for Student Misbehavior. Nearly one in five U.S. parents (19%) reported that they had been contacted by the child’s school at least once due to their child’s misconduct in class or on the school grounds. School contact is an indicator of student maladjustment and often foreshadows more serious disciplinary issues or learning failures to come. It may also be an indication that the student’s behavior is interfering with an orderly classroom environment, thus reducing other students’ opportunities to learn.

Differences in adjusted school contact rates between students in intact families and those in unmarried, disrupted, or reconstituted families were substantial (see Figure 3). Students from single-parent and stepfamilies were nearly twice as likely to have had their parents contacted as students living with married birth parents. Students with adoptive and foster parents were three times more likely to have had parents contacted. Contact rates for adopted and foster students remained significantly higher than those for students in single-parent families as well as in married two-parent families. After adjustment, the higher contact rate for students with cohabiting birth parents was no longer significantly different than the rate for married parents; nor was the rate for students with widowed mothers or fathers.

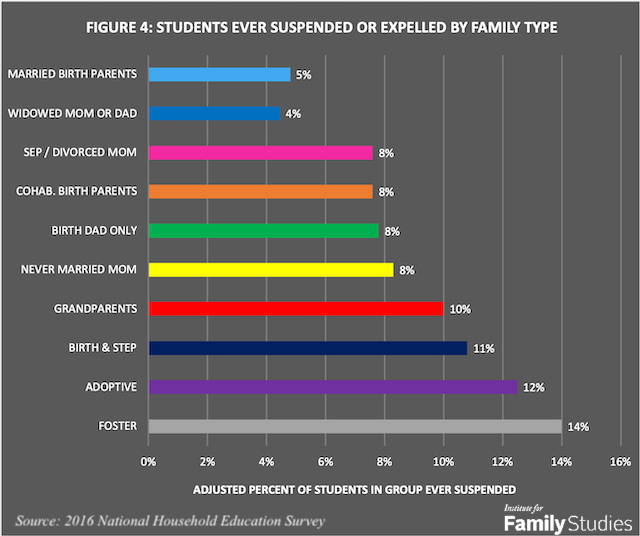

Suspension. One in 10 students in the U.S. had parents who reported that they had been suspended or expelled from a school at least once in their academic careers. Being suspended is usually an indicator of serious misbehavior by the student and also signifies that school authorities do not have confidence that the student’s parents can counsel or discipline the student in a way that will produce meaningful improvement in the student’s conduct. Adjusted suspension rates showed significant differences across family types.

As shown in Figure 4, students in single-parent families and those with cohabiting birth parents had suspension rates that were one-and-a half-times higher than the rate for students with married birth parents (8% versus 5%). Students in stepfamilies or living with grandparents had adjusted suspension rates that were about twice as high (10%-11%), while the rates for adopted and foster students were nearly three times higher (13%-14%). The differences between suspension rates for married birth parent families and those for the other family types were all statistically significant, except those with cohabiting birth parents, widowed mothers or fathers, or never-married mothers.

Family Matters for Student Success

The results of this analysis of data from a large nationwide survey of students show once again that student performance cannot be understood apart from the family dynamics. At the same time, the findings of this and earlier studies show that students from single-parent and step-families are not all alike in their academic performance and classroom behavior. Although many display temporary impairments in response to family stress, most recover and go on to do as well in school as they were doing before the disruption. When there are more lasting consequences of family change, there are usually other risk factors involved, such as parental neglect, continuing conflict between parents, domestic violence, or a family history of substance abuse, criminality, or mental illness.8 Thus, teachers and school administrators would be making a mistake in holding a stereotyped image of students from non-traditional families, especially in seeing them all as troublemakers or dropouts.

