Highlights

Amid all the changing family structures we’re seeing in the U.S. today, middle-class immigrants arguably paint one of the more familiar icons of a traditional ideal, at least on their statistical face. Asian Americans are more likely than the average American to get and stay married; just 5 percent of Asian-American adults are divorced, versus 10 percent of the general population. Eighty-three percent of Asian kids live in two-parent homes. Hispanics, while marrying less than the population at large, also split up less frequently than the general population (8 percent of them are divorced).

So many variables, caveats, and accelerating change accompany these numbers, it’s almost foolish to try to name anything culturally distinctive in people’s marital ecosystems that might contribute to the more enduring unions among us. But a robust and nuanced report authored last year by sociologist Zhenchao Qian and referenced by Anna Sutherland on this blog grants credence to the idea that for America’s newer citizens, there may be more powerful norms shaping marital patterns than the educational and economic factors now predictive for those born in the U.S.

According to Qian’s research, immigrants with lower levels of education are still marrying at roughly similar rates to those with higher-level degrees, a gap much narrower than that experienced by their U.S.-born counterparts. Similarly (and relatedly), while economic resource “is the key to marriage among the U.S. born,” less educated and racial-ethnic minorities are marrying at similar levels to their highly educated and white counterparts. “Immigrants marry regardless of economic resource,” Qian concludes.

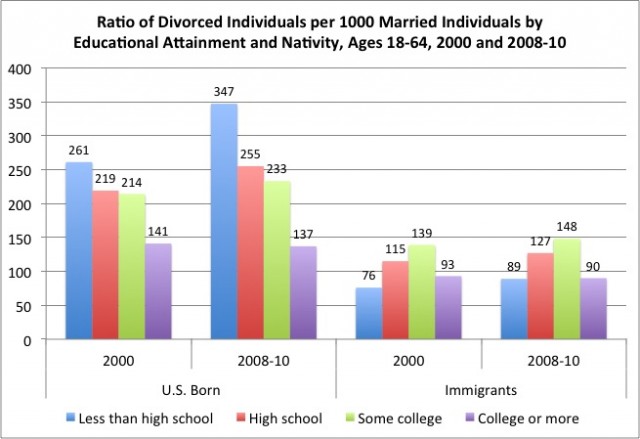

It is relatively widely known that immigrants, regardless of national origin, divorce less than their U.S. born counterparts. Yet Qian’s probe into the relationship between marital stability and education uncovers an interesting fact: Immigrants actually divorce more the more highly educated they are, except for those with college degrees. In other words, the relationship for immigrants is an inverted U: Those with less than a high school education and those with completed college education have the lowest divorce rates.

These are just highlights from the statistics of a nation now filled with all sorts of couples and ethnicities from around the world. But the central finding from Qian’s report – that neither education nor economics matter as much for immigrant family structures as they do for the U.S.-born – raises a number of questions. What is going on within the value systems of the ever-morphing populations behind these numbers? If neither education nor economics are determining the likely contours of an immigrant’s marital path, what else is in the water of the communities that are shaping these outcomes? Is it religion? Multi-generational living arrangements? More familial involvement in choice of spouse? A keener awareness and valuing of the witnesses to one’s marriage? Other social support structures originally created to help with the challenges of the immigrant experience itself? Could the native-born, whose marriage trajectories are now correlated most closely with education and economics, learn something from the values and norms that hold a higher weight in other countries?

The answer to this curiosity is too huge and complex for the scope of this post, so instead I thought I’d create a list of questions for sociologists and journalists to consider as they peer more deeply into the why’s that undergird the stats of America’s diversifying family structures, particularly the immigrant stories among us. These questions could be put to individuals within discrete ethnic blocs, a neighborhood, an age bracket of intermarried couples, a gender, a socioeconomic and educational bracket, or some mixture thereof. Here they are, with an invitation for additions:

- Do you consider marriage the first step to adulthood, the last, or something in between? Please rank the qualifiers necessary for assuming official adulthood.

- What is marriage about to you? Romance? Happiness? Companionship? Children? Honoring the past? Existential fulfillment? Pragmatism? Status? Rank these in order of priority, and describe.

- Do you consider the married life to be preferable or superior to the single life?

- If you are married, how have you felt supported in your marriage, and who or what has come alongside you? If you feel isolated in your marriage, why is that? Is what you’ve experienced as a married person in the U.S. different from what your parents experienced in their home country?

- What forces external to your marriage have made your marriage more difficult?

- What were the expectations discussed in your childhood household around marriage? In what ways do you feel you are more American in your approach to your marriage, and in what ways are you patterning yourselves after norms that your parents modeled?

- Whose opinion matters most in the decision to get married? If you met your spouse in the U.S., describe the courtship or dating experience. If there were watching eyes en route to “I do,” where did they come from?

- How were you raised to think about divorce, and what, realistically, would be the reaction of those who matter most to you if you did get divorced?

- What percentage of your friends are divorced? What percentage have never married?

- Do you live with more than two generations in one house? If so, how has your marriage been impacted by this multi-generational living arrangement?

- Describe the relationship with your parents pre-marriage and post-marriage. What sorts of things do you discuss with your parents and what do you keep between you and your spouse?

- Where does the place of the extended family fall next to the nuclear family you have created? Do you live near your families of origin or far away from them?

- If you belong to a religious community, or count yourself religious, how important a role does that community and/or belief system play in your marriage commitment and behavior?

- Do you and your spouse share social networks, allow them to overlap, or engage them separately from one another? Discuss both in-the-flesh circles and online communities.

- Do you and your spouse each have a professional life? If so, describe how you have navigated this dual-working arrangement and whether your respective families understand and/or provided precedent for it.

Anne Snyder is a freelance writer living in Houston, Texas, where she is studying the city’s changing demographics and questions of identity and values therein.