Highlights

- Children of religious conservatives are more religious than others, and more religiously similar to their parents. Post This

- While the challenges of passing on the faith remain considerable, religious conservative parents are managing that challenge somewhat better than others. Post This

- Children of religious conservatives are more likely to match the religiosity of their parents, and when they stray, they tend not to stray as far. Post This

The Western world has long shown signs of religious decline, with emptying pews and rising rates of religious nonaffiliation and atheism. For many years, the United States was believed to be an exception to this general pattern, showing a robust religious life in the face of modernization. But research since the early 2000's suggests that even in the U.S., religious decline is now evident, with the proportion of religiously unaffiliated Americans (commonly known as the "nones") rising from around 5% in the early 1990s to nearly 30% in 2021, and showing no signs of slowing. This is best explained by a process of cohort replacement: each generation is less religious than the last.

It is with good reason, then, that parents and churches alike feel a growing sense of urgency as they ask what they can do to keep their children in the faith. Some call for a style of religion that seeks to be more modern and relevant, and hence more appealing to younger generations. Others call for the formation of close, intentional communities where religious values are strong and corrosive influences are minimized, in an approach pithily labeled "the Benedict option." Still others simply throw their hands up and feel they can do little except trust the matter to God.

Coming from a different angle, social scientists have also long been interested in which factors contribute to the transmission of religion between generations, and research has taught us a great deal. In the modern United States, parents are the most important agents of religious transmission, playing a stronger role than congregations, youth groups, or other potential areas of influence. When parents are religiously similar to each other, practice what they preach, and maintain good relationships with their children, they are more likely to pass on their beliefs. Religious tradition matters, too: children raised in groups with a strong sense of identity, such as Latter-Day Saints or Black Protestants, are more likely to stay religious in adulthood.

My study published recently in the journal Sociology of Religion reveals another important factor in religious transmission: parental religious conservatism. Specifically, using the National Study of Youth and Religion (NSYR), I looked at the link between how parents identified religiously (conservative, moderate, liberal, or none of these) when their children were adolescents, and how religious their children were 10 years later in young adulthood. All the findings were consistent: children of religious conservatives are more religious than others, and more religiously similar to their parents. This holds even after accounting for other factors we know are important, such as religious tradition or parental political ideology.1

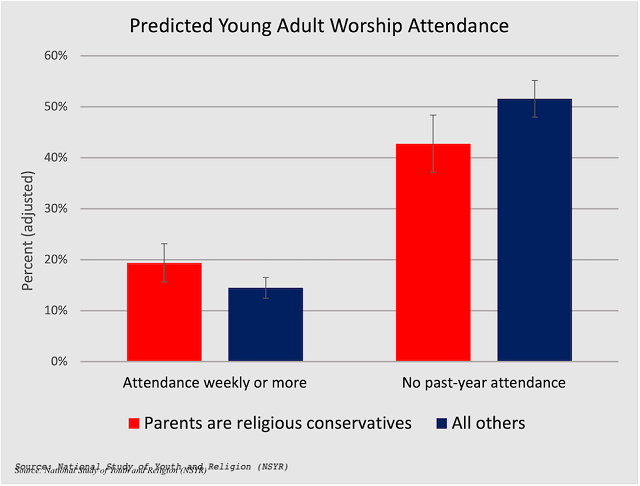

For instance, children of religious conservatives have a 19% chance of attending worship services at least weekly. This may sound low, but it's higher than the 15% chance we see in people from moderate or liberal families. At the other extreme, an estimated 43% of the children of religious conservatives report no worship attendance at all in young adulthood, compared to 52% for everyone else.

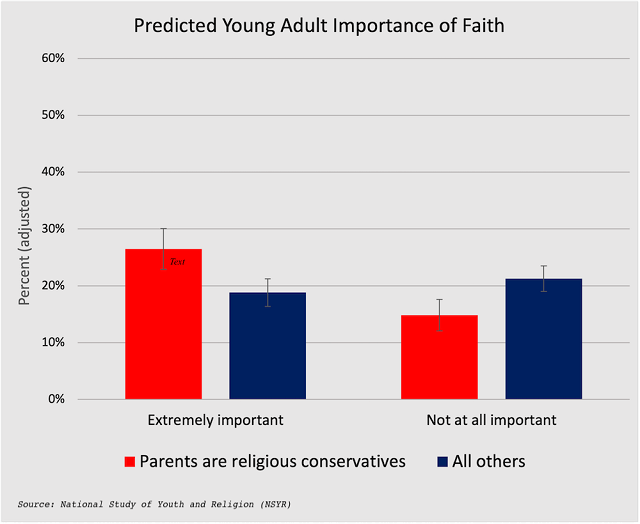

We see something similar for the importance of faith. Around one-quarter of children of religious conservatives are predicted to say faith is "extremely important," while 15% say it isn't important at all. In contrast, less than a fifth of other young adults say faith is "extremely important," while an estimated 21% consider it irrelevant to their lives.

