Highlights

Among journalists who write about education, the stock explanation for student underachievement and school discipline problems is poverty. Yet there are examples in every school system of students from impoverished family circumstances who do well academically, as well as instances of students from affluent families who get D’s and F’s or wreak havoc in class. When poverty is overemphasized as a cause of instructional ills, other aspects of family life—such as conflict between parents or changes in student living arrangements due to divorce or remarriage—are typically ignored or underemphasized.

Indeed, it is not generally appreciated how much burden has been placed on our public schools by the revolutionary increases in divorce, cohabitation, and unmarried childbearing that took place over the last half century. We expect schools not only to cope with these changes, but also to solve any student achievement or behavior problems that might arise from dysfunctional family dynamics. And we expect them to do this without any power over the parents or guardians who care for the children most of the time.

To illustrate the importance of family transitions for student performance and behavior, and show that they are not reducible to differences in family resources, I analyzed data from a large longitudinal study of 19,000 kindergarten students that was conducted by the National Center for Education Statistics beginning in 1998.1 This study, known as the ECLS-K, followed more than 9,000 of the students through to the eighth grade. It collected information from parents, teachers, and school administrators, and directly assessed the achievement of children themselves. Because the study contains a rich array of data on family composition, family transitions, and characteristics of both resident and absent parents, it has served as the basis for several published papers on divorce and other family transitions and their relationship to student achievement and wellbeing.2 Most of these studies have not included data from the final, eighth-grade wave of the ECLS-K, which the present analysis does.

Three Different Family Trajectories from Kindergarten to Eighth Grade

Using the ECLS-K data, I looked at three groups of children, all of whose birth parents were still married when the children were in kindergarten. Those in the first group had parents who remained married, at least up to the time that the children, now teenagers, were in eighth grade.3 The parents of children in the second group divorced after the child was in kindergarten. The child then lived with a single parent, usually the mother.4 (For three-quarters of this group, the separation or divorce had occurred by the time the child was in fifth grade.) Parents of children in the third group also divorced after the child was in kindergarten (94 percent of them had done so by the time the child was in fifth grade), but the parent they lived with then remarried. Most of these children subsequently lived in a birth mother-stepfather family.5 Children whose remarried parents divorced are excluded from the analyses.

Family Resources

During kindergarten, the three groups of children were similar in terms of the economic and educational resources of their parents.6 Their financial circumstances diverged following parental divorce, and then changed again for those whose divorced parents remarried. By the time they were in the eighth grade, children in the Divorced Single Parent group had significantly lower family incomes than those in the other two groups, and a larger minority of them were living below the official poverty level. Children in the Remarried Parent group had family incomes that were higher than in the Single Parent group, and not significantly different from the Parents Stay Married group.7

Classroom Conduct in Kindergarten and Fifth Grade

During kindergarten, the three groups of children were similar with respect to their conduct in school. According to their teachers, they exhibited an above-average approach to learning tasks, paying attention well, showing eagerness to learn, and persisting in the face of challenges. Children in all three groups were less likely than the average child to be argumentative or to get into fights with other students. They were also less apt than average to appear unhappy or worried, or to withdraw from group activities. The three groups did not differ significantly from one another on these positive or negative aspects of classroom behavior.

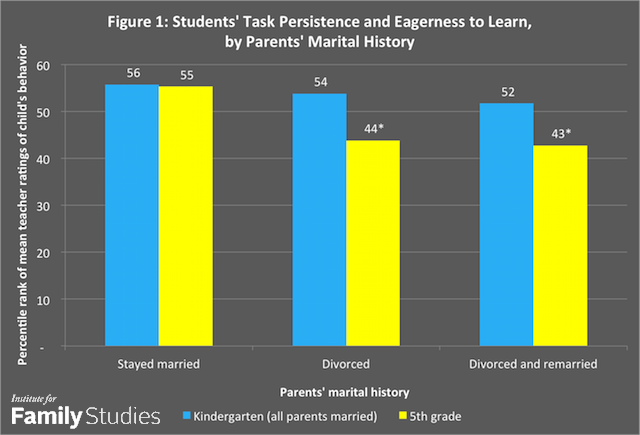

Differences in classroom behavior emerged as the children experienced family transitions. By the time they were in fifth grade, students in the Divorced Single Parent and Remarried Parent groups exhibited less positive approaches to learning tasks than students whose parents stayed married. The Single Parent children were now at the 44th percentile in teacher behavior ratings, while the Remarried Parent students scored at the 43rd percentile. As Figure 1 shows, both were significantly lower than the Stay Married group, which remained above average at the 55th percentile. The comparisons are statistically adjusted for differences across groups in student age and gender, family income and poverty status, parent education level, and racial and ethnic composition.

