Highlights

- Parental favoritism—the perception that there was a favorite child in the family—may be an important factor influencing the quality of sibling relationships. Post This

- Americans are far more likely to report having a positive relationship with their parents when they did not perceive them as having a preferred child. Post This

Few aspects of childhood have a more unique or enduring impact than sibling relationships. Nearly eight in 10 Americans grew up with at least one sibling, making them a more ubiquitous presence in early life than fathers. But the ubiquity of these relationships belies what is known about their influence. Much of the debate about the influence of siblings has often centered on birth order—whether someone was an eldest, youngest, or middle child. Recent work had discounted the influence that birth order has on personality. Less attention has been devoted to understanding the way having siblings alters childhood experiences and how sibling relationships are themselves affected by family dynamics such as divorce and parental favoritism.

Most Americans with siblings report that they had at least a reasonably close relationship with their brothers and sisters growing up. Roughly eight in 10 Americans with siblings say they had a very close (41 percent) or somewhat close (37 percent) relationship with them. Twenty-two percent report they were not too close or not at all close with their siblings.

Birth order may play a role in the type of relationship siblings have with each other. Middle children are generally more likely to report having a close relationship with their siblings. Nearly half (48 percent) of middle children report having a very close relationship with their siblings, compared to 40 percent of eldest children and 35 percent of youngest children.

But other family dynamics may influence the contours of sibling relationships as well. The marital status of parents during formative years may also play a role in how close siblings feel to one another. Men who grew up with divorced parents report feeling more distant from their siblings compared to men whose parents were married report. Only 29 percent of men whose parents were divorced report having a very close relationship with their siblings growing up, compared to 41 percent of men whose parents were married for most of their childhood. The relationship women have with their siblings does not appear to be affected by parental divorce in the same way.

Although many Americans describe their relationship with their siblings as being at least somewhat close in childhood, only about half (51 percent) report being very or completely satisfied with the current relationship they have with their sibling or siblings. Thirty percent report that they are only somewhat satisfied, and 18 percent report being unsatisfied with their relationship.

Even among Americans who describe their childhood relationship as being very close, only about seven in 10 (69 percent) report being very or completely satisfied with the relationship they have with their siblings as an adult. Among those who describe their formative relationship as being “somewhat close,” less than half (46 percent) report being completely or very satisfied.

There is evidence that parents may play an important role in helping establish strong sibling connections. There is a strong correlation between how satisfied Americans are with the relationship they have with their parents and their siblings. Simply put, Americans who are very or completely satisfied with the relationship they have with their parents are very likely to feel the same about their relationship with their siblings.

Parental Favoritism

Parental favoritism—the perception that there was a favorite child in the family—may be an important factor influencing the quality of sibling relationships.

Many Americans who grew up with siblings believe their parents had a favorite child. Forty percent of Americans who grew up with siblings report that their parents had a favorite child. Sixty percent say they do not believe their parents had a favorite.

Women are more likely than men to perceive parental favoritism among siblings. Close to half (45 percent) of women compared to 35 percent of men say their parents had a favorite child.

Americans raised by divorced parents are more likely to believe their parents had a favorite than are those raised by parents who were married during their formative years. More than half (51 percent) of Americans who report their parents were divorced for most of their childhood believe their parents had a favorite child. Thirty-eight percent of Americans whose parents were married perceived their parents as having a favorite.

There is a strong correlation between how satisfied Americans are with the relationship they have with their parents and their siblings.

Who’s the Favorite?

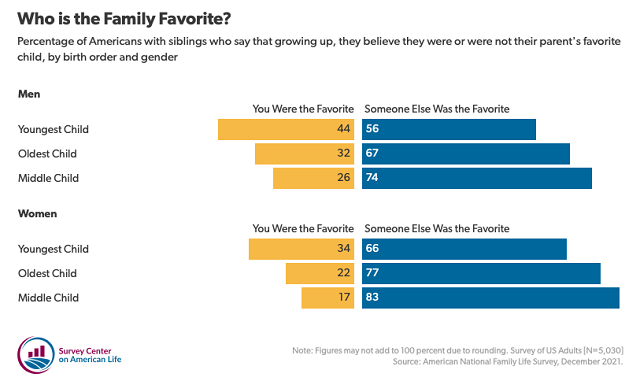

Men are much more likely than women to report being the family favorite. One-third (33 percent) of men who believe their parents picked favorites say they were the favorite in their family. Less than one-quarter (23 percent) of women believe they were their parents’ favorite.

Youngest children are generally more likely to report that they were their parents’ favorite. This is particularly true of youngest boys. Overall, 38 percent of Americans who are the youngest in their family report they were the favorite, compared to 27 percent of those who were oldest. Middle children are the least likely to say they were a favorite child; only 20 percent believe they were. Forty-four percent of men who were youngest say they were the family favorite. Women who were middle children are least likely to believe they were a favorite child; only 17 percent report that they were.

The Negative Consequences of Favoritism

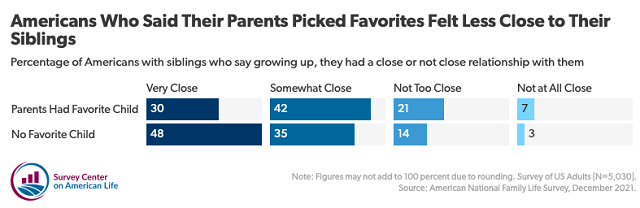

Past research has shown that parental favoritism can have lasting negative effects on relationships, personal self-esteem, and feelings of social connection. Americans who grew up in families that perceived their parents had a favorite were much less close to their siblings when they were growing up than were those who do not believe their parents had a favorite child. Among those who believe their parents had a favorite child, only 30 percent say they were very close to their siblings growing up. In contrast, nearly half (48 percent) of Americans who were raised in households in which parents did not have a favorite child say they felt very close to their siblings.

But it’s not just sibling relationships that may be affected. Americans are far more likely to report having a positive relationship with their parents when they did not perceive them as having a preferred child. More than two-thirds (68 percent) of Americans who say their parents did not have a favorite child report being very or completely satisfied with the relationship they have or had with their parents. Less than half (47 percent) of Americans who believe their parents had a favorite report being satisfied with their relationship. Even Americans who believe they were the favorite do not report having as close a relationship with their parents as those who say their parents did not have a favorite child. Just 55 percent of favorite children are satisfied with their relationship with their parents.

What’s more, perception of parental favoritism may have an enduring effect on sibling relationships later in life. Even as adults, Americans who perceived that their parents had a favorite child are much less likely to report being satisfied with their sibling relationship than those who believe their parents did not pick favorites report. Fifty-eight percent of Americans who say their parents did not have a favorite child are very or completely satisfied with the relationship they have with their siblings today, compared to 42 percent of those who say their parents had a favorite.

Parental favoritism is also associated with childhood loneliness. Americans who report that their parents had a favorite child are far more likely to report that they felt lonely growing up. Forty percent of Americans who believe their parents had a favorite report feeling lonely at least once a week growing up, compared to 18 percent of those who believe their parents did not.

Being thought of as less preferred is strongly associated with educational expectations as well. More than half (51 percent) of Americans who report they were the favorite in their family say it was expected they would go to a four-year college. Less than one-third (32 percent) of those who say they were not the favorite report it was expected they would attend college.

Birth Order, Only Children, and Childhood Loneliness

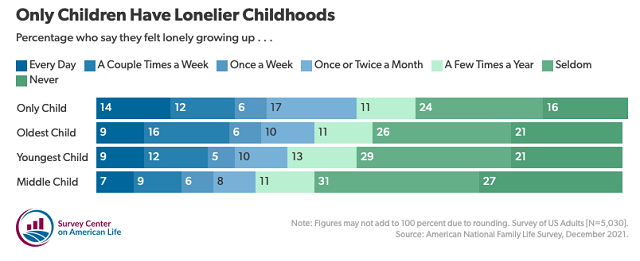

Perhaps due to their relatively close relationship to other siblings, middle children report that they felt lonely less often growing up than other Americans report. Less than one-third (30 percent) of middle children report that they felt lonely growing up at least a couple times a month. Thirty-six percent of youngest children and 41 percent of oldest children report having felt lonely this often. Only children report feeling lonely much more frequently. Nearly half (49 percent) say growing up they felt lonely at least once or twice a month.

Women who say they are only children report having felt lonely much more often during their childhood than their male counterparts did. A majority (55 percent) of women who are only children say they felt lonely at least a couple times a month growing up, compared to 42 percent of men who are only children. Nearly three in 10 (29 percent) women who are only children say they felt lonely at least a couple times a week.

Although being an only child is associated with more frequent feelings of childhood loneliness, there is little evidence to suggest these experiences have much bearing on our social lives as adults. Only children report having roughly the same number of close friends as those who grew up with siblings and are just as satisfied with their social lives today.

Despite often feeling lonely growing up, there is some evidence that middle children experience the feeling of being overlooked or forgotten. Middle children are far less likely than their siblings or Americans who were only children to say their family expected them to attend a four-year college. A majority (54 percent) of only children and about half (48 percent) of eldest children report that growing up there was a family expectation that they would go to college. Forty-three percent of youngest children report that it was expected they would attend college, but only 35 percent of middle children say this.

Daniel Cox is the founder and director of the Survey Center on American Life and a senior research fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

Editor’s Note: This essay is excerpted with permission from "Emerging Trends and Enduring Patterns in American Family Life," the February 2022 report from AEI's Survey Center on American Life.