Highlights

As election season gears up, candidates have begun competing for the allegiance of American families. Among reform conservatives, pro-family policies along the lines of the $2,500 child tax credit (CTC) proposed by Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL) have garnered considerable support.1 Though a step in the right direction, the Rubio proposal falls far short in its goal of eliminating marriage penalties and providing children with the resources they need to thrive in stable families. Low-income families, especially, still face a number of obstacles that Rubio’s CTC leaves unaddressed. With no proposed alternatives, what’s a reform conservative to do?

While Bernie Sanders has suggested we look to Denmark for guidance, reform conservatives need only look to our friendly northern neighbor for guidance on how to make our tax/transfer system more pro-family. It was over two decades ago in Canada that the so-called “Family Caucus” played a key role in transforming the country’s hodgepodge of tax/transfer programs into a single pro-family child tax credit—with promising results.

The Family Caucus was a coalition of Progressive Conservative members of Parliament (MPs) concerned with ensuring support for families in public policy. The Family Caucus was formed in 1989 when Progressive Conservative MP Al Johnson gave an impassioned speech railing against marriage penalties in the tax code that favored cohabiting couples over married couples. He believed marriage penalties were weakening family life in Canada. Johnson soon found himself surrounded by MPs holding similar views, leading him to form the Family Caucus within the Progressive Conservative government of Brian Mulroney.2

After successfully restoring equal treatment of married couples in the tax code, the caucus turned its attention to the treatment of families in the tax-transfer system. At the time, Canada had three overlapping child benefit programs: a family allowance, a refundable child tax credit, and a nonrefundable child tax credit. (A refundable credit allows families to claim the full value of the benefit even if it exceeds total tax liability, while a nonrefundable credit limits the value of the benefit to income tax liability.) All three programs were supposed to recognize the importance of families for raising children, but years of neglect resulted in considerable erosion of their value by 1991 and confusion for parents. Recognizing the importance of a firm economic foundation to the stability of families, the Family Caucus set out to consolidate these disparate programs into a single refundable child tax credit targeted toward families most in need. Making the tax credit fully refundable—and thus available to all families—was the key to its success.

Family Caucus members saw a refundable child tax credit as a way to strengthen families relative to alternative welfare and childcare proposals. Increasing welfare benefits might help relieve child poverty, but it would penalize work and marriage because recipients who entered the workforce or got married would have their benefits sharply reduced. Publicly provided childcare could encourage work but disfavored families where one parent chose to stay at home with the children.

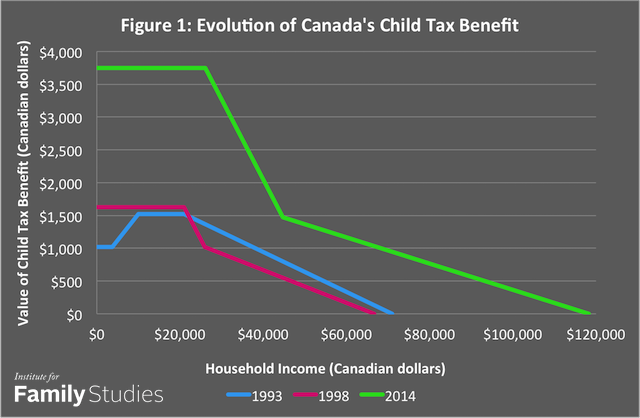

In contrast, as a broadly universal cash benefit, a refundable CTC would eliminate marriage penalties, encourage work, and respect the childcare choices of all parents. Under strong pressure from the Family Caucus, the Mulroney government introduced the Child Tax Benefit (CTB) in 1992. Acknowledging the CTB’s advantages, subsequent governments have expanded it several times, as the below figure indicates. The current maximum benefit is C$3,750 (US$2,973) for the first child, with the average families receiving C$2,437 (US$1932) in benefits. The incoming government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has promised to raise the maximum benefit to C$6,400 (US$5,074) for families with young children.

Source: Canada Revenue Agency, various years.

