Highlights

- While the tax system does not pose too much of a problem except for the highest earners, the benefit system punishes lower earners for tying the knot. Post This

- Marriage penalties faced by single Americans correlate with their marriage behavior, suggesting that these policies, beyond being unfair, could significantly discourage marriage. Post This

- “For 25-year-old, low-income females with children, the marriage tax reduces their chances of being married ten years later by 7.52 percent,” per a new NBER working paper. Post This

“Marriage penalties,” in which the tax-and-transfer system punishes people for getting married, have long been a troubling aspect of American social policy. A couple might face a higher tax rate after marriage than they did as singles, or their combined income might make them ineligible for welfare benefits they previously received.

A new working paper from Elias Ilin, Laurence J. Kotlikoff, and Melinda Pitts investigates this problem in an interesting and novel way. It starts with real data on Americans’ finances, and then runs elaborate simulations estimating how individuals’ spending will fare over their entire lives if they marry or stay single. The upshot is that while the tax system does not pose too much of a problem except for the highest earners, the benefit system punishes lower earners for tying the knot. Further, the marriage penalties faced by single Americans correlate with their marriage behavior, suggesting that these policies, beyond being unfair, could significantly discourage marriage.

The study’s approach is clever and a little tricky in some ways, so let’s dig in.

The researchers start with data on Americans ages 20 to 49 from the Survey of Consumer Finances, but real data are messy. Some people are currently married, others single. And of course, getting married can mean different things in different circumstances—one's new spouse might be unemployed or a billionaire, and that difference should matter in terms of tax liability. You didn’t face a “marriage penalty” if you married a Google executive and paid higher taxes as a result.

To sidestep these issues, the study “pseudo-divorces” or “singleizes” all the married couples, assigning the kids to the wife (or the primary survey respondent for same-sex couples) and dividing up assets evenly. Then, using a simulation tool called The Fiscal Analyzer, it contrasts single life with “clone marriage,” in which each person marries an exact financial clone of him or herself (though without kids).

The difference is calculated in terms of lifetime resources, not just the impact on the current year’s taxes and benefits. And it’s calculated in all 50 states and D.C., taking into account the tax and benefit rules of each place and programs ranging from income taxes to Social Security to Obamacare.

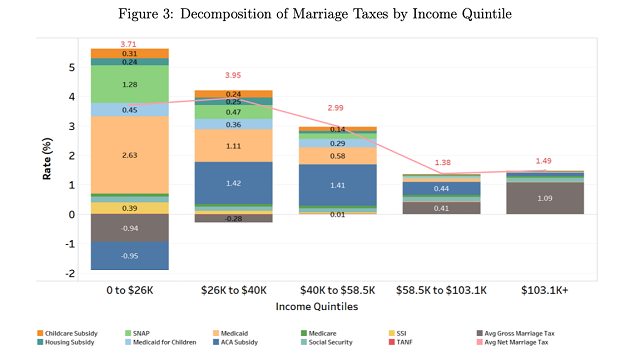

If two identical people face higher taxes or receive less in benefits than they would have as singles, they pay a marriage penalty in the form of “gross taxes” or “transfer claw-backs,” respectively. And if those two effects combined make the couple worse off married, they pay an overall marriage tax. This chart from the paper provides a handy summary of the results by income, breaking down the bonuses and penalties by the policies that created them. Note, however, that these depict the benefits that individuals and couples are eligible for, not that they necessarily use (more about that in a second); they might be seen as potential marriage penalties.

Put simply, the system discourages marriage. For example, two lower-income Americans (the left-most bar) might gain access to Obamacare subsidies by marrying—and also come out better at tax time thanks to various credits—but these effects are swamped by others. Those ACA subsidies could come at the cost of losing Medicaid as an even cheaper health-care option, for example, and the couple may also lose numerous other benefits such as food stamps. At the higher end of the income spectrum, the consequences are less dire—a lower percentage is lost out of higher lifetime spending but marriage is still penalized, this time more via higher taxes.

The authors break the results down further by sex and children. Women with kids fare worst, losing 2.71% of their total resources from marrying a clone. For all combinations of sex and kids, the tax system is slightly pro-marriage, but it’s swamped by the anti-marriage effects of the benefit system.

The paper then links these marriage penalties to actual marriage behavior, based on real-life people who were single in 2017 (captured in the American Community Survey). After controlling for numerous variables—state of residence, race, education, etc.—the marriage-tax rates appear to have a substantial impact: If two single people were otherwise similar, but one faced a higher marriage tax, that person was less likely to get married in 2018. “A one-percentage point increase in the marriage tax rate decreases the probability of marrying for females with children by 3.69 percentage points and 1.12 percentage points for females without children,” the authors write. For males, a one-point tax increase translates to a 0.21-point decline in the probability of marrying if they have kids and a 1.54-point decline if not.

There are some inevitable complications here. For example, as the authors discuss, in calculating marriage penalties, the simulations assume that people use all the benefits available to them, which in practice does not always happen, for numerous reasons including “lack of information, stigma, complicated application procedures, and benefit rationing in some programs.” Therefore, the results are an “upper bound” on the marriage taxes couples actually pay. When the simulations take account of benefits’ real-life take-up rates, the marriage-tax estimates are lower than the unadjusted ones.

However, marriage taxes still correlate strongly with actual marriage decisions. “For 25-year-old, low-income females with children, the marriage tax reduces their chances of being married ten years later by 7.52 percent,” the authors write. “Correction for program participation makes little difference to this value, with a reduction in the probability of being married 10 years later of 6.24 percent."

The process of “singleizing” survey respondents, marrying them to “clones,” and then simulating their entire fiscal futures creates other limitations too, of course. The single version of someone might not reflect what he or she would actually look like if single. (Stay-at-home mothers out of the labor force are especially tricky in this regard; when “singleized,” they become single moms with no income, though the algorithm doesn’t assume they’ll be permanently without income.1 Clone marriage neglects the experience of couples with different earnings, though the authors show their results are roughly similar when they assume individuals marry spouses with either 50% higher or 50% lower earnings.

Ilin, Kotlikoff, and Pitts have made an important contribution here, showing how many aspects of U.S. policy treat people differently—often less favorably—when they get married. Addressing these penalties should be a priority.

Robert VerBruggen is an IFS research fellow and a fellow at the Manhattan Institute.

1. As Kotlikoff explained to me in an interview, projected future earnings are based on a mix of current earnings and the earnings of similar people. There are more details in this paper.