Highlights

- Nordic welfare states help parents, including most mothers, work. And then they send parents a large bill. Post This

- Since the 2008 recession, Nordic fertility rates have fallen rather steeply, and in sociologically homogenous ways, most rapidly in Finland. Post This

- What we thought we knew about the Nordic model of high fertility clearly needs to be revised. Even what we thought we knew about the role of gender-egalitarian attitudes in increasing fertility may now be invalid or incomplete. Post This

Around most of the world, low fertility has become an urgent challenge for policymakers. This is the case even in the Nordic societies, which—until not so long ago—were widely seen as a policy model to be adopted by other countries aiming to increase fertility levels. What is happening? And what might be done?

In a study in Royal Society Open Science, demographer Robert Gal, sociologist Marton Medgyesi, and I suggest that any comprehensive answer requires us to shine a broader light on all the resources it really takes to raise a newborn all the way to productive adulthood today. Parents must use a combination of three different resource channels to rear children:

- Channel 1: working and paying higher net public transfers (or “taxes”) that will finance state activities, including social policies for children

- Channel 2: staying at home to care for their child (giving “time”)

- Channel 3: buying market goods and services (giving “money”)

The need for large resources (a high transfer load) to rear children to adulthood remains stable across these three channels—the total transfer load is even remarkably similar across societies as different as Sweden and Taiwan. Switching between these channels does not reduce the parental transfer load. Instead, we show a general logic of transfer conversion between these channels. Parents must do the job, one way or the other: in societies with disappearing three-generational households, most children live under the same roof with only their parents, no longer with other kin or alloparents (such as grandparents).

But importantly, these three channels are not equally visible in statistics. Parents do not keep accounts of how much time and money they spend rearing their children, so these transfers leave few traces. By contrast, taxes and social security contributions (and benefits) are much better recorded in national statistics. We argue that this asymmetric statistical visibility matters a great deal, as it hides an important further asymmetry in who really shoulders the cost of reproducing society.

Shining a Broader Light on All 3 Resource Channels

We use new accounting methods for 12 European Union countries to measure not just all public transfers (the “state”) but also, crucially, the less visible private flows of unpaid household labor and market goods and services. Shining a wider light on these less visible resources reveals to what degree societies tap into a hidden and undervalued world of transfers within families. Better accounting truly shifts perspectives, and not just marginally.

Not surprisingly, we find that parents in Europe contribute somewhat fewer net public transfers than non-parents. After all, it is the primary role of social policies to redistribute along the lifecycle. Much more than they are (cross-class) Robin Hoods, European welfare states are (cross-generational) piggy banks.

But then, away from the statistical limelight, parents (and only parents) additionally provide very large private transfers of time and money to their own children. These hidden extra transfers are so large that they radically change the entire picture. Over an entire working life, the average parental/non-parental contribution ratio in Europe flips around—from 0.73 when measuring net public transfers alone, to 2.66 when including all three transfer types together.

Welfare state benefits are geared mainly towards elderly age groups. Children really do receive a lot of resources in Europe, but these come mainly from their parents, not from the state.

So parents in Europe actually contribute 2.66 times more resources overall than non-parents. It is parents, not taxpayers, who shoulder the largest burden of social reproduction. Even welfare state benefits (channel 1) are geared mainly towards elderly age groups. Children really do receive a lot of resources in Europe, but these come mainly from their parents, not from the state.

This overall 2.66 ratio is the population-weighted average for our 12-country European sample. But the average for our 10-country sample, minus the two Nordic cases, is lower: 2.61. This is noteworthy because our research also reveals another counterintuitive finding: a new ‘Nordic paradox.’

A New Nordic Paradox: Family-friendly Welfare States Implicitly Burden Parents

Perhaps surprisingly, we show that the two highest parental/non-parental contribution ratios in the entire European sample are in the most family-friendly welfare states: Sweden (contribution ratio of 2.99) and Finland (3.17). What is going on here?

Let’s be clear: Nordic welfare states do help parents. But as we argue in our study, they help parents in a specific, narrow, and productivist way. They help parents, including most mothers, work (which is what most mothers in these countries want). And then they send parents a large bill. The help is real—but it is not a gift.

Let’s take a closer look at the three childrearing resource channels to understand this Nordic paradox. Beginning with channel 1— net public transfers (or taxes contributed minus benefits received). Remember that welfare states are transfer-and-tax machines. Nordic working mothers and fathers really do get more benefits from their welfare states—the transfer arm of the machine. But they also pay the same high levels of income taxes and social security contributions as Nordic non-parents pay—and higher levels than parents pay in most of the rest of Europe—the tax arm. The same is true for the high Nordic taxes on consumption goods, including those levied on food, clothes, heating, and toys for children (channel 3).

Take channel 2—time transfers. True, Nordic parents get a longer time off to care for young children in the early months of children’s lives than in many other rich countries. But while the benefit of that time goes to children, the replacement cost of the time is higher than elsewhere. Nordic societies notoriously have more strongly compressed wage distributions. This means that many low-end service sector professions tend to earn more than elsewhere. Hence the replacement cost of parental time (the wages of professional carers such as nannies and daycare providers) is higher, too. For the same reason, when Nordic parents want to hire a babysitter or other private child care services, they really must pay more in the market than what German or French parents must pay for the same service (channel 3).

Then, when Nordic parents go back to work after comparatively long and generous parental leaves, they send their children to the notoriously well-subsidized public day care centers and later to public schools and universities. But, through their taxes, parents must help finance the public sector wages of the carers, kindergarten and school teachers, and university staff. And in these large, service sector-heavy Nordic welfare states, public sector carer wages really are higher than elsewhere in Europe. We’re back to channel 1.

