Highlights

- In all countries, for both men and women, having children in the home was associated with greater meaning in life—and this was true across all age categories, education levels, and partnership statuses. Post This

- Mothers in Central and Eastern Europe and Southern Europe were most likely to express low life satisfaction, while mothers in the Nordic countries were more likely to express high life satisfaction, all else being equal. Post This

- Older mothers, mothers with a high level of education, and married mothers reported higher levels of life satisfaction. Post This

Poets, philosophers, novelists, and songwriters have long opined on the meaning of life. A common recent view is Nietzsche’s assessment that life is meaningless, or equivalently, Douglas Adam’s suggestion in the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy that the meaning of life is “42.” Leo Tolstoy, however, thought that giving to others gave life meaning. Likewise, Nobel Laureate Bob Dylan sang: “Have a bunch of kids who call me ‘Pa,’ that must be what it's all about.” New research published in the Journal of Marriage and Family weighs in on the issue and finds that for modern Europeans, Tolstoy and Dylan were on to something.

Sociologists Ansgar Hudde and Marita Jacob used data from the European Social Survey with more than 43,000 respondents ages 18–49 from 30 European countries and Israel to examine the differences in scores on satisfaction and meaning in life between those with minor children in the home and those without. Life satisfaction was measured by a question that asked: “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days?” Meaning in life was measured with the level of agreement with the statement, “I generally feel that what I do in my life is valuable and worthwhile.” The researchers also examined how these measures varied with the respondent’s country, age, level of education, and partnership status.

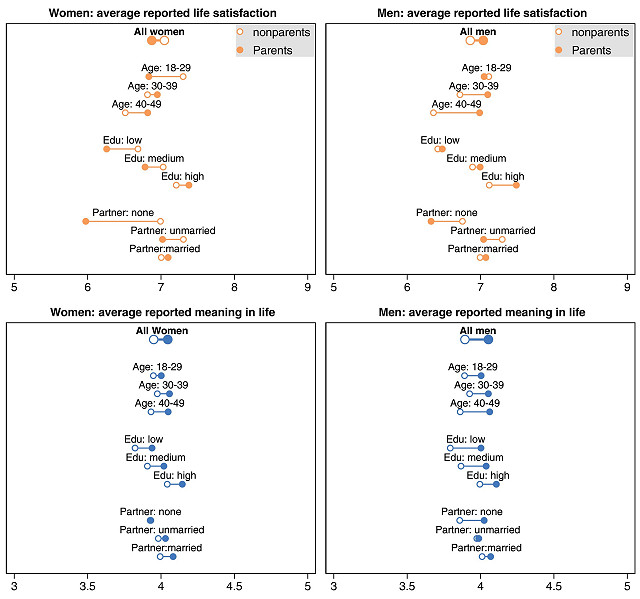

The figure below gives the averages on the measures of life satisfaction and meaning in life for parents (solid dots) and non-parents (hollow dots) for men and women separately within different age, education, and partnership categories.

Figure 1. Comparison of life satisfaction and meaning in life levels between parents and nonparents across groups by age, education, and partnership status. Life satisfaction ranges from 0 to 10, meaning in life from 1 to 5.

For all women combined, life satisfaction was highest among women without young children in the home, whereas for all men combined, life satisfaction was highest among men with young children in the home. For women, there were considerable differences by age, education and partnership status. Young women with children in the home reported significantly lower life satisfaction than nonmothers in the same age group. Older mothers, mothers with a high level of education, and married mothers reported higher levels of life satisfaction. Fathers reported higher life satisfaction in all categories except the youngest age group, unmarried men, and men with no partners. Both male and female parents reported more meaning in life than nonparents, and this was the same across all age, educational, and partnership categories.

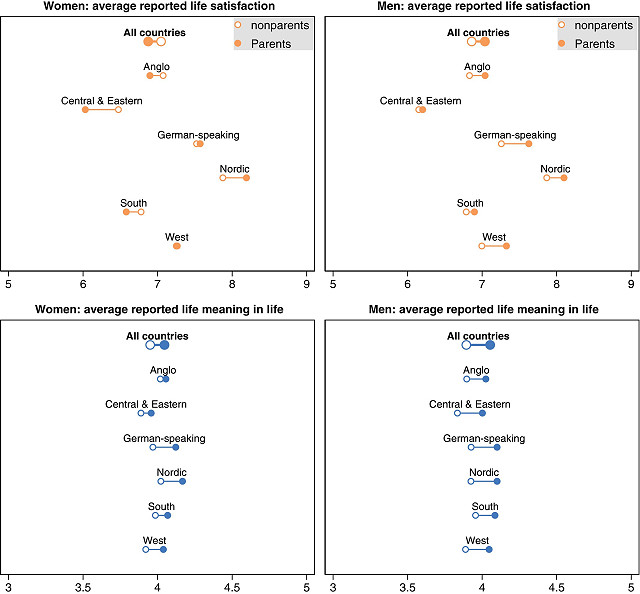

The researchers also examined how these results varied by country. They found that especially among women, there was substantial variation by country (see figure below), with parenthood being associated with higher life satisfaction among women in the Nordic countries; lower life satisfaction among women in English-speaking, Southern European, and Central and Eastern countries; and little difference between parents and non-parents in the German-speaking and Western European countries. This is perhaps not surprising, given that Nordic countries are notable for having very strong support for working mothers, including nearly a year of paid leave after childbearing for both parents.

