Highlights

- There is a proven path for success. That pathway runs through America’s three core institutions: education, work, and marriage. Post This

- The success sequence offers a way out of poverty for young adults who have grown up in non-intact families. Among Millennials who didn't grow up with both biological parents but followed all three steps of the success sequence, 95% are not poor as adults. Post This

- The vast majority of black (96%) and Hispanic (97%) Millennials who followed this sequence are not poor in their mid-30s (ages 32 to 38). Post This

Editor's Note: The following is excerpted from "The Power of the Success Sequence for Disadvantaged Young Adults," a new report from the Institute for Family Studies and American Enterprise Institute that is being released today at AEI.

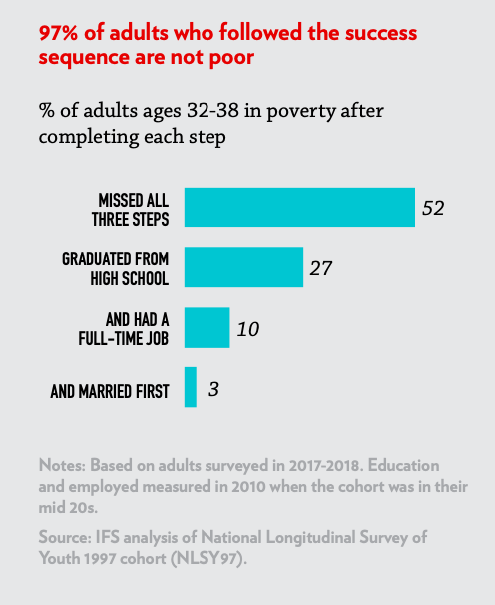

The “Success Sequence,” a formula to help young adults succeed in America, has been discussed widely in recent years, including by Brookings Institution scholars Ron Haskins and Isabel Sawhill. The formula involves three steps: get at least a high school education, work full time, and marry before having children. Among Millennials who followed this sequence, 97% are not poor when they reach adulthood. The link remains strong when this cohort of young Americans reaches their mid-30s, according to a new IFS analysis of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY).1

The success sequence seems like common sense. In an interview, Nobel Laureate James Heckman called the success sequence a fact, adding: “When children or young adults have a child out of wedlock and if they take responsibility for that child—even if they don’t—that’s going to generally impair their progress.” Similarly, Bryan Caplan commented that the causation between the success sequence and poverty is obvious: “‘Dropping out, idleness, and single parenthood make you poor’ is on par with ‘burning money makes you poor.’ The demand for further proof of the obvious is a thinly-veiled veto of unpalatable truths.”

Critics of the success sequence often point out that it ignores the “obstacles individual efforts can’t always overcome.”There is no question that structural disadvantages make it more difficult to follow the three steps of the sequence. But that is also why it matters: Young adults who manage to follow the sequence— even in the face of disadvantages—are much more likely to forge a path to a better life.

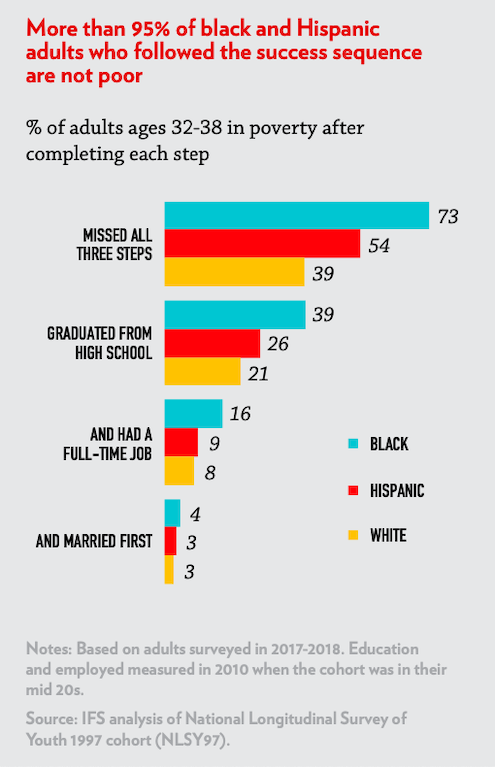

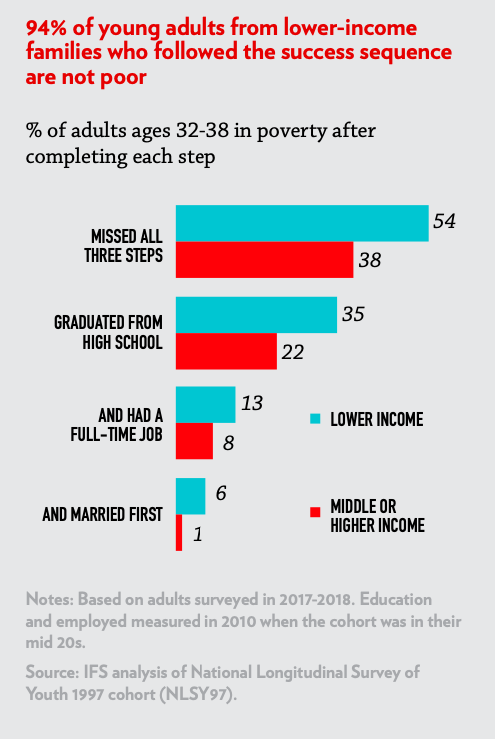

In fact, young adults from disadvantaged circumstances who follow the sequence are markedly more likely to overcome challenges and achieve economic success. The vast majority of black (96%) and Hispanic (97%) Millennials who followed this sequence are not poor in their mid-30s (ages 32 to 38), as is also the case for 94% of Millennials who grew up in lower-income families and 95% of those who grew up in non-intact families. Moreover, for those who do not have a college degree but only finished high school and who work and marry before having children, 95% are not poor by their mid-30s.2

Not only does following the success sequence help young adults in adverse circumstances avoid poverty, but those who manage to stay on the sequence are forging a path to move up to the middle class and realize the American Dream. By their mid-30s, 80% of black young adults and 86% of Hispanics who have followed all three steps are in the middle- or higher-income bracket, compared with 91% of whites. The shares are similar among young adults who grew up in lower-income families (82%) and those who did not grow up with both parents (84%). Even though racial gaps in achieving middle class status still exist after following the success sequence, as Richard Reeves observed in cross-sectional data, the vast majority of black and Hispanic young adults are in the middle class or higher today after completing all three success sequence steps.

This report focuses on how structural factors (e.g., race/ethnicity, family income growing up) are linked to the success sequence for Millennials. We also looked at the role of high school graduation in the success sequence steps. Poverty is the main economic outcome used in this report. All analyses are based on data from NLSY97 Round 18 (conducted in 2017 and 2018) when these young adults were ages 32-38.3

Here is a detailed rundown of the results:

Race/Ethnicity

Missing success sequence steps in life is clearly linked to more poverty, especially for black and Hispanic adults.4 For black Millennials without a high school education or a full-time job by their mid-20s, who also didn’t follow the marrying-before -having-children route, 73% are in poverty at ages 32 to 38. For Hispanic Millennials who missed all three steps, 54% are in poverty by their mid-30s. The share among whites is lower, about 40% who missed all three steps end up being in poverty. In a way, this shows that racial minorities, especially blacks, face stronger structural barriers to moving up.

The encouraging news is that with completion of each step of the success sequence, the racial gap narrows rapidly. For Millennials who followed all three steps, only 4% of blacks and 3% of Hispanics are poor by their mid-30s. Stunningly, the racial gaps in poverty are almost closed.

Black boys face a lot of challenges in America: even black boys from wealthier families still earn less in adulthood than white boys who grew up in similar backgrounds. According to a study by Harvard economists Raj Chetty and colleagues, black boys raised in top-income households are more likely to become poor than to stay in top-income brackets as adults. However, for black boys who followed the success sequence, 93% are not poor and 78% make it to the middle- or higher-income bracket as adults.

