Highlights

- A substantial number of individuals reported that they experienced improved family relationships as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Post This

- When relationships grow during adversity, there can often be a stronger sense that “we did that, we got through this,” and that sense of resilience can be very beneficial. Post This

- A cohesive family mindset creates a home in which the sacrifices necessary for the good of the family are not a barrier to one’s happiness but rather another means to realize happiness. Post This

The COVID-19 pandemic was a challenging time that negatively affected the lives of many individuals and families. But were its effects negative for all families? As decades of resilience research has taught us, some people adapt positively, even making gains, during times of significant hardship. In that frame, did some families maintain their level of well-being, or even experience improvements in it, as a result of the pandemic? If so, what factors differentiated families that became worse, better, or remained the same? A recent study by Noah Larsen, Qiujie Gong, and the two of us sought to answer such questions.

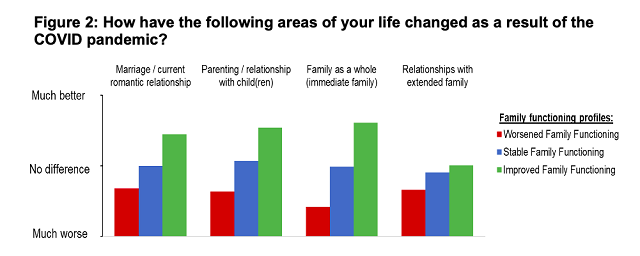

In September of 2022, approximately two and half years after the onset of the pandemic, we surveyed a nationwide sample of nearly 600 adults living in the United States. As part of this study, we asked individuals how aspects of their family life had changed as a result of the pandemic. Individuals answered this question with respect to changes in their marriage (or current romantic relationship), in their relationship with their child(ren), in their immediate family as a whole (those they live with), and in their relationships with extended family.

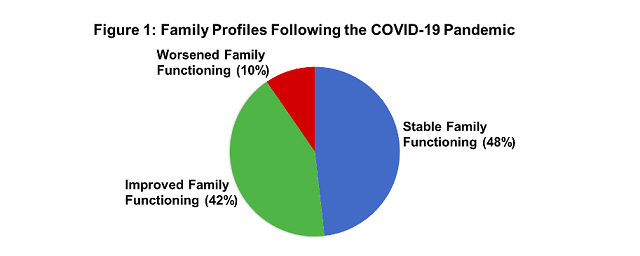

We then identified groups (or latent profiles) of families based on individuals’ responses to these four questions. Figures 1 and 2 display our results.

As Figure 1 shows, we found three distinct family profiles, which were classified as worsened family functioning (10% of sample), stable family functioning (48% of sample), and improved family functioning (42% of sample). As shown in Figure 2, individuals in the worsened family functioning reported the lowest levels on these COVID-related questions, with average response levels indicative of being “somewhat worse” on all four questions.

In contrast, individuals in the stable family functioning group had average response levels on each of the four questions indicative of “no difference/remained the same.” Individuals in the improved family functioning group had average response values that indicated “somewhat better” change as a result of the COVID pandemic for marriage, parenting, and immediate family relationships; responses for relationships with extended family remained at the midpoint on this scale (i.e., no difference/remained the same) for this group.

These results highlight that a substantial number of individuals reported that they did, in fact, experience improved family relationships—at least within the immediate family—as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. It may seem surprising that only 10% reported worsened family functioning as a result of the pandemic. We were surprised at the robust percentage who say things got better.

This finding has some parallel with a report on how the Great Recession of the early 2000’s affected marriages and individuals’ marital commitment. In that study, more than half of the respondents reported that the recession had strained their marriage, but, still, 58% reported the deepening of commitment to their marriage. We believe that when relationships grow during adversity, there can often be a stronger sense that “we did that, we got through this,” and that sense of resilience can be very beneficial. Years earlier, Catherine Cohan and Steve Cole studied changes in family life resulting from hurricane Hugo in 1990. Using data on changes in marriage, divorce, and birth, they found that in the face of such adversity, marriages, births, and divorce all increased. They interpreted their findings to mean that, in the face of life-threatening events, people were generally led to make decisions that altered their life course.