Among men, parenthood was associated with higher life satisfaction in all countries, but the difference between parents and non-parents was smaller in Southern European and Central and Eastern countries and larger in the English-speaking, German-speaking, Western European, and Nordic Countries. With regard to meaning in life, both male and female non-parents had lower scores on meaning in life in all countries, with parents in the German-speaking and Nordic countries showing slightly higher scores on meaning of life than parents in other countries.

Figure 2. Comparison of life satisfaction and meaning in life levels between parents and nonparents across country clusters. Note: Israel not included in these analyses because it could not be grouped into any of the country clusters. Life satisfaction ranges from 0 to 10, meaning in life from 1 to 5.

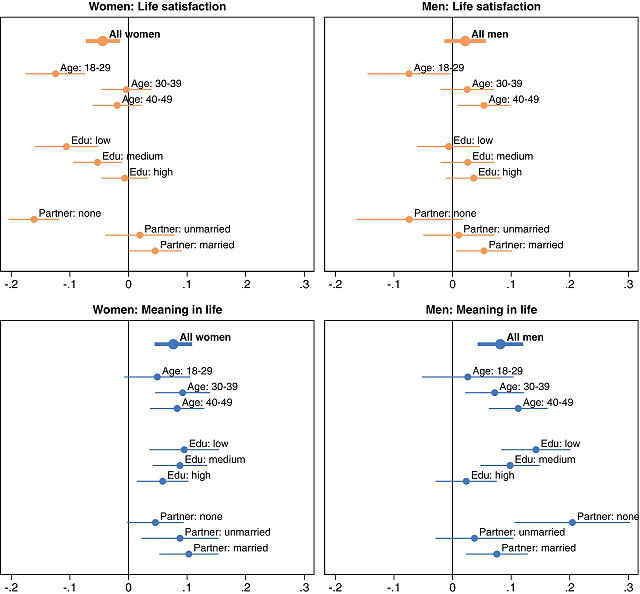

Because the simple average scores on satisfaction in life and meaning in life are influenced by other factors besides country, age, education, and partnership status, the researchers also created multivariate models that controlled for these factors as well as for family background and individual religiosity. These models found that all else being equal, women with children at home reported lower life satisfaction, and men with children at home reported higher life satisfaction (see figure below).

These multivariate results showed that all parents with children, across all age groups, educational categories, and partnership status reported greater meaning in life than non-parents—even unpartnered women with children.

However, these models showed that unpartnered women with children displayed significantly less satisfaction in life than partnered and married women with children, all else being equal. Given that unpartnered women must shoulder most of the burdens of parenting by themselves, it is not surprising that their satisfaction in life would be lower. In contrast to the results for life satisfaction, these multivariate results showed that all parents with children, across all age groups, educational categories, and partnership status reported greater meaning in life than non-parents. Even unpartnered women with children expressed significantly more meaning in life than women without children.

Figure 3. Effect of children in the home on life satisfaction and meaning in life by age, education, and partnership status.

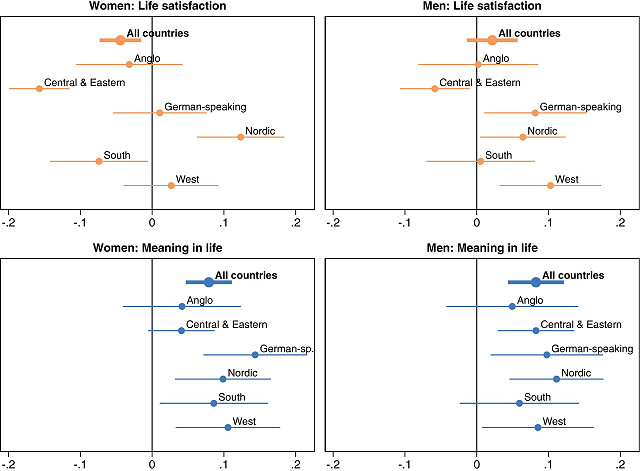

Finally, the last figure (below) shows the effect of children in the home from the multivariate models by country cluster. Mothers in Central and Eastern Europe and Southern Europe were most likely to express low life satisfaction, while mothers in the Nordic countries were more likely to express high life satisfaction, all else being equal. Fathers expressed lower life satisfaction only in Central and Eastern European countries, and higher life satisfaction in German-speaking, Nordic and Western European countries. Parents reported higher meaning in life in all countries, and this did not vary greatly from region to region.

Figure 4. Effect of children in the home on life satisfaction and meaning in life by country cluster. Israel was not included in these analyses because it could not be grouped into any of the country clusters.

This research shows that having children in the home tends to be associated with less life satisfaction for women than men overall, particularly for single mothers. There was some variation in this among country clusters, with the Nordic countries showing the highest life satisfaction for mothers. This is likely related to greater state support of parents in those countries, including mandatory long and well-paid parental leaves.

Yet in all countries, for both men and women, having children in the home was associated with greater meaning in life—and this was true across all age categories, education levels, and partnership statuses. Life with children may be more stressful and perhaps less satisfactory, especially for younger parents, the poorly educated, and the unpartnered, but it is more meaningful overall. For modern Europeans raising children, it seems, life is not meaningless as Nietzsche and others have suggested but rather full of the kind of meaning that comes from giving to others, as suggested by Tolstoy and Dylan.

Rosemary L. Hopcroft is Professor Emerita of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She is the author of Evolution and Gender: Why it matters for contemporary life (Routledge 2016), editor of The Oxford Handbook of Evolution, Biology, & Society (Oxford, 2018), and author (with Martin Fieder and Susanne Huber) of Not So Weird After All: The Changing Relationship Between Status and Fertility (Routledge, 2024).

*Photo credit: Shutterstock