Family Background

Low-income young adults who followed the success sequence also do markedly better. After following all three steps, 94% of Millennials who grew up in the bottom third of the income distribution are not poor by their mid-30s.

Similarly, the success sequence offers a way out of poverty for young adults who have grown up in non-intact families. Among Millennials who didn't grow up with both biological parents but followed all three steps of the success sequence, 95% are not poor as adults (see more details in the Appendix in the full report).

Again, the poverty gap between young adults from disadvantaged backgrounds and others is the largest among those who missed all three success sequence steps. Among young adults from lower-income families who missed all three steps, 54% end up in poverty. The share is only 38% among young adults from middle- or higher-income families. With each completed step, the gap is shrinking. For those who completed all three steps, family background matters the least: Only 6% of Millennials from lower-income backgrounds are poor as adults, compared with 1% of their peers from families in the middle- or higher-income bracket.

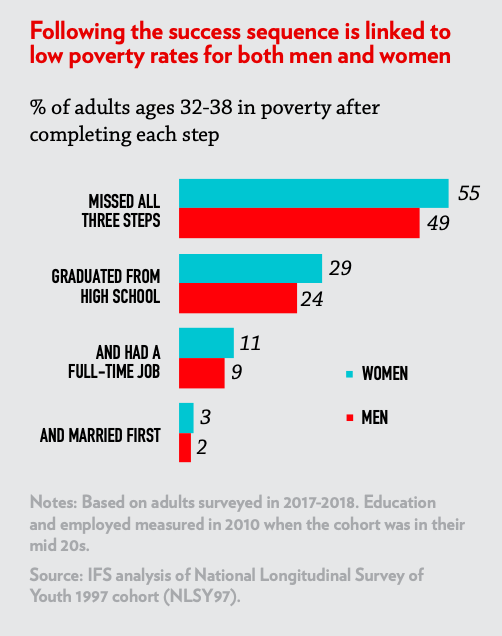

Gender

Overall, women are more likely than men to be in poverty. Among Millennials ages 32-38, 15% of women are in poverty, compared with 12% of men. Among Millennial woman who missed all the success sequence steps, 55% are in poverty; the share is lower among men who missed all three steps (49%).

Finishing high school and getting a full-time job by their mid-20s helps both genders conquer poverty. And for Millennial women who also put marriage before the baby carriage, 97% are not poor by their mid-30s. The gender gap is almost nonexistent.

It is intriguing to see that among Millennials who completed (at least) a high school education and have a full-time job but are unmarried and childless—the so called “on-track” group—there is a bigger gender gap. It is Millennial men who are more likely to be in poverty. About 6% of unmarried and childless Millennial men who have completed the education and work steps are poor by their mid-30s, compared with only 2% of women in the same situation.

College Is Not a Necessity for Success

Compared with Boomers and Gen Xers, Millennials are much better educated. Nearly 40% of Millennials ages 25 and older have at least a bachelor’s degree; the share among Gen Xers and Boomers is under 30 percent. For the sample in NLSY97, 30% were college-educated by age 25, and 55% only finished high school.