Note: *Different from children whose parents stayed married, p<0.05.

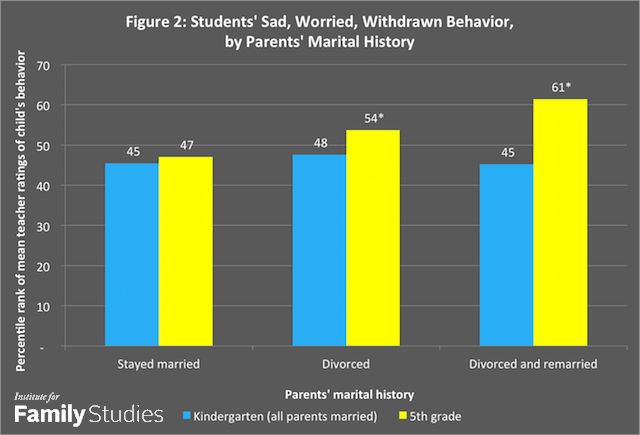

The fifth-graders from the divorced groups also showed more sad, worried, and withdrawn behavior in class than did students whose parents remained married. Figure 2 indicates that children in the Single Parent group scored at the 54th percentile in teacher ratings of these kinds of emotional distress, while children in the Remarried Parent group were at the 61st percentile. Both groups showed significantly more negative feelings than students in the Stay Married group, who were at the 47th percentile. (In this case, higher percentile ranks indicate more troubled behavior, with the 50th percentile being average across all students, including those whose parents were not married while the child was in kindergarten.) These comparisons are also adjusted for demographic and socioeconomic disparities across groups.

Note: *Different from children whose parents stayed married, p<0.05.

School Disciplinary Actions

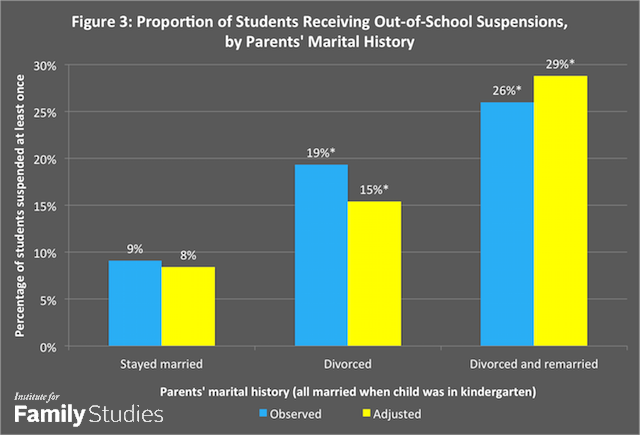

By the time the children became teenagers and reached the eighth grade, the classroom conduct problems of some of them were serious enough to lead to disciplinary action by their schools. One in four students in the Remarried Parent group had received out-of-school suspensions for classroom misconduct. The same was true for one in five students in the Divorced Single Parent group, but fewer than one in ten students in the Parents Stay Married group. After adjustments for differences across groups in student age and gender, family income and poverty status, parent education level, and racial and ethnic composition, students in the Remarried group were three times as likely to have been suspended as their counterparts in the Stay Married group, while those in the Single Parent group were twice as likely. (See Figure 3.) Both the divorced groups were significantly different from the consistently married group, but the apparent difference between the Remarried and Single Parent groups was not statistically reliable.

Note: *Different from children whose parents stayed married, p<0.05.

