Highlights

- The Marriage Foundation’s new analysis of UK divorces shows that—at least within marriage—men have been behaving progressively better over the last 25 years Post This

- Men who marry today in the UK are “deciders” who really want to get married rather than “sliders” who are doing it under pressure. Post This

In an era of #MeToo, bad behavior by men is quite rightly under the microscope like never before. But it would be wrong to assume that it's only now that something is being done and at last things will improve.

The Marriage Foundation’s new analysis of UK divorces shows that—at least within marriage—men have been behaving progressively better over the last 25 years. To back this up, we commissioned some new data from the UK Office for National Statistics which details the number of divorces, how long the marriages lasted, and whether the husband or wife was granted the divorce.

From this, we can map the number of divorces that have taken place after one year, two years, three years, etc., onto the years when these weddings took place. By doing this every year for all durations of marriage up to 60 years, we can track what happened to the couples who married in any given year going back to 1963.

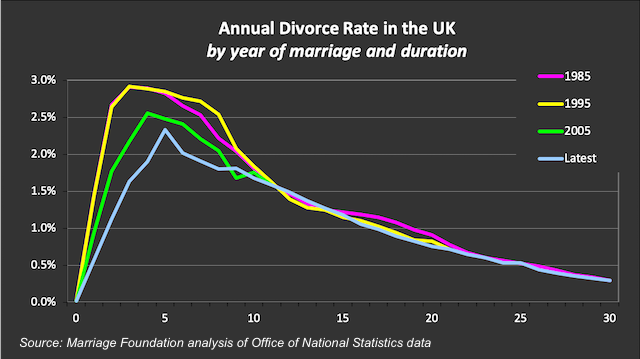

The basic pattern of divorce is always the same (see first chart below).

Whichever year you look at, divorce rates rise in the first few years, peak between years four and eight, and then fall progressively. Clearly long marriages do come to an end. But on average, the risk becomes extremely small after about 30 years.

Where that pattern has changed is almost entirely during the first 10 years of marriage. The four-to-eight year peak in divorce rates rose steadily through the 1970s and 1980s and then fell back again from the 1990s, with the most recent marriages looking much the same as those back in the early 1970s.

So, just as divorce levels rose because more couples were splitting up early on, divorce rates have now fallen because fewer couples split up early on. Once couples get past the first decade of marriage, there has been little to no change in divorce rates, whether couples married in 1975 or 1985 or 1995.

Isn't that amazing? Think of all the social and economic changes since the 1960s. Yet once marriages get past 10 years, their stability becomes highly predictable—on average of course.

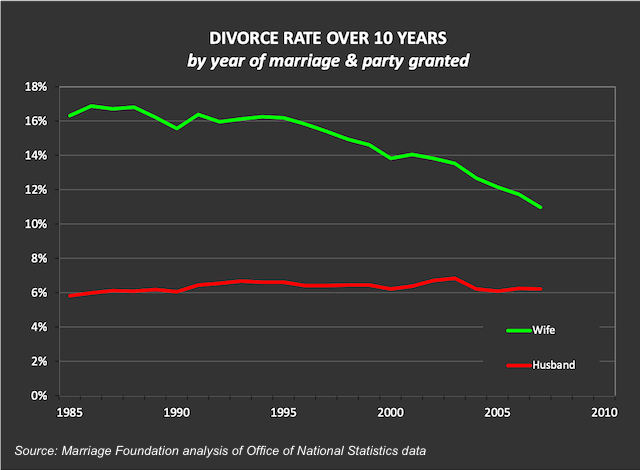

But when we divide divorce rates into whether they are attributable to the husband or the wife—in most cases reflecting who wants the divorce more—the full extraordinary phenomenon appears.

While there has been almost no change in divorces granted to husbands—and don't forget this is about rate and not numbers, so it has nothing to do with fewer marriages—about 80% of the entire fall in divorce is because fewer wives are filing for divorce in their early years of marriage.

This very strong gender effect rules out any kind of economic explanation—such as house prices, or the economy, or cuts, or even changes in women's employment—all of which should affect the desire of both men and women to file for divorce, or not.

There are only two explanations for this. Either men are behaving the same and their wives have become more tolerant—which seems eminently implausible given the current culture—or men are behaving better.

Here's what I think is going on. As social pressure to marry has gradually disappeared, those who do choose to marry are making it more of a deliberate choice. We've already seen evidence from the United States that “deciding,” rather than “sliding,” is particularly important to men's commitment. Well, it looks like we are seeing this in the UK with this gender effect. Divorce rates were higher previously simply because some men were sliding into marriage under pressure from family and friends.

No longer. Men who marry today in the UK are “deciders” who really want to get married rather than “sliders” who are doing it under pressure. Since falling divorce rates are the driving force behind the overall reduction in family breakdown that we've seen in the last five to 10 years, this improvement in men's commitment is having a hugely positive effect. What's more, we expect the fall in breakdown to continue as these stable newly married couples have children who become teenagers.

It used to be thought that cohabiting couples would look more like married couples as marriage became more of an option. In fact, the gap in stability may well be widening.

So, at a time when marriage is becoming stronger because men are behaving better, how do we encourage men who are not married, and whose odds of splitting up are so much worse, to make similar decisions, similar commitments, and hence become more stable?

Harry Benson is Research Director of the UK-based Marriage Foundation.