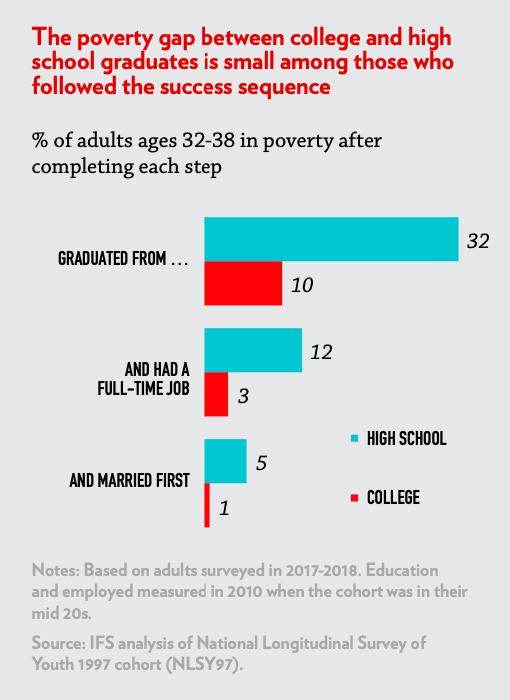

Even though having a college degree is associated with many benefits in life, Millennials who complete the success sequence but only have a high school education have a much lower risk of poverty as adults. Fully 95% of high school educated Millennials who completed the success sequence are not poor by the time they are in their 30s.5

Moreover, 82% of Millennials who completed the success sequence but didn’t pursue a college degree are in the middle or higher-income bracket by the time they are in their 30s. For those who completed all the success sequence steps and had a college or higher degree, 96% are in the middle or higher tier of income distribution by their mid-30s.

To sum up, young adults from disadvantaged backgrounds who follow the success sequence are much more likely to forge a path towards the American Dream than their peers who did not manage to follow the sequence. Despite structural barriers during childhood, whether these barriers are related to race, income, or family instability, taking these three steps—finishing high school, getting a full-time job, and getting married before having children—is associated with a much lower risk of poverty when reaching adulthood. Furthermore, the association between the success sequence and poverty is robust after controlling for a range of factors including race/ethnicity, family income, family structure, AFQT test scores, and education. Specifically, the odds of being poor in your mid-30s are 11 times higher for young adults who did not complete the success sequence versus those who did.

Given the overwhelming evidence that the success sequence is linked to better economic outcomes for young adults, it is time to help young adults follow the steps. This is especially critical for young adults from less-advantaged backgrounds who often lack access to the resources that make the steps easier to take. These young adults need quality schooling, better job opportunities, and resources and guidance to help them navigate relationships. As we suggested in our earlier report, policymakers, educators, and civic and business leaders should move to make each component of the success sequence more accessible. This will require new public and private policies and initiatives. For example, schools should do much more to serve adolescents who are not on the college track—helping students achieve occupational and employable skills. As this report indicates, college education is not required for success. For young adults who do not have a four-year college degree (which is the majority of young adults today), vocational education and apprenticeships are viable alternatives to accessing quality careers.

We should start sharing the success sequence message with those who need it the most. We need to teach the success sequence in schools and launch campaigns that promote the success sequence to high school students across the country—including to students from poor and working-class communities. A recent study by Nat Malkus at the American Enterprise Institute suggests that the success sequence is quite popular among parents as well as the American public. More than three-quarters of American parents (76%) say they favor teaching it in public schools. The support is broad-based among the public: more than 70% of Democrats and 85% of Republicans favor teaching students the success sequence, as do 68% of black Americans, 74% of Hispanic Americans, and 72% of those adults who did not follow the success sequence themselves.

The COVID-19 pandemic has upended the lives and prospects of countless young adults across the country. While we should talk about racism and the structural barriers facing all too many young adults, we also need to underline the truth that despite these barriers, there is a proven path for success. That pathway runs through America’s three core institutions: education, work, and marriage. Using James Heckman’s words about teaching the success sequence: “If you didn’t teach it, you’d really be remiss.”

Download the full IFS/AEI report, which contains additional charts and tables. Learn more about the success sequence here.

1. The cohort interviewed in NLSY 97 was born between 1980 and 1984 and is considered the oldest group of Millennials. “Young adults” and “Millennials” are used interchangeably in this report.

2. In this analysis, finishing high school and having a full-time job (working 35+ hours per week and 50+weeks a year) were measured when respondents were in their mid-20s.

3. This is an update from the analysis in The Millennial Success Sequence report published in 2017. The two reports share a similar methodology.

4. Results for Asian Millennials are not reported because of small sample size (n<100).

5. Millennials with only a high school education are those whose education level was high school at their mid-30s.