The interesting question in all this is which relationships, marriages, and families improve, and which ones decline during trying times? The second aim of our study sought to help answer such a question by identifying factors that differentiated the three family profiles identified in Figure 1.

For this, we investigated group differences across a set of 11 different variables hypothesized to influence the degree to which stressors affect family relationships. Those variables were:

- Couple Communication

- Couple Social Integration

- Partner Gratitude

- Cohesive Family Mindset

- Perceived Stress

- Financial Hardship

- Loneliness

- Income

- Education

- Marital status

- Gender

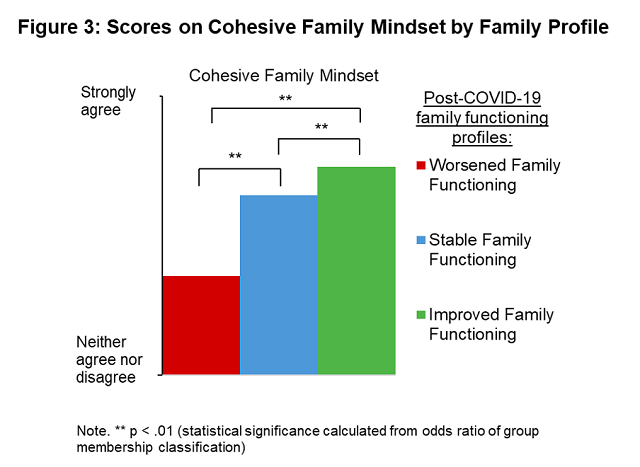

All measures have been utilized in prior research, with the exception of one measure we developed for the current study that assessed what we called a Cohesive Family Mindset. As multiple resilience researchers have described conceptually (but rarely tested empirically), resilient families often possess higher-level meanings, or schemas, of what it means to be a family. Such mindsets provide family members with an orientation to family life that transcends the individual and supersedes each family member’s immediate desires and preferences. It’s getting at “us” and what is required to make the family one desires a reality. The four items we used to assess Cohesive Family Mindset were:

- Our family has a strong sense of being a team

- As a family, we are on the same page with a lot of things

- It makes me happy to make other people in my family happy

- My family is worth the investment and sacrifice it requires

Returning to our second question—how were individuals in these family profiles different across these 11 variables? Somewhat to our surprise, only one variable significantly differentiated all three groups. That variable? Our newly developed measure of cohesive family mindset. As Figure 3 illustrates, individuals in the improved family functioning group following the pandemic reported a higher score on this construct compared to individuals in the stable and worsened family functioning profiles (i.e., had the most amount of agreement with the Cohesive Family Mindset items). Additionally, individuals in the worsened family functioning profile reported a lower score on this measure compared to individuals in the other two family profiles (i.e., had the least amount of agreement with the Cohesive Family Mindset items).

What is our main takeaway from this second set of findings? For that, we’ll quote from a piece by Scott from 2009:

As a field, I think social science has missed something when it comes to measuring things that are important about families. Marital happiness is, to be sure, important. (But) there is a different, maybe deeper, kind of happiness that some people experience in life…like a contentment that a couple can experience (but might not experience) from building a family together.

During times of adversity and hardship, orientations to family life that emphasize teamwork and personal fulfillment through meeting the needs and wants of the broader family unit—versus fulfillment through meeting the needs and wants of oneself—may provide a unique strength-based asset for families. In this way, as an individual adopts a more cohesive family mindset, personal desires find alignment (and not opposition) to familial investments.

Theoretically, we believe that a cohesive family mindset creates a home in which the sacrifices necessary for the good of the family are not a barrier to one’s happiness but rather another means by which happiness can be realized. And in doing so, family relationships can grow stronger, even in the midst of trying times.

Allen W. Barton is an Assistant Professor & Extension Specialist in the Department of Human Development & Family Studies at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Scott M. Stanley is a research professor at the University of Denver and a senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies (@DecideOrSlide).