Research on the effects of the tax credit finds it helps families in two ways. First, it channels resources to low-income families for investments in intergenerational mobility such as basic nutrition and education. Second, families use the tax credit to stabilize family life during times of change. The extra income “reduces stress and improves household relations, increases the chance and opportunities for employment and eases financial burdens,” in the words of one team of researchers.3 They also found that the expansion of benefits is correlated with a substantial decline in alcohol and tobacco consumption, which implies parents experience less stress and children have an improved home environment when benefits are more generous. (Unfortunately, no detailed statistical analysis is available on whether or how the CTB has affected trends in family structure.) In contrast, recent analysis of Quebec’s publicly subsidized childcare program shows that it resulted in “more hostile, less consistent parenting, worse parental health, and lower-quality parental relationships.”4 Not only are childcare programs unnecessarily expensive and complex, they are inferior to the simple alternative of channeling resources directly to families to use as they see best.

The CTB also succeeded in substantially reducing or eliminating existing marriage penalties in the tax/transfer system, especially for low-income families. By providing child benefits to parents regardless of unemployment and income, the tax credit eliminates the nefarious situation where two low-income cohabiting parents will lose benefits if they choose to get married.5

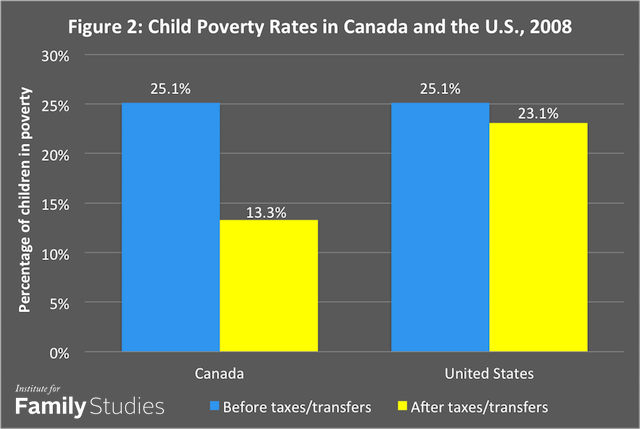

Most importantly, these pro-family tax credits are a major contributor to the alleviation of family poverty. At the height of the Great Recession, Canada’s child poverty rate was a full ten percentage points lower than the U.S. rate once government support was taken into account. This is because, unlike the U.S. CTC, Canadian families do not lose their CTB when one or both parents temporarily lose their job. And unlike traditional welfare programs, which can trap families in poverty, the CTB is pro-work: after its expansion, there was a marked decline in reliance on welfare paired with an increase in hours worked among families.6

Source: Bradshaw, J., Y. Chzhen, G. Main, B. Martorano, L. Menchini, C. de Neubourg (2012), “Relative Income Poverty among Children in Rich Countries,” Innocenti Working Paper No. 2012-01, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Florence.

Much like the situation in Canada over two decades ago, American families now face a hodgepodge of ineffective tax/transfer programs racked with marriage penalties and poverty traps. Reform conservatives interested in pro-family policy reforms should take a cue from the Family Caucus and consider consolidating some of these programs into a single refundable child tax credit. In my next piece, I will suggest how American policymakers might go about doing this.

Josh McCabe is the Freedom Project Postdoctoral Fellow at Wellesley College, where his current research project looks at the politics and consequences of child-related tax credits in the United States, Canada, and United Kingdom. Follow him on Twitter @JoshuaTMcCabe.

1. YG Network (2014), Room to Grow.

2. York, G. (1992), “Tory Politicians Form Family Compact,” Globe and Mail. 3 June: A1.

3. Jones, L., K. Milligan, and M. Stabile (2015), “Child Cash Benefits and Family Expenditures: Evidence from the National Child Benefit,” NBER Working Paper #21101.

4. Baker, M., J. Gruber, and K. Milligan (2008), “Universal Child Care, Maternal Labor Supply, and Family Well‐Being,” Journal of Political Economy 116(4): 709-745.

5. Carasso, A. and C.E. Steuerle (2005), “The Hefty Penalty on Marriage Facing Many Households with Children,” Future of Children 15(2): 157-175.

6. Milligan, K. and M. Stabile (2007), “The Integration of Child Tax Credits and Welfare: Evidence from the Canadian National Child Benefit Program,” Journal of Public Economics 91: 305-326.