Highlights

- One finding is consistent in all analyses: older parents with minor children still at home are less happy than their empty nest contemporaries by about 5 or 6 percentage points. Post This

- Both men and women report less personal happiness and less happy marriages when there are minor children around the house. Post This

An enduring finding of the social science literature is that parents are less happy than childless adults. Most of the studies reporting this finding have relied on data from the United States, and a recent analysis of data from 22 countries by sociologist Jennifer Glass and colleagues puts American results in perspective.1 Nowhere is the parental happiness gap larger than in the United States. Indeed, American parents are notably less happy here than are their Anglophone relatives in England and Australia. In some countries, most notably Norway and Hungary, parents are actually happier than non-parents.

The Glass study also provided the most authoritative explanation to date of why parenthood makes people unhappy by exploiting national variation in public support for parenting, including differences in paid parenting leave, legally mandated vacation or sick days, and workplace flexibility. These factors account for the relationship between happiness and parenthood. To put it another way, work-family conflict can explain why parents are less happy than childless adults. There is nothing intrinsic to parenthood that makes people less happy—and nothing intrinsic to parenthood that makes people any happier, for that matter. Needless to say, most parents would say otherwise. Although willing to acknowledge the hardships of parenthood, they’re generally quick to tout its rewards.

Are the effects of children on parental happiness lasting? One way to address this question is to ask older adults. To this end, I explore the relationship between children and happiness for Americans between the ages of 50 and 70. I chose this age range for two reasons. First, almost 90% of adults have had children by the age of 50—virtually everyone who intends to become a parent has done so by then. Second, the majority of parents have also emptied the nest: less than 40% of Americans in this age group still have minor children at home. I cap the age range at 70 to exclude adults who’ve entered senescence.

Relatively few studies have looked at whether children make older parents happy. One study found no relationship between being an empty-nest parent and happiness. Another study found no relationship for men, but more complex results for women that depend upon whether mothers have good relationships with their children.

I examine the relationship between children and happiness using over 40 years of data from the General Social Survey, a national omnibus survey conducted annually or biennially since 1972. These data provide a sample size of almost 14,000 adults in the 50 to 70 age range and allow me to ascertain whether the benefits or liabilities of children for parental happiness have changed over time. In particular, I examine both overall happiness and marital happiness.

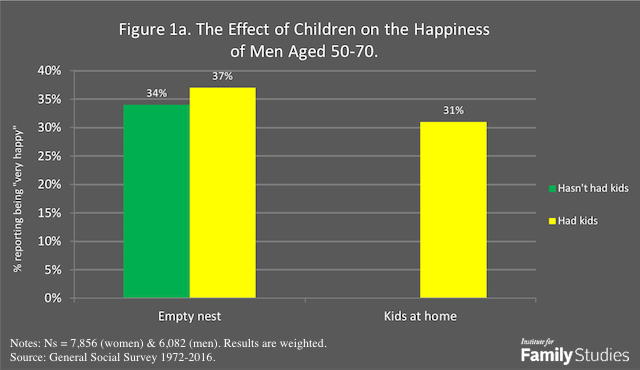

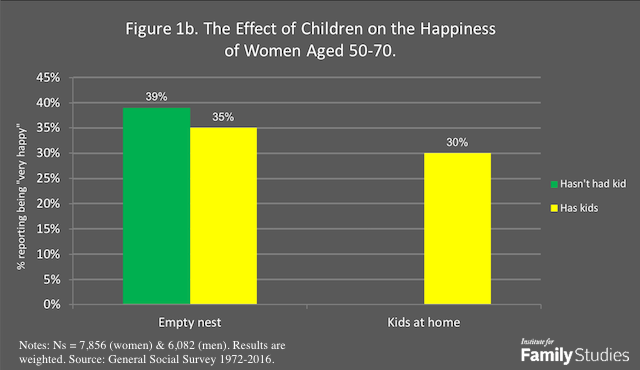

One finding is consistent in all analyses: older parents with minor children still at home are less happy than their empty nest contemporaries by about 5 or 6 percentage points, a difference that’s statistically significant (p < .001).2 This is shown in Figure 1.3

Although children in the house make men less happy, just being a parent has no appreciable impact on men’s happiness. For women, having kids is associated with a 3 or 4 percentage point decline in happiness that’s marginally significant (p < .10).

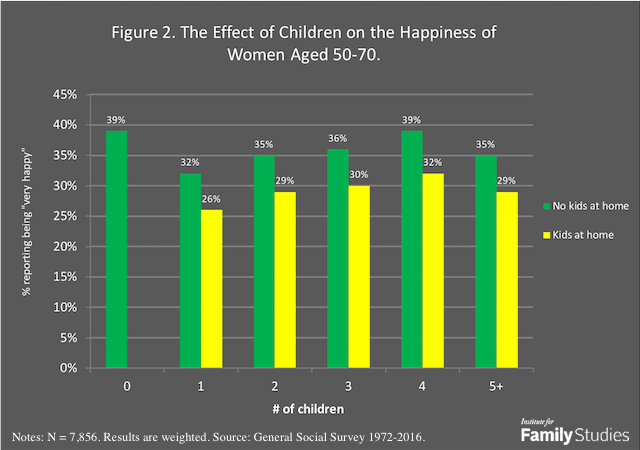

This is not a large difference, especially when held up against the happiness penalty associated with having kids at home. One possibility is that there’s variation in happiness among parents: perhaps small families make people happy but having a lot of kids does not (or vice versa). Figure 2, therefore, examines the effects of different family sizes on women’s happiness. No commensurate differences emerged for men, so the results aren’t shown.

Figure 2 shows that the adverse effects of parenthood on women’s happiness are entirely driven by women with small families.4 In particular, women with only one child are 7-percentage points less likely to report saying they are “very happy” compared to childless women (p < .01). Women with two children are a bit less happy than their childless peers, with a 4-percentage-point gap (p < .10). There are no appreciable differences in happiness for women with three or more kids; their levels of happiness are statistically indistinguishable from those of childless women.

How can these differences be explained? It’s obviously easier to care for just one or two children, so my results are counterintuitive. One possibility is that people who have more children are more likely to be invested in their families, and more deeply committed to parenthood. Familism isn’t a strong enough force to actually make parents happier than nonparents, but it does seem to offset the negative effects of parenthood.

It’s often been noted that many people have fewer children than they’d like, and this may be particularly pronounced for the mothers of small families (some childless women, in contrast, may never have intended to become parents). Perhaps these unmet family size preferences somehow redound to declines in happiness. This seems more reasonable than assuming that smaller families somehow cause women to be less happy than either childless women or the mothers of large broods.

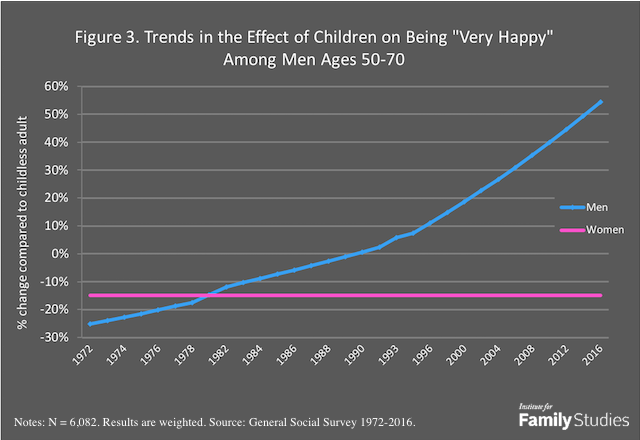

The seeming absence of a relationship between kids and happiness for men obscures a decades-long trend towards greater happiness for male parents, but not women.5 In 1972, the first year of the General Social Survey, fathers were over 20% less likely than childless men to report being “very happy.” The happiness premium for dads steadily rose over time. By the time the 2016 survey rolled around, fathers were 40% more likely than childless men to see themselves as very happy. In contrast, the happiness penalty for mothers has stayed constant over time, consistent with the results presented in Figure 1.6

The increasing fatherhood premium for men’s happiness is hardly surprising. In the past, mothers were responsible for childrearing, and fathers were relatively uninvolved. They brought home the bacon and might be the disciplinarians—“Wait until your father gets home!”—but spent far less time with their children than mothers did. That all started to change as a result of second-wave feminism in the 1960s and 1970s, and the consequent move towards a more equitable society. Sociologist Liana Sayer and her colleagues showed that married fathers spent three times as much time engaged in childcare in 1998 as they did in 1965. Growing time spent in childrearing coincided with growing parental investment and redounded to the benefits of fatherhood for individual happiness.

