Highlights

- Benefits of home ownership include enhanced life satisfaction and psychological health, lower exposure to crime, higher rates of civic involvement, and better school performance. Post This

- The satisfaction, stability, freedom, and control that come from owning a home are also natural results of having ownership of education, employment, healthcare, and retirement savings. Post This

- Our failure to make ownership achievable for our younger generations is more than an economic crisis: it has ramifications for the well-being of children, families, and communities. Post This

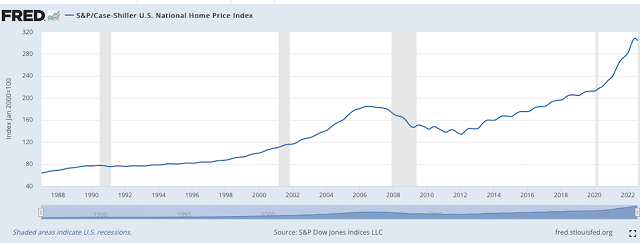

Since 1987, the S&P/Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price Index has measured the (very complex weighted) average price of homes in the United States. Since 2012, the index has more than doubled, and the beginning of COVID kicked off a period of unprecedented acceleration, reaching a peak in June of this year, and only declining very slightly from the peak since then.

Source: FRED, St. Louis Fed

These economic measurements have real implications for real people: in particular, that it’s difficult to own a home. A recent CNN headline summarized the situation as “Millennials have almost no chance of being able to afford a house.”

Unaffordable housing is bad news for many reasons, and not all of them are purely economic. A study by the U.S. Census Bureau found that high housing costs and low home ownership rates were negatively associated with marriage rates. A peer-reviewed study found that expensive housing markets can delay a woman’s first birth by three to four years, presumably because couples wish to have economic security and achieve home ownership before they take the big step of starting a family.

The effects of home ownership on family life don’t stop there. Two professors from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill documented a variety of social benefits of homeownership. These benefits include enhanced life satisfaction and psychological health, lower exposure to crime, higher rates of civic involvement, and better school performance among children who benefited from greater residential stability.

Owning a home can clearly help families and children. But it’s not the only type of ownership that can be beneficial. The satisfaction, stability, quality, freedom, and control that come from owning a home are also natural results of having ownership of other important aspects of life, including education, employment, healthcare, and retirement savings.

Take employment as an example. Owning a business is a socially valuable type of ownership, analogous to homeownership. The self-employed, whether they own a small or large business, own their work hours and their income streams, and can’t be tossed overnight into penury at the whim of a single employer. They also aren’t subject to employment contracts that limit their speech and expression. This gives them autonomy and means they can’t be as easily intimidated or bribed by plutocrats or the political class. Operating a business usually means being involved in a community and gives owners an interest in investing in the community so it can continue to thrive. The same stake, stability, and control that homeownership provides to people and families can come from self-employment, though only a small minority of Americans enjoy it today.

Pursuing broad-based ownership of homes and other essentials as a policy goal is not a new idea. You may remember that at the beginning of this century, the Bush administration frequently invoked an ideal of an “ownership society,” advocating personal ownership of homes, retirement savings accounts, medical decision-making rights, and more. President Bush justified the ideal of broad-based ownership as follows: “The more ownership there is in America, the more vitality there is in America, and the more people have a vital stake in the future of this country.”

Much of the social science research demonstrating the social benefits of ownership had not been done at the time of President Bush’s speech, but the idea is exactly right: a vital stake in the future through ownership is something that benefits individuals and their children.

Before Bush, the same goals were pursued vigorously by British conservatives, including Margaret Thatcher, who created a way for 1.5 million public housing tenants to purchase their housing units, become homeowners, and gain the benefits of ownership for themselves and their families.

The dream of an ownership society is older than Thatcher’s administration. In 1911, G.K. Chesterton described family ownership of income-generating property as not only one policy goal among many, but the only proper criterion by which to judge a government:

An honest man falls in love with an honest woman; he wishes, therefore, to marry her, to be the father of her children, to secure her and himself. All systems of government should be tested by whether he can do this. If any system, feudal, servile, or barbaric, does, in fact, give him so large a cabbage-field that he can do it, there is the essence of liberty and justice. If any system, Republican, mercantile, or Eugenist, does, in fact, give him so small a salary that he can’t do it, there is the essence of eternal tyranny and shame.1

In Chesterton’s more agrarian age, owning a large enough cabbage field was enough to provide both a home and self-employment to a young couple. In other writings, he and other thinkers described an ideal society in which each family could own “three acres and a cow,” which would enable families to provide for themselves, get a stake in a community and society, and gain all the direct and indirect benefits of ownership. In our own day, ownership of homes and small businesses is more complicated and less dependent on agriculture, but the goal of broad-based small-scale ownership of homes and family businesses is still a worthy one.

Nor was Chesterton the first to have the idea of society-wide small-scale ownership. An ancient Biblical prophecy describes ideal property ownership arrangements as “sit[ting] under” your “own vine” and your “own fig tree” without fear.2

Ancient prophets didn’t dream of mere luxury, or technological progress, or abundance alone. They didn’t describe the ideal personal outcome as being a middle-manager assistant vice president of a multinational vine and fig tree conglomerate. Nor did they promise that every person would have millions of fig trees or dependent employees to cultivate them. Instead, they described the ideal far-future arrangement of a perfect society as based on sustainable small-scale ownership of what it took to support a modest but flourishing life (one’s “own fig tree” for “everyone”), unmolested by rapacious bandits or states. Without the benefit of the social science and economic studies of the next several thousand years, they already knew that broad, small-scale ownership of resources, including one’s own place to live and one’s own family-run business, was the best arrangement for individuals and families.

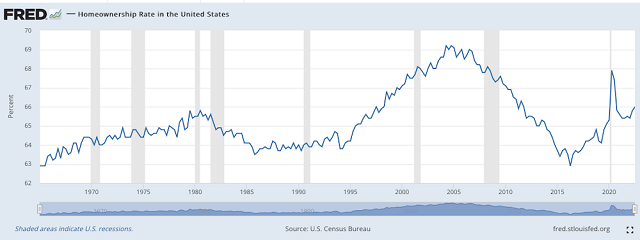

We have not yet achieved that ideal ownership society. Homeownership rates have not changed much in the last 50 years, mostly fluctuating between around 62% and 70%:

Source: FRED, St. Louis Fed

Outside of homeownership, the news is arguably worse. For example, in 2015, only about 10% of workers in the U.S. were self-employed. Since self-employment is today’s equivalent of owning the income-generating cabbage field, it seems that we’ve failed the ancient test of a just society.

The recognition that broad-based, small-scale home and resource ownership benefits families is ancient. But even though we’ve had hundreds of years to try to bring it about, it’s never been fully achieved for everyone. For many, home ownership is a lifelong dream, and recent housing cost increases have been described as “the American dream slipping away.” Our failure to make ownership achievable for younger generations is more than an economic crisis: it has ramifications for the well-being of children, families, and communities that will ripple through the next decades. For those who want to provide support for the formation of strong, healthy families and communities, making our society an ownership society should be near the top of our list of goals.

Bradford Tuckfield is a data science consultant. His latest book is Dive Into Algorithms.

1. G.K. Chesterton, The Illustrated London News, 25 March 1911

2. Micah 4:4 (Old Testament, New International Version)