Schools are now being asked to perform functions that society used to expect families or other social institutions to perform. It is unfair and unrealistic to expect schools, no matter how well-resourced, to overcome or compensate for the family stress, churning, or lack of support and direction that too many students get at home. Rather than blaming the schools, we should be asking what our communities and larger society could be doing to assist these young people and help ensure that future generations of children have a stable, supportive family life. Changing our family culture is a challenging and controversial task. But it is one we must undertake if we are to improve educational outcomes.9

Nicholas Zill is a research psychologist and a senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies. He directed the National Survey of Children, a longitudinal study that produced widely cited findings on children’s life experiences and adjustment following parental divorce.

1. Zill, Nicholas, "Does the 'Marriage of Equals' Exacerbate Educational Inequality?" Institute for Family Studies, March 31, 2016.

2. Horn, J.M., Loehlin, J.C. & Willerman, L. (1979) Intellectual resemblance among adoptive and biological relatives: The Texas adoption project, Behavior Genetics9 (3): 177-207; Plomin, R.C. & Defries, J.C. (1983) The Colorado Adoption Project, Child Development, 54 (2): 276-289.

3. Zill and Wilcox, "What Happens at Home Doesn’t Stay There: It Goes to School," Institute For Family Studies, June 8, 2017.

4. Zill, Nicholas, "Most Immigrant Families Are Traditional Families," Institute For Family Studies, November 30, 2016.

5. James Coleman, et al. (1966), Equality of Educational Opportunity (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office); Sara McLanahan and Gary Sandefur (1994). Growing Up with a Single Parent: What Hurts, What Helps(Cambridge, MA: Harvard); Nicholas Zill & Christine Winquist Nord (1994), Running in Place: How American Families Are Faring in A Changing Economy and An Individualistic Society. Washington, DC: Child Trends. Barbara Schneider and James Coleman (eds.) (1996). Parents, Their Children, and Schools (Boulder, CO: Westview). Nicholas Zill (1996). “Family Change and Student Achievement: What We Have Learned, What It Means for Schools,” in Family-School Links: How Do They Affect Educational Outcomes? ed. Alan Booth and Judith F. Dunn (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum); Paul R. Amato and Alan Booth (2000). A Generation At Risk: Growing Up in An Era of Family Upheaval. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Paul Amato (2005). “The Impact of Family Formation Change on the Cognitive, Social, and Emotional Well-Being of the Next Generation,” Future of Children, 15, no. 2: 75-96; Robert Emery (2006) , The Truth About Children and Divorce. New York: Plume. Ariel Kalil, Rebecca Ryan, and Michael Corey (2012). Diverging Destinies: Maternal Education and the Developmental Gradient in Time With Children, Demography 49, no. 4: 1361-1383; Nicholas Zill & W. Bradford Wilcox, (2016). Strong Families, Successful Students: Family Structure and Student Performance in Ohio. Charlottesville, VA: Institute for Family Studies. Anna J. Égalité, How Family Background Influences Student Achievement (2016), EducationNext 16, no. 2: 71-78.

6. Zill, Nicholas, "How Family Transitions Affect Students’ Achievement," October 29, 2015.

7. Zill and Wilcox, "To Strengthen Florida Schools, Start With the Family," Institute For Family Studies, September 8, 2016; "Married-Parent Families Predict Graduation Rates in Florida," Institute for Family Studies, September 9, 2016; Stronger Families, Better Schools: Families and High School Graduation Across Arizona, Institute for Family Studies, September 27, 2016; "Married-Parent Families Boost Student Performance in Ohio," Institute For Family Studies, December 14, 2016.

8. Zill, Nicholas, "Substance abuse, mental illness, and crime more common in disrupted families," Institute For Family Studies, March 24, 2015; McCord, W., McCord, J. & Howard, A. (1963). Familial correlates of aggression in nondelinquent male children. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 62: 72-93; Loeber, R. & Dishion, T.J. (1983). Early predictors of male delinquency: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 94: 68-99.

9. See Nicholas Zill (1996), op. cit. ) for specific suggestions of what schools could be doing to address family change issues.