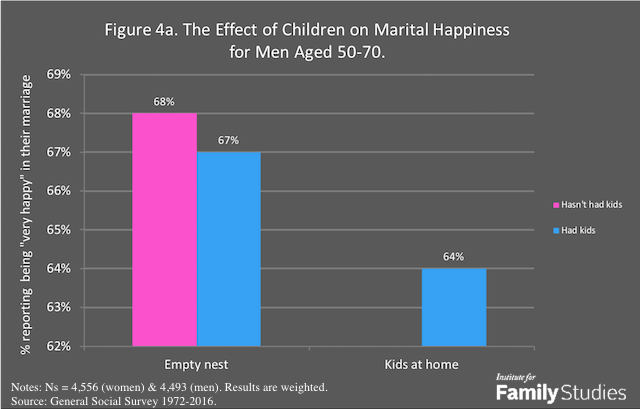

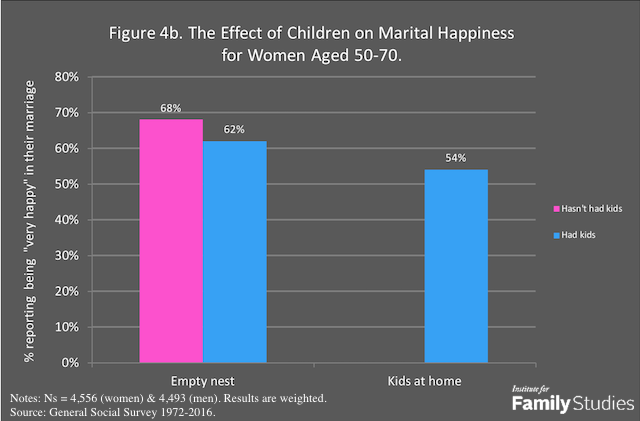

Another way to look at the effects of children concerns marital happiness, as opposed to individual happiness. The results turn out to be virtually identical: kids reduce marital happiness for women (p < .05), but not men; children at home reduce marital happiness for both men and women.

At 1 percentage point, the effect of fatherhood on men’s marital happiness is noise rather than signal. At three percentage points, the effect of having children in the house for men’s marital happiness is smaller than the effects of fatherhood on individual happiness, and only marginally statistically significant (p < .10).

The story is different for women. Mothers are six to eight percentage points less likely to be happy in their marriages than are childless women (p < .05). Having kids at home is associated with a similar reduction in marital happiness. Combined, the two child happiness penalties are substantial: 68% of childless women without kids at home are happy in their marriages, compared to 54% of mothers with kids at home.

In a subsequent analysis, I explored whether having more or fewer children affected marital happiness differently for both men and women. None of these analyses revealed statistically significant differences. In particular, mothers are less happy in their marriages than are childless women no matter how many children they’ve had.

There are two different narratives when it comes to examining the effects of children on the happiness of mid-life parents. The first concerns having minor children at home, which results almost uniformly in less happiness. Both men and women report less personal happiness and less happy marriages when there are minor children around the house. Kids are often noisy and disruptive, and they seem to take an especially large toll on older parents.

What about the effects of just having children on happiness? Here, the effects are gendered: mothers experience less happiness than do childless women, but fatherhood now makes men happier. That didn’t use to be the case as I noted earlier, but it has changed as dads have become more involved with childrearing over the past 45 years.

Parents will always be quick to proclaim the gifts and blessings their children provide, but a more detached appraisal calls into question this conventional wisdom. Perhaps children provide benefits not readily observable with the admittedly blunt psychometric instruments offered by the General Social Survey. On the other side of the fence, childless adults can be reassured by the results of this research brief: they don’t seem doomed to unhappiness by their decision to remain childless.

Nicholas H. Wolfinger is Professor of Family and Consumer Studies and Adjunct Professor of Sociology at the University of Utah. His most recent book is Soul Mates: Religion, Sex, Children, and Marriage among African Americans and Latinos, coauthored with W. Bradford Wilcox (Oxford University Press, 2016). Follow him on Twitter at @NickWolfinger.

1. Another recent study looked at 21 countries but measured average effects for the entire sample. This seems ill-advised given the national variation revealed by Glass et al.

2. A small number of GSS respondents—58 men and 51 women—report having minor children at home despite not having offspring. These are stepchildren, and perhaps a few foster children. These respondents are omitted from the figures presented here.

3. These figures are based on regression standardization of logistic regression results. Analyses control for survey year, age, race/ethnicity, education, family income, marital status, attendance at religious services, and religious denomination. The data are weighted to make the sample nationally representative. Standard errors are adjusted for the weight scheme and design effects.

4. Likelihood ratio tests confirm expansion of the variable measuring children from two to six categories for women (p < .05) but not men (p = n.s.).

5. This result is based on the statistically significant interaction (p < .05) between survey year and the dummy variable measuring whether men are parents. Information on the interpretation of this statistical model can be found here.

6. Another recent study observed a trend in happiness using GSS data but presented combined effects for men and women. The statistically significant differences between men and women are evidence that the two sexes are best analyzed individually.