Problem Behavior at Home

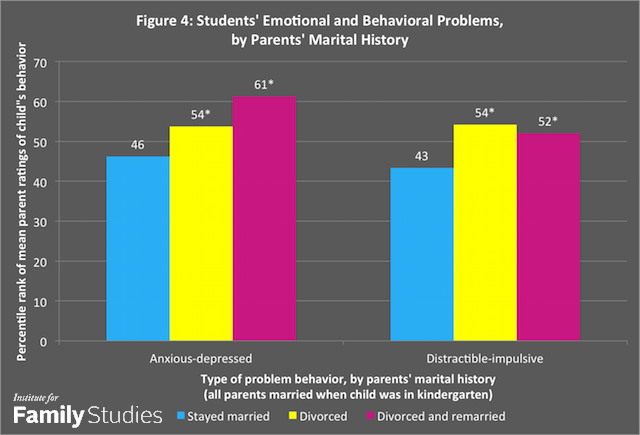

Compared to teenagers in the Parents Stay Married group, adolescents in the Remarried and Single Parent groups were more apt to seem unhappy and be bothered by fears and worries, according to their parents. Teens in the Remarried group scored at the 61st percentile on these symptoms of anxiety and depression, whereas teens in the Single Parent group scored at the 54th percentile. (Higher percentile scores indicate more negative symptoms. The 50th percentile is average.) Teens in the Stay Married group, at the 43rd percentile, were less troubled than average, as the left side of Figure 4 illustrates. These comparisons are adjusted for the same socioeconomic and demographic factors listed above.

Note: *Different from children whose parents stayed married, p<0.05.

Teens in remarried and single-parent families were also more likely than those in married-parent families to exhibit distractible, hyperactive, and impulsive behavior. Whereas those in married-parent families scored at the 43rd percentile on these symptomatic behaviors, teens in single-parent families were at the 54th percentile and those in remarried families were at the 52nd percentile. (See the right side of Figure 4.) Both the latter groups showed significantly more problem behavior than the married group, but the two divorced groups did not differ significantly from one another. Again, these comparisons are adjusted for the factors listed previously.

Grades in School

Interestingly, eighth-grade students in the three groups showed a different pattern of disparities with respect to the marks they received in school. Those in both the Stay Married and Single Parent groups had above-average grades. According to their parents, they got mostly A’s or B’s. Students in the Remarried group were below average. While not failing, they received significantly lower grades. After adjustment for socioeconomic and demographic factors, the average grades of students in the Remarried group were at the 42nd percentile, significantly lower than those of students in the Married group, who were at the 55th percentile. Students in the Single Parent group were at the 57th percentile, not significantly different from the Married group. These “report card” differences were consistent with the relative performance of students in the three groups on the reading, math, and science assessments that were administered as part of the eighth-grade round of the ECLS-K.

Is a Stable Single-Parent Family Better for Children?

In sum, both children in stable single-parent families and those in stable stepfamilies evidenced more emotional, behavior, and learning problems following the divorce, or the divorce and remarriage, of their parents. They did not evidence such problems in kindergarten, prior to the divorce. The single-parent families clearly experienced a decline in their financial circumstances following divorce. Yet this decline did not prevent children from getting good grades in eighth grade, comparable to those of students from stable married-parent families. On the other hand, the teens from single-parent families showed more symptoms of anxiety and depression at home, as well as more distractible and impulsive behavior. They were twice as likely to have been suspended from school as teens whose parents stayed married. Their problem behavior levels remained elevated after statistical controls for family income and poverty.

The teens in remarried families were better off financially than those in single-parent families, and their family resources were comparable to those of teens in stably married families. Yet they had worse grades and were three times as likely to have been suspended as the students whose parents stayed married. They also showed more symptoms of anxiety and depression at home, and more distractible and impulsive behavior. Of course, these children had experienced two major upheavals between kindergarten and eighth grade: the divorce of their birth parents and the remarriage of the birth parent with whom they were living. The children in the single-parent group went through only one upheaval: divorce.

As previous studies have shown, the financial benefits that usually accompany remarriage after divorce, and the companionship and supervision that a stepparent can provide, do not immunize children against the negative psychological effects of the stress and divided loyalties that they suffer following the divorce of their birth parents.8 In fact, the new spouse’s attempts to assume a parental role and his or her claims on the biological parent’s affection may actually exacerbate the internal conflicts that children experience.

On the face of it, the findings suggest that remaining in a stable single-parent family during the elementary-school years is better for adolescent behavior and achievement than having the custodial birth parent remarry. However, the apparent behavioral differences between the single-parent and remarried groups were not statistically reliable. The lack of statistical significance is probably due to the relatively small number of children in the single-parent and remarried-parent groups and the consequently large sizes of the standard errors around the group means. The emotional wellbeing and behavior of teens in both groups were reliably worse than those of adolescents whose parents remained married throughout their childhoods.

Family transitions like divorce and remarriage are complex processes. Not surprisingly, there is much scholarly debate about what causes what and which aspects of family life are most significant for the wellbeing of children and adults involved in these major life changes. Disentangling the complex causal web is beyond the limited scope of the present analysis. Several published papers have used sophisticated statistical methodology and the ECLS-K data to try to clarify causal questions.9 I urge the interested reader to examine them. What I hope is clear from the present analysis is that, even in relatively advantaged families, family disruption and reconstitution have effects on children that show up in school. And these effects are not simply attributable to poverty. Discussions about school discipline and educational policy would do well to recognize this reality.

Nicholas Zill is a psychologist and survey researcher who helped design the questionnaires and data collection and tabulation procedures used in the ECLS-K when he was a Vice President at the survey firm Westat.

1. West, J., Denton, K., & Germino-Hausken, E. (2000). America’s Kindergartners: Findings from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Kindergarten Class of 1998-99, Fall 1998. U.S. Department of Education: NCES Report 2000-070.

Zill, N. & West, J. (2000). Entering Kindergarten: A Portrait of American Children When They Begin School. U.S. Department of Education: NCES Report 2001-035.

2. Potter, D. (2010). Psychosocial Well-Being and the Relationship Between Divorce and Children’s Academic Achievement. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 72(4): 933–946.

Wagmiller, R.L., Gershoff, E., Veliz, P., & Clements, M. (2010). Does Children’s Academic Achievement Improve when Single Mothers Marry? Sociology of Education, 83(2): 201–226.

Sun, Y. & Li, Y. (2011). Effects of Family Structure Type and Stability on Children’s Academic Performance Trajectories. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 73(3): 541–556.

Kim, H.S. (2011). Consequences of Parental Divorce for Child Development. American Sociological Review, 76(3): 487–511.

3. There were 5,099 children in the Stay Married group.

4. There were 330 children in the Divorced Single Parent group, 288 of whom lived with their divorced mothers, while 42 lived with divorced fathers.

5. There were 140 children in the Remarried Parent group, 109 of whom lived with the birth mother and a stepfather, while 31 lived with the birth father and a stepmother.

6. The mean family income of children in the Stay Married group was $67,258; 8 percent were below the official poverty line. The mean family income of children in the Divorced Single Parent group during kindergarten, prior to the divorce, was $78,586; 9 percent were below the poverty line. The mean family income of children in the Remarried Parent group during kindergarten, prior to the divorce, was $47,597; 11 percent of them were in poverty. The proportions of children whose more educated parent had a college degree or more were 46 percent, 39 percent, and 25 percent, respectively. The income, poverty, and parent education differences across the three groups were not statistically significant.

7. When the children were in eighth grade, 49 percent of those in the Stay Married group had family incomes of $75,000 or more, while 7 percent were below the poverty line. Nineteen percent of those in the Divorced Single Parent group had incomes of $75,000 or more, while 21 percent were in poverty. Forty-five percent of those in the Remarried Parent group had incomes of $75,000 or more, while 6 percent were in poverty.

8. Booth, A., Dunn, J. (Eds.) (1994). Stepfamilies: Who Benefits? Who Does Not? Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Zill, N. (1988). Behavior, Achievement, and Health Problems Among Children in Stepfamilies. In E.M. Hetherington & J. Arasteh (Eds.) The Impact of Divorce, Single Parenting, and Stepparenting on Children. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cherlin, A. (1992). Marriage, Divorce, Remarriage. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

9. See articles listed in Endnote 2.