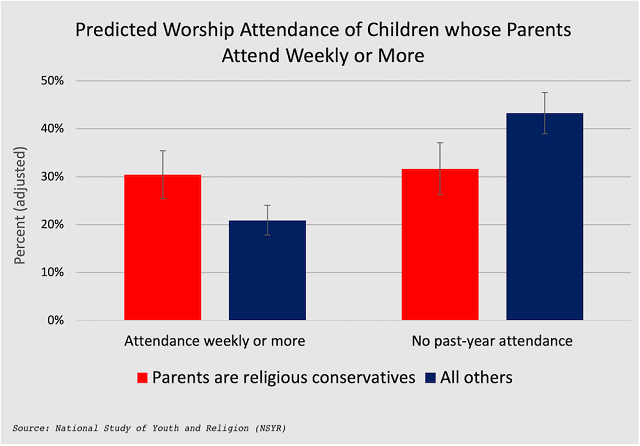

So, children of religious conservatives are themselves more religious than their peers. But there is another question to consider: Are these children more similar to their parents? In other words, are religious conservative parents more effective at transmitting their faith to their children? For illustrative purposes, we can try to answer this by just taking the most religious group of parents and seeing how likely it is that their children will be similarly religious. If we only look at parents who attend services weekly or more, we see that children of religious conservatives are nearly 10 percentage points more likely to also report high attendance, and less likely to report no attendance, than their peers from non-conservative families.

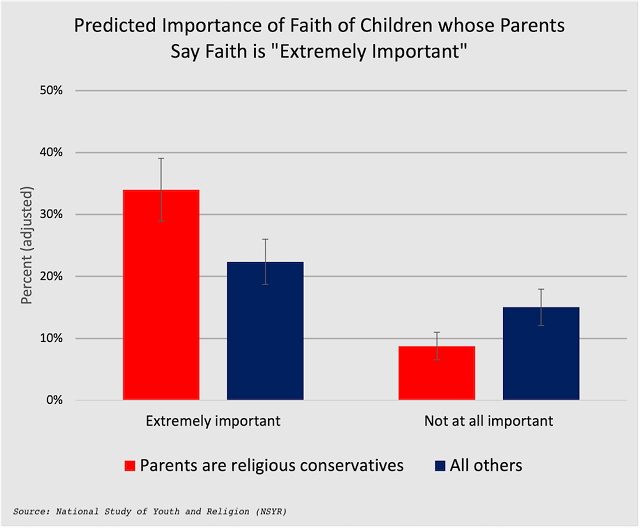

When we examine children's importance of faith only among parents who report the highest level of faith themselves, we see children of religious conservatives are about 12 percentage points more likely to agree that faith is of utmost importance, and 6 percentage points less likely to say it doesn't matter at all. Children of religious conservatives are more likely to match the religiosity of their parents, and when they stray, they tend not to stray as far.

In brief, yes, religious conservative parents are more effective at transmitting their faith to their children. We shouldn't overstate the effect here, though. Children from all groups are, on average, less religious than their parents. Religious conservative parents still face an uphill battle in passing on the faith. But they do fare somewhat better than their moderate or liberal counterparts, even those who are just as religiously committed themselves, belong to the same religious tradition, and are similar in other respects.

What explains these results? It may first be helpful to ask what makes someone identify as a religious conservative in the first place. This probably isn't any one thing so much as a cluster of characteristics that tend to go together: biblical literalism, belief in a personal and engaged God, a sense of tension with the larger society, moral absolutism, or sexual traditionalism, to name a few. And what do religious conservative parents do differently? My study reveals a straightforward answer: they are more active in their children's religious socialization. Specifically, the children in the study were asked in adolescence how often their families discuss “God, the Scriptures, prayer, or other religious or spiritual things together.” This one factor explains about half of the difference in religious outcomes between children of conservatives compared to everyone else, far more than anything else I examined. To pass on religion, parents need to make it a part of daily family interactions.

This may sound obvious, but it runs counter to many parents' instincts regarding the religious upbringing of their children. Christian Smith and his colleagues have shown the ways that parents worry about coming on too strong when teaching their children about religion. Parents want to make sure they give their kids room to explore religious questions for themselves, and don't want to do anything to alienate their kids or provoke teenage rebellion. These are legitimate concerns, and if children feel like religion has been “rammed down their throats,” this may serve to push them away.

But my study suggests that, on average, the barrier to passing on the faith is not too much religious socialization, but too little. Taking too light a touch with religious parenting comes at a cost. If kids do not receive a clear and consistent message from their parents that religion is important, they are likely to simply conclude that it is not important. In eras past, religion may have been pervasive enough that parents could assume children would receive religious socialization from the surrounding society, from peers or other adults in their lives, or even at school. But in 2022, if they do not encounter religion in a serious way at home, they are not likely to get it anywhere else. While the challenges of passing on the faith remain considerable, religious conservative parents are managing that challenge somewhat better than others, and their secret is simple: when it comes to religious parenting, be hands-on.

Jesse Smith is a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at The Pennsylvania State University.

Editor's Note: The opinions expressed here are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.

1. Specifically, all numbers reported and presented in figures are adjusted for parent religious tradition, whether parents were married, whether they were of the same religion, their highest level of education, and their political ideology, as well as children’s age, race, and residence in the South, all measured when children were in adolescence.