Source: UN Population Division. World Population Prospects: 2022 Revision; Statistical databases and publications from national statistical offices; Eurostat: Demographic Statistics

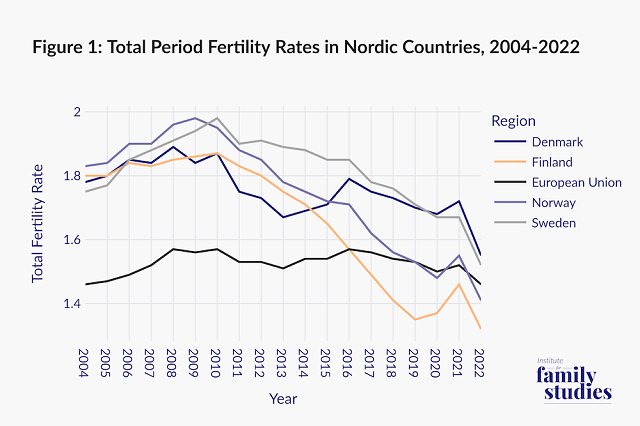

Our new findings from 2010 data become particularly relevant in light of the marked decline of Nordic fertility rates subsequently (Figure 1). As demographer Anna Rotkirch and others have noted, Nordic countries actually boasted higher fertility rates than the EU average around the time of the great recession of 2008. Nordic policies were widely seen as a model to be adopted elsewhere for raising fertility rates. But since the 2008 recession, Nordic fertility rates have fallen rather steeply and in sociologically homogenous ways, most rapidly in Finland. By 2022, Finland and Sweden were below the EU average.

Today, childlessness levels in the Nordics are on the rise, and they are the main cause of declining total period fertility levels. Which means these are not merely childbirth postponement effects. It is mainly first births, not second or higher-order births, that are declining fastest in the Nordics, especially among lower socio-economic status groups; those groups for whom the particularly high total parental transfer burden might most strongly disincentivize fertility.

Valuing Reproduction Better: What it Takes for a Welfare State to be Really Family-friendly

Our work on the three channels needed to raise children to adulthood may shed some light on these Nordic developments more generally. Even welfare states like Sweden or Finland that provide more cash in family benefits, a few more weeks in parental leave, and better child care and kindergarten facilities that other welfare states—they, too, fiddle at the margins. They are indeed generous to parents, but only in one-half (state benefits, not taxes) of the altogether three resource channels it really takes to raise a newborn to productive adulthood. And even this state benefit generosity toward the young is relative: all European countries, including the Nordics, have pro-elderly welfare states, within child-oriented societies.

It is the statistical invisibility of the substantial time and money transfers involved in childrearing that makes the full parenting efforts fly under the radar of politicians and policymakers. It is this invisibility that allows welfare states to free ride on the cost of producing the next generation of workers and taxpayers. Care economist Nancy Folbre, political theorist Nancy Fraser, and many others have pointed out that societies value production but free ride on the contributions (of parents) toward social reproduction. Anna Rotkirch asks aptly: “what would society look like if we valued reproduction, and raising babies, not just your own, as much as [economic] production?”

Nordic welfare states help parents, including most mothers, work (which is what most mothers in these countries want). And then they send parents a large bill. The help is real, but it is not a gift.

Of course, declining fertility in contemporary societies is a complex macro-social problem. It has a whole host of causes that need to be tackled by more holistic policies that understand the wider culture and the contemporary sociology of family formation. For decades, the problem was relatively stable, if intractable, across rich societies: people consistently claimed they wanted more children (two) than they actually have in practice. But in recent years, new sociological norms appear to be arising among younger generations. Arnstein Aassve et al. suggest that while family may remain normatively important in today’s low-fertility culture, ideal family size may now be much lower (one child). Many young people today, because of environmental and global-political worries, rising labor market and life course insecurity, and perhaps new fragilities and anxieties are ever more tempted to remain DINKs (double income, no kids).

Un-taxing the Stork in Low-fertility Societies

Our findings on the full transfer cost of rearing children in turn shed light on two other key factors: (1) what our societal models implicitly value and do not value, and (2) what our policy models do wrong—even when they think they do things right. As long as even family-friendly societies mainly fiddle at the margins, they adhere to an erroneous stork theory of how new adults come about. This will not solve the larger, deeper sociological and cultural causes behind declining, stubborn-low, or lowest-low fertility levels—including cohort fertility.

What we thought we knew about the Nordic model of high fertility—including the policy lessons to be drawn—clearly needs to be revised. Even what we thought we knew about the role of gender-egalitarian attitudes in increasing fertility may now be invalid or incomplete.

Our research shows that while Nordic policy models do a lot on the state benefits side (half of channel 1), they do not fully value what parents really contribute in the other two-and-a-half resource channels. In Folbre’s words: they unwittingly tax the stork.

Shining a wider light on the invisible value production of families, and then actually valuing reproductive contributions much more fully, is a one big step in the direction of at least partly reversing decreasing fertility trends. In Nordic Europe as in other low-fertility societies, we need to start valuing and stop taxing reproduction.

Pieter Vanhuysse (PhD, LSE) is a member of the European Academy, a Full Professor of Political Economy and Public Policy at the Department of Political Science and a Chair at the Danish Institute for Advanced Study, University of Southern Denmark. He works on political economy, welfare states, political demography and intergenerational transfers.