Highlights

- Parenthood is a "mixed bag" of positive and negative emotions, making the net impact vary depending on how you measure it. Post This

- Overall, after controlling for demographics, parents reported more happiness and meaning and less sadness during their activities, but also more stress and fatigue. Post This

For years now, social scientists have been trying to figure out whether parenthood makes people more or less happy on balance, creating a bunch of conflicting narratives. Maybe kids make us miserable—the finding that tends to get touted in the news the most aggressively. (Sample headlines: “The depressing reason why having kids doesn’t actually make you happier”; “Decades of data suggest parenthood makes people unhappy.”) Or maybe parents used to be less happy than nonparents but they’re not anymore. Or maybe parents are happier, but only after the kids move out. Or maybe parents are just happier, full stop.

The most likely explanation for this confusion is that parenthood is a "mixed bag" of positive and negative emotions, making the net impact vary depending on how you measure it, and a new study from Daniela Veronica Negraia and Jennifer March Augustine goes a long way toward unpacking how this works.

Sometimes parenting is fun, sometimes it's deeply rewarding, sometimes it's stressful, and sometimes it's miserable. Always, it’s tiring. Every parent has known these things since the dawn of time, but sometimes it takes the media and the academic literature a little while to catch up.

The study relies on the American Time Use Survey, which randomly selects U.S. residents to fill out a "time diary" covering a full day of their lives. These diaries contain extensive details about what these people did and when, who else was there, and how they felt subjectively about what they were doing. The big limit, of course, is that each person gives information about a single day, so the survey can't be used to track how people's experiences change after they have kid—it can only be used to compare one group of people with another. In this case, that's parents and nonparents, who, of course, self-select into or out of parenthood and therefore might just be different kinds of people.

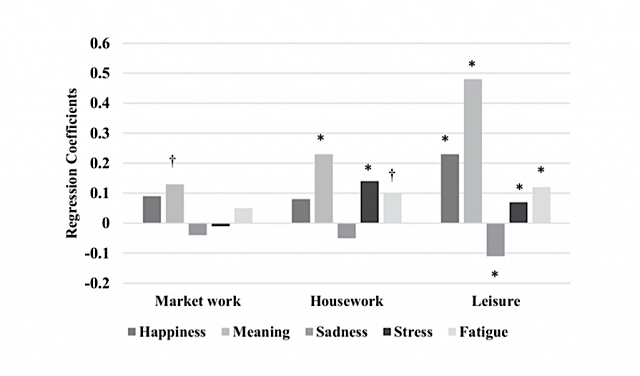

But even with that limit in mind, the results here are fascinating. The authors measure five different types of wellbeing — happiness, meaning, sadness, stress, and fatigue — and track them both overall and during specific activities. Overall, after controlling for demographics (age, race, employment, income, etc.), parents reported more happiness and meaning and less sadness during their activities, but also more stress and fatigue. Notably, though, these answers are given on a scale of 0 to 6, and the differences were always less than half a point (and usually less than a fifth of a point).1

The authors then disaggregate these gaps into different types of activities and also look to see what changes when kids are or are not present. Parents and nonparents are about equally happy when doing paid work, for example, but the gaps observed in the overall analysis were particularly pronounced during leisure.

Source: D. Negraia & J. Augustine, "Unpacking the Parenting Well-Being Gap: The Role of Dynamic

Features of Daily Life across Broader Social Contexts, Social Psychological Quarterly, June 10, 2020.

I initially figured this meant parents were thrilled to get a break from the kids, but it turns out that the gap is driven by leisure activities with the kids. The authors write:

We find that the positive associations between parenting and momentary emotional well-being were driven by the presence of children. . . . When parents were not with their children, parents reported less positive emotions, particularly in all-time . . . and in leisure . . . in which their happiness levels dropped below those for nonparents. We also observed a sharp decline in meaning in all-time . . . leisure . . . and housework. . . . Consistent with this pattern, parents’ significantly lower levels of sadness during all-time . . . and leisure . . . became insignificant during time when they were without their children. At the same time, parents’ greater levels of stress and fatigue compared to nonparents remained relatively unchanged during time when they were without their children, and during leisure, their stress . . . and fatigue . . . intensified.

Sometimes things are made more fun when you get to watch someone else having more fun than you ever could, I guess. (Or maybe parents just feel guilty admitting they were a little bored.) And sometimes when the kids go to bed and you fire up the PlayStation, all you can think about is how tired you are.

In yet another analysis, the authors take into account the age of the respondents’ kids. For some types of well-being, the above patterns are strongest for those with young kids, which probably makes sense, because older kids are a bit more autonomous and affect their parents’ lives less.

It's good that researchers are finally starting to unpack the complicated reality that kids impose on their parents. I have to say again, though, that little of what this paper found will come as a shock to those of us who actually live in that reality. If I hadn't had kids, I'd spend a lot less time cleaning up poop, but I'd also lose the pleasures of baby smiles, toddlers going down slides, and preschool kids slowly figuring out how to read.

The ultimate message of this study is that any decision you make will involve tradeoffs, and, well, that’s life.

Robert VerBruggen is an Institute for Family Studies research fellow and a policy writer for National Review Online.

1. To put it differently, they range from 5 to 11 percent of a standard deviation.