Highlights

- Not only does cohabitation fail as a divorce-prevention safety net, it may also be associated with increased marital infidelity. Post This

- Those who had cohabited two or more times in their life before marriage were 15 percentage points more likely to have been unfaithful to their spouse than those who did not cohabit. Post This

- Research has consistently shown that the cords of this cohabitation “safety net” do not hold up under pressure, nor do they typically last long term. Post This

In June 2019, acrobats Nik and Lijana Wallenda walked across a 1,300-foot long high wire placed 25 stories above Times Square without a safety net. Though most of us will not find ourselves in that same position, sometimes the uncertainties of life can leave us feeling as though we are walking a wire of our own. To combat such uncertainty, we often look for “safety nets” that can provide cushions of security from potential disasters.

The world of romantic relationships can feel much like a balancing act. Over the past few decades, many have come to view cohabitation as a safety net for marriage relationships under the belief that it affords couples the security of testing things out without the pressure of binding commitments. Cohabitation is often viewed as a way to either strengthen a couple’s bond or recognize incompatibilities—thus acting as a “safety net” that might help prevent divorce.

However, research has consistently shown that the cords of the cohabitation “safety net” do not hold up under pressure, nor do they typically last long term. In fact, studies have demonstrated that cohabitation prior to marriage actually puts couples at greater risk for divorce. Furthermore, one of the nation’s foremost experts in this area states that cohabitation has been “consistently associated with poorer marital communication quality, lower marital satisfaction, [and] higher levels of domestic violence. . .”

Some studies have asserted that such negative consequences of cohabitation could be declining as society becomes more accepting of cohabiting. However, other researchers find that while newer samples of couples who cohabitated before marriage may demonstrate lower break-up rates in the first few years of marriage than those who did not cohabit, “the marital stability disadvantage of premarital cohabitation emerges most strongly after 5 years of marital duration and has remained roughly constant over time and over marriage cohorts.” In other words, couples who lived together before marriage may have an advantage initially as they may have fewer changes and less adaptation in comparison to those who did not previously cohabit. However, premarital cohabitation may threaten the stability of a relationship after these early years have passed. Thus, while the “safety net” might appear to provide support in the beginning, its material may not hold across time, leaving these relationships tenuous.

Research has consistently shown that the cords of this cohabitation “safety net” do not hold up under pressure, nor do they typically last long term.

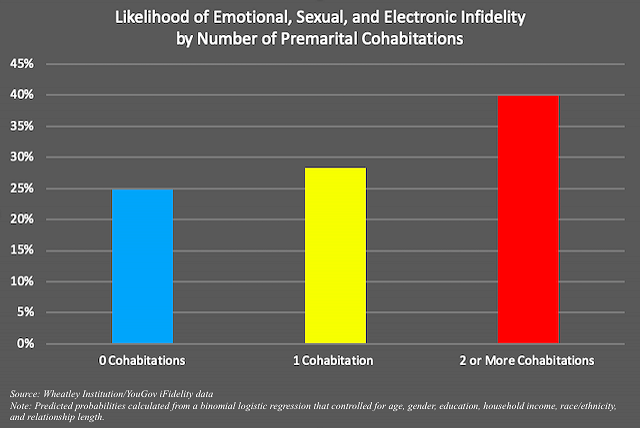

Not only does cohabitation fail as a divorce-prevention safety net, it may also be associated with increased marital infidelity. The iFidelity survey, funded by the Wheatley Institution, was conducted by YouGov in late 2018 to understand American’s attitudes and behaviors regarding fidelity. An analysis of the ever-married participants in the iFidelity data found that cohabitation may increase the likelihood of marital infidelity. Participants reported on whether they had engaged in emotional (i.e., had a secret emotionally intimate relationship), or sexual infidelity while married. The infidelity could have taken place online or “in real life.”

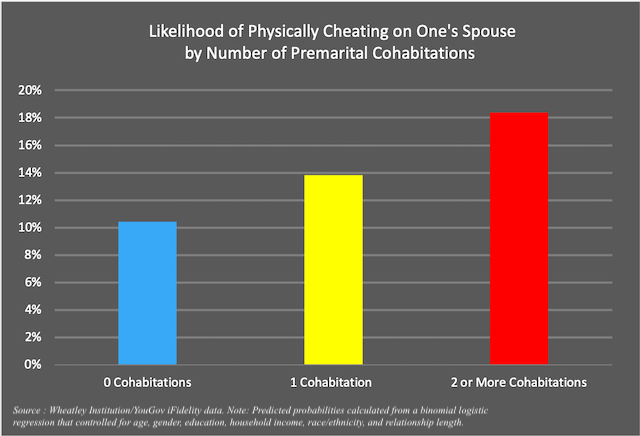

As seen in the chart below, those who had cohabited two or more times in their life before marriage were 15 percentage points more likely to have been either emotionally, sexually, or electronically unfaithful to their spouse than those who did not cohabit (to view the results when limited to physical infidelity only, please see Appendix). There was no statistical difference between those who had never cohabited and those who had cohabited only once.

These findings support previous research, as noted in The New York Times by Meg Jay, who explains that “. . . serial cohabitators, couples with differing levels of commitment and those who use cohabitation as a test are most at risk for poor relationship quality and eventual relationship dissolution.” Perhaps more to the point, these findings also support research linking cohabitation to a higher risk of marital infidelity in older samples.

If cohabitation is not the best path to a stable, faithful relationship, what can provide security and stability for marriage relationships?

One option may be premarital education. Couples taking classes together may strengthen their bond as they learn to recognize ways they can strengthen their relationship together as a team. Further, this premarital preparation does not have to occur in a formal classroom setting. It can also include simply taking the time to talk with a significant other about expectations for marriage, finding a mentor couple, or focusing on thinking about “we” instead of “me.” In short, there are plenty of ways to be intentional in preparations for a life together, and by being intentional in those preparations while dating, couples may be less likely to find themselves sliding into a serious relationship that they may not truly desire.

Taking simple steps of preparation can communicate commitment to one’s partner, allowing such preparations to act as balancing poles in marriage, providing greater stability and resistance to obstacles couples may face along their journey. When couples feel the time is right, they can take the step toward marriage without cohabiting first. By doing so equipped with adequate preparation and commitment, couples may find, just as Nick Wallenda, that “the first step is the hardest one” but that they have a lifetime of steady support and companionship as a result.

Mariah Sanders is a senior undergraduate student in the Human Development program at Brigham Young University’s School of Family Life and worked as a summer intern with the iFidelity project. Julie H. Haupt is an Associate Professor in the School of Family Life at Brigham Young University. Dr. Jeffrey Dew is an associate professor in the School of Family Life at BYU, a fellow at the National Marriage Project, and a visiting fellow at the Wheatley Institution. Timothy B. Smith, PhD is a professor of counseling psychology